INDIANA, USA — In reef caves off the Puerto Rican coast, not far from areas where sunlight may still trickle down through toasty Caribbean waters, lie contingencies of small but mighty creatures, whose bones scientists consider an archive into delicate underwater machinations that took place centuries ago.

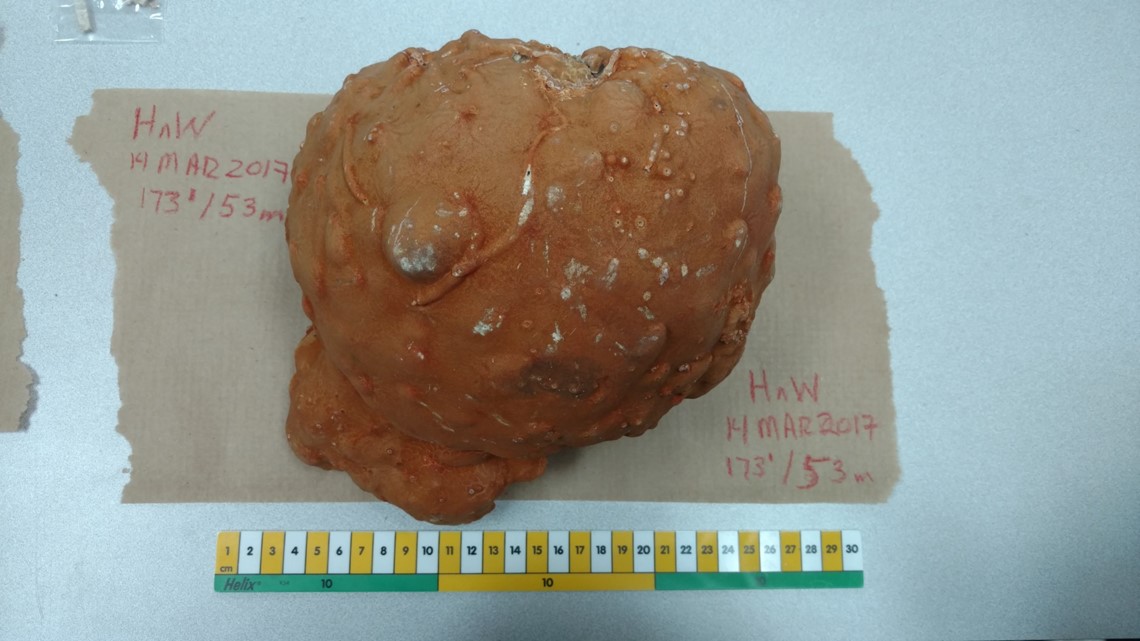

Sclerosponges develop a hardened, limestone skeleton over the course of many centuries that can function as a snapshot into what the environment was like at a given time. A mere 10 centimeters of this species' spongy bone can contain up to 400 years of data and, for scientists studying how our world is warming, can function as an essential thermometer.

Now, a closer look into those fine layers of ancient sea sponge show the world may have already hit a crucial climate tipping point and could very well be hurtling towards another by 2030.

Research published in the science journal Nature Climate Change in early February by a team of scientists who analyzed 300 years of ocean temperatures suggests surface temperatures may have already passed 1.5°C of warming and could exceed 2°C by decade’s end.

“Our data shows that we're nearing the two-degree point very quickly, much faster than has been thought, and that we really need to do something in order to avoid a major change on the planet,” said Dr. Amos Winter, who was an author on the study and is an Earth and Environmental Systems Professor at Indiana State University in Terre Haute.

The team believes their data shows human-caused activity has already raised the global temperature by 1.7°C, not the commonly used value of 1.2°C.

RELATED: Earth shattered global heat record in '23 and it's flirting with warming limit, European agency says

In 2015, world leaders at the UN Climate Change Conference, or COP21, in Paris reached an agreement that they should work to hold global temperature increase to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

“If we go over that, the modeling and other things show that we'll have a difficulty going back from that. The further we go, the harder it will be to recover once we reach it. Two degrees is nearly impossible to recover from. We have to wait centuries,” Winter said.

That the global temperature may have already gone beyond that point scientists around the world was our best chance at mitigating the impacts from a warming world is troubling, said Winter, who collaborated with researchers at The University of Western Australia and University of Puerto Rico Global over the course of 8 years for the study.

“Twenty years ago, the models said we wouldn't be this high and now we're ready beyond what the model said. So, I think, we’re really reaching a danger zone here very quickly,” said Winters.

The new findings on surface temperatures were presented alongside additional research the team thinks shows industrial-era warming began in the mid-1860, which is about 80 years earlier than previously suggested benchmark.

Scientists pulled six live sclerosponges that can only be collected in the eastern Caribbean for the research, to explore what temperatures were like in the ocean mixed layer over the course of 300 years.

They then compared that data to observational records of sea surface temperatures and found stable temperatures from 1700 to 1790 and 1840 to 1860, with a gap defined by cooling connected to volcanic activity, according to the report.

For the reference period between 1961 and 1990, scientists found the ocean mixed layer and land surface temperatures increased by around 0.9C relative to the pre-industrial period, according to the study. That’s more than current estimates from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, which suggest a pre-industrial period of 0.4°C global warming between 1850 and 1900.

“It's the rate of warming, which is unprecedented in history of the Earth, except for, say, an asteroid impact,” Winters said.

But the Caribbean sponge data has prompted some hesitation from other scientists unaffiliated with the study, who have expressed concern that one single point on Earth should not be used as a benchmark to draw conclusions about worldwide warming.

Winter maintains their study’s unique location in the world, and the amount of data collected, makes for a “robust” report. Their team is now working on replying to criticism one-by-one. They are also planning on a page that aims to show why their findings are sound.

“We show exactly why we think our record is better. And if [critics] can, of course, they are welcome to find another record. Criticize us, or whatever, it's fine. That's what science is all about,” Winter said.

In the meantime, Winter is also working to express that reducing your carbon footprint is essential to fighting a warming world, and that everyday changes can make an impact. Every degree, he said, matters.

“The one thing we have to do is not wait until the accident happens, just like crossroads, where you put the lights up after you get the accident, not before, you know, you have to think in advance,” Winter said.

You can read the full report here.