INDIANAPOLIS — Fall may now officially be in our midst, but if you’ve kept up with weather headlines over the law few days, you may have noticed an emphasis on the fact that an El Niño winter is very likely upon us as well.

The climate pattern El Niño began in June and is expected to be strong through the winter and into early spring 2024, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. There is a greater than 95% chance we will experience it through January and March 2024.

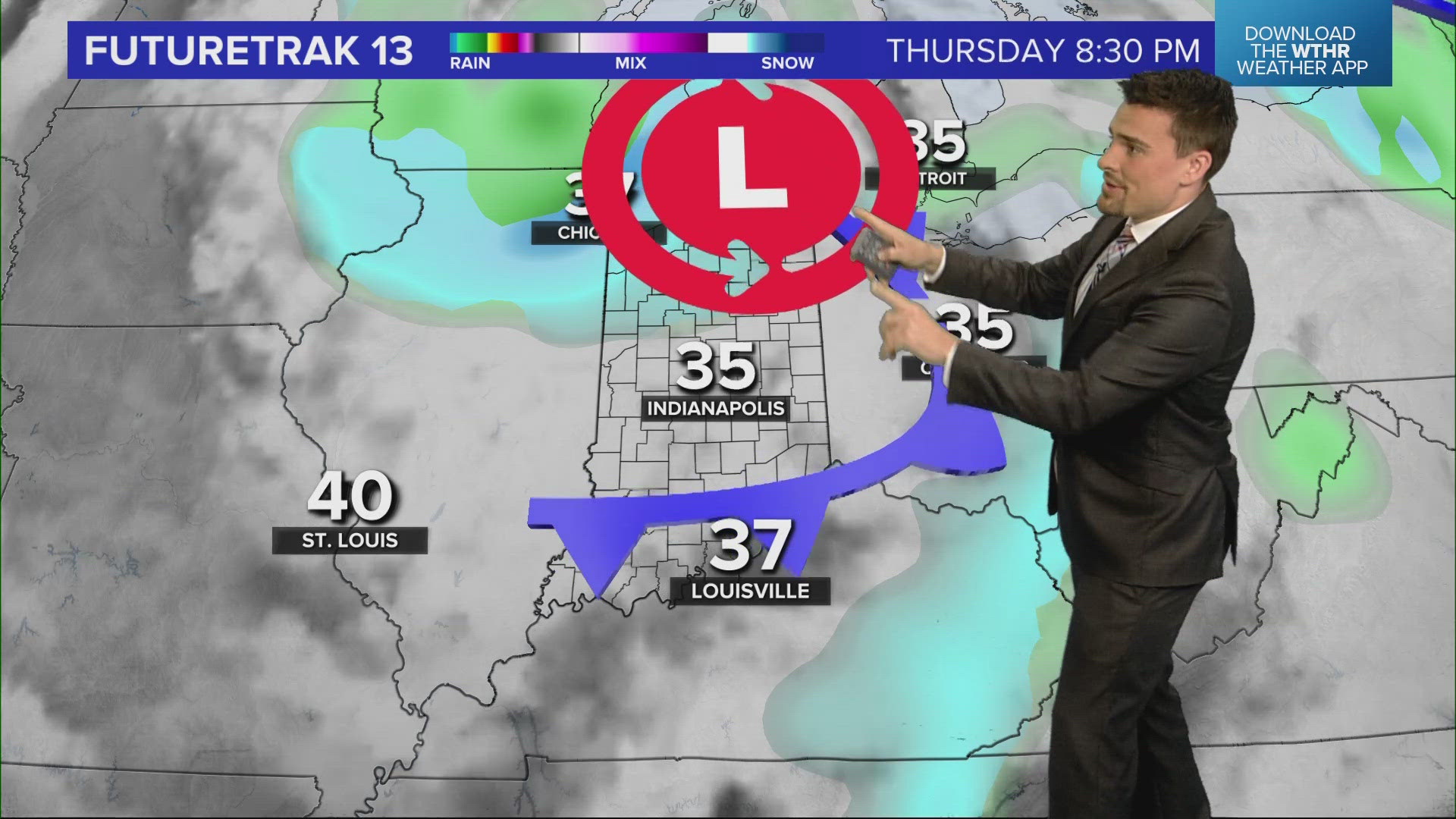

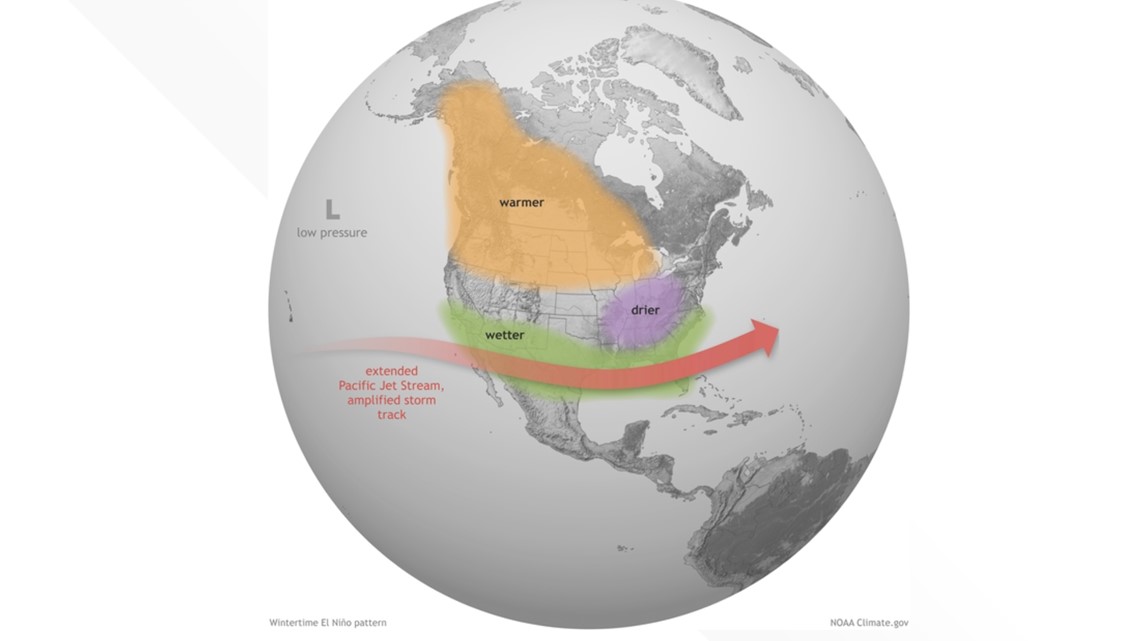

El Niño’s impact on global precipitation and temperature patterns is strongest in the northern hemisphere winter, according to NOAA - both because that’s when El Niño reaches its peak, and because the jet stream, which is influenced by El Niño, is a major player for winter weather.

While no two El Niños are the same, many have temp and precipitation trends in common, according to NOAA.

The combination of cooler weather and more frequent precipitation could also increase the chance of winter precipitation events in the south.

El Niño is just one part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, system - a recurring weather pattern that involves changes in temperature waters throughout the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean that impacts weather around the world.

There are three ENSO phases. ENSO neutral is when surface sea temperatures hover around 75-80 degrees Fahrenheit and is associated with fairly normal winter weather patterns across the U.S.

The Midwest would be dominated by cold temperatures, while the southern U.S. would be warm and wet during this phase. During ENSO neutral, hurricane development would be considered relatively normal, according to the Purdue University College of Agriculture.

Then there is La Niña, the cool phase of the ENSO climate pattern. La Niña conditions can be observed when surface sea temperatures are 0.5 Fahrenheit degrees cooler than normal. The patterns are associated with cold, wet winters across the northern U.S. The south experiences warmer, drier conditions and hurricane development is amplified.

Since 2020, La Niña has been more prominent throughout the United States.

Then there is El Niño, which occurs when surface sea temperatures are 0.5-degree Fahrenheit warmer than normal and contributes to warmer, drier conditions across the northern U.S., and wet weather in the southern US during the winter.

Hurricane development in the Atlantic tends to be lessened, but the development in the Pacific is amplified.

RELATED: NOAA doubles the chances for a nasty Atlantic hurricane season due to hot ocean, tardy El Nino

In the northern part of the U.S., El Niño can lead to a milder winter. That possibly includes the Midwest, because El Niño develops when sea surface temperatures are warmer than average in the equatorial Pacific for an extended time.

But to draw a clear, distinct path from high probability of El Niño in winter 2023 to mean we can - with 100% certainty - face a more dry, milder winter isn’t a connection that’s possible to make.

We asked meteorologist Sean Ash why.

One variable among many

Ultimately, Sean says it’s likely too early to tell what specific impact El Niño could have on our winter weather forecast. We’re too far off - and any current projections could very well could change by winter.

We could still experience two-digit snow events even while experiencing El Niño.

“El Niño is one piece of a massive global jigsaw puzzle that will eventually play a role in what happens here in the winter,” Sean said.

Even if the effects of an El Niño are there, it’s not a guarantee they will mean a more mild winter. Other weather systems could become more prominent and impact our overall forecast to a greater extent than El Niño.

“Sometimes, we actually are colder than normal during an El Niño. But there's also other factors, like what's going on in the North Atlantic? What's going on in the West Pacific? What's going on in the east Pacific,” Sean said. "

That’s because the effects of El Niño are known as teleconnections, or changing conditions in one part of the world that affect another part, Sean says.

Those include teleconnections like the Arctic Oscillation, a back-and-forth shifting of atmospheric pressure between the Arctic and the mid-latitudes of the North Pacific Ocean and North Atlantic. The East Pacific Oscillation, a variation in the atmospheric flow pattern across the eastern Pacific, as well as Alaska. The West Pacific Oscillation, a pressure dipole that exists between the Bering Sea and the Pacific northwest of Hawaii and the Madden Julian Oscillations, an eastward spread of large regions of enhanced and suppressed tropical rainfall all impact weather in North America.

"I always caution on trying to throw a lot of weight into one teleconnection," Sean said.

Recurving typhoons in the West Pacific or storms in the Bering Sea will all impact on jet-steams over North America and, therefore, our winter forecast.

"There's still going to be an extremely high degree of uncertainty on what happens," Sean said.

So, take El Niño projections with a grain of salt, know predictions could change and check out our 10-day forecast in the meantime.