LANSFORD, Pennsylvania — Much of Pennsylvania's natural beauty comes from its breathtaking views, from the top of a gorge, out the window of a car or peering out the window of a historic train.

The story of this state cannot truly be told, though, without going down – way down.

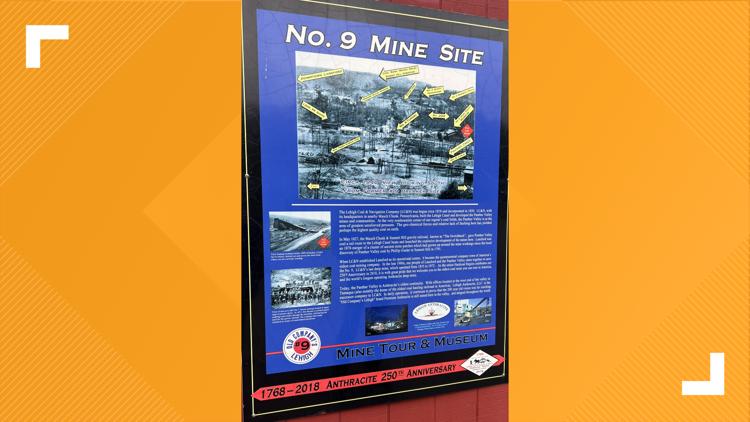

Zach Petroski runs the No. 9 Coal Mine and Museum in Lansford, Pennsylvania, a facility smack dab in the heart of Pennsylvania's anthracite region.

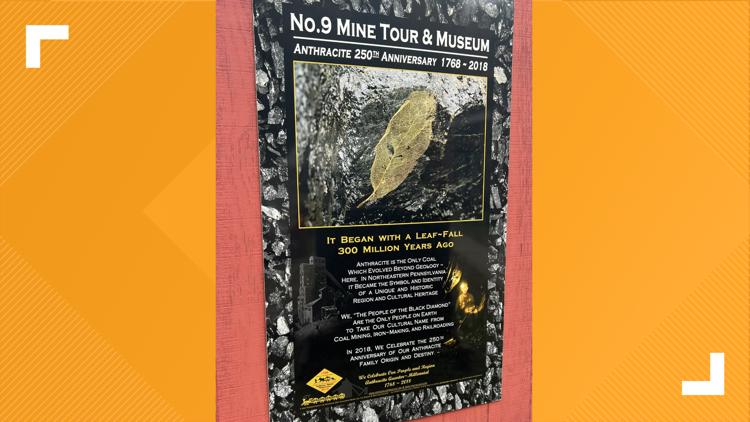

"The two biggest things for many, many years in Pennsylvania for industrial statistics [were] agriculture and mining," Petroski said. "It was always those two big ones. Timber industry was kind of a third one for the most part. Mining was always a close second with agriculture because western Pennsylvania was bituminous industry and northeastern Pennsylvania's anthracite industry."

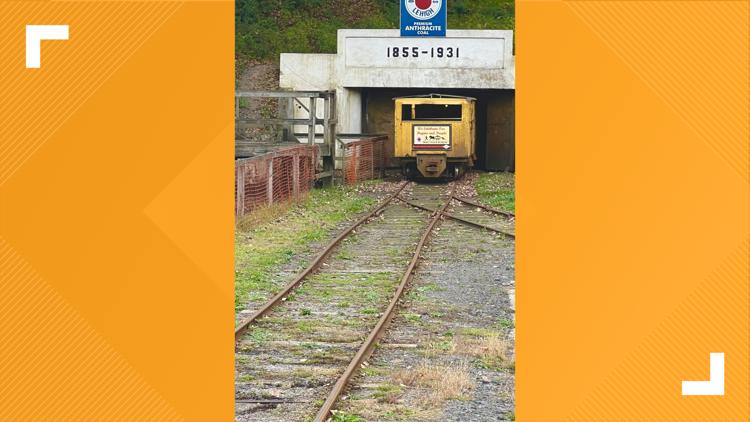

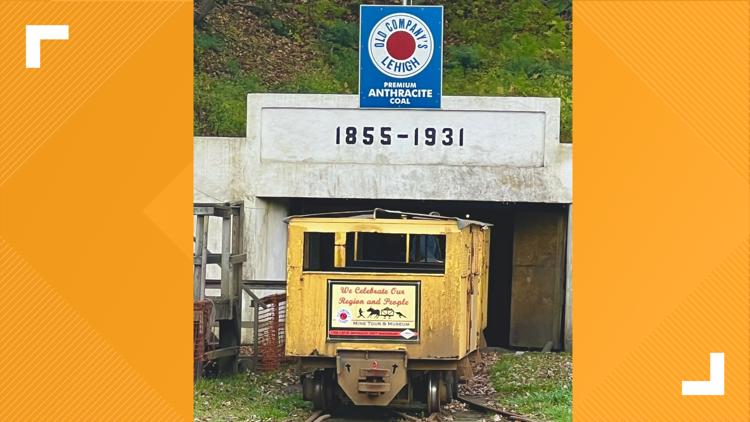

"The two big monikers that our mine shares is we are the oldest coal mine you can tour in the United States, being 170, and this mine was the longest continuously-operated underground anthracite coal mine in the world," he said. "Our mine ran nearly nonstop from 1855 until June 22 of 1972.”

Guests travel via coal car to another world, a world of back-breaking, dangerous work and at times, child labor. Men lost their lives in these mines and were subject to lung disease, heart issues and perilous conditions. Traveling through this underground space, the question comes up: Why would anyone do this for a living?

"We get that question a lot, 'Why would you do this?'" Petroski said. "We're so separated from the Atlantic Migration, the big immigration push in the late 19th century, early 20th century. We're so removed from that we don't think about that. I mean, many of the people that came to work in the mines, this was eastern and northern Europe, the British Isles. They were coming here because it was still, for some parts of eastern Europe, a feudal society. These were poor dirt farmers, essentially. And this was, yes, horrible working conditions, but it was steady pay."

Petroski said the stability was something many didn't have in the late 19th century in Europe.

"You'd have a roof over your head, and you could probably take decent care of your family compared to what you had in Europe at that time," he said.

Chuck's Big Adventure in Pennsylvania: No. 9 Coal Mine and Museum

Most people in this town either worked in the mines or in businesses that supported or provided goods for use in the mines. Remember that when this mine was operating, coal was king. People used it to burn, but that is not the focus now.

"Most coal in general is thought of simply as a fuel," Petroski said. "It was used as a fuel, we still use it as a fuel locally because of the supply is here, but that's not the big focus of the anthracite industry. Anthracite coal, number one use is the production of steel. You need carbon with iron to make a base steel in a blast furnace."

Petroski also said Anthracite coal's purity of carbon "allows you to use it for many processes within the blast furnace."

"Also filter media, carbon filters, everything from industrial grade wastewater treatment filters to small, compact carbon filters can be made with this, really any product that you need carbon for carbon fiber can also be made from this because anything you could theoretically use carbon for you can extract it from coal," he said.

The coal mine dates back to 1855. Guests jump in a mine car and travel 1,600 feet into a mountain, then climb out and take a guided walking tour. They see the original shaft, a miner’s hospital cut into solid rock and get a glimpse of what life was like for men who worked hard and sometimes, gave their life in order feed the insatiable need for coal.

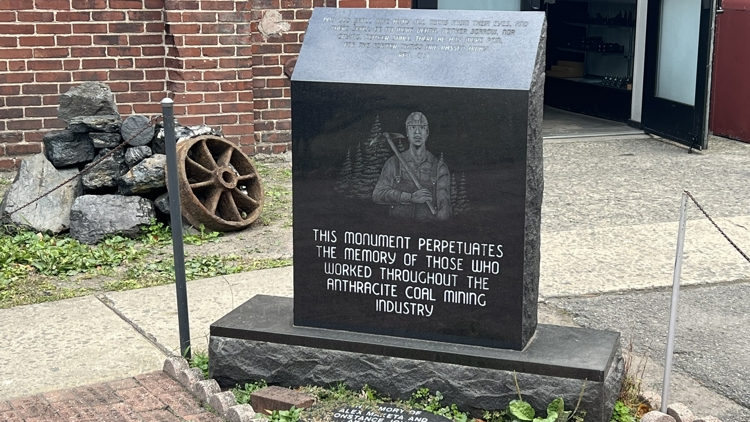

Outside, housed in the No. 9 Mine’s original “wash shanty,” is a museum with coal mining artifacts, a movie and the popular gift shop. For many people, visiting the mine is a connection., a connection with the past and a connection with family who told stories – and now those stories have meaning.

"The interesting thing I've seen over the years is that you will see, not so much the former miners now, of course, many now are quite elderly at this point," Petroski said. "Not so much the children, it's the grandchildren, because they're more separated from it. A lot of the kids around here, it was kind of the same in many mining communities, the parents wanted better for their children. They want to see what grandpa did, but the kids grew up with that notion that, 'Nah, I don't want to go around a mine.' They have a memory that a relative was injured or killed in a mine."

The No. 9 Mine is a trip to the past, a trip to a different day when dangerous work by brave workers moved the wheels of progress. The mine is a must-see in order to fully understand this state, and the men who went deep underground to make a life for themselves, their communities and their country. It’s an underground treasure that is even more valuable in the 21st century to a world that continues to be separated from the age of coal.