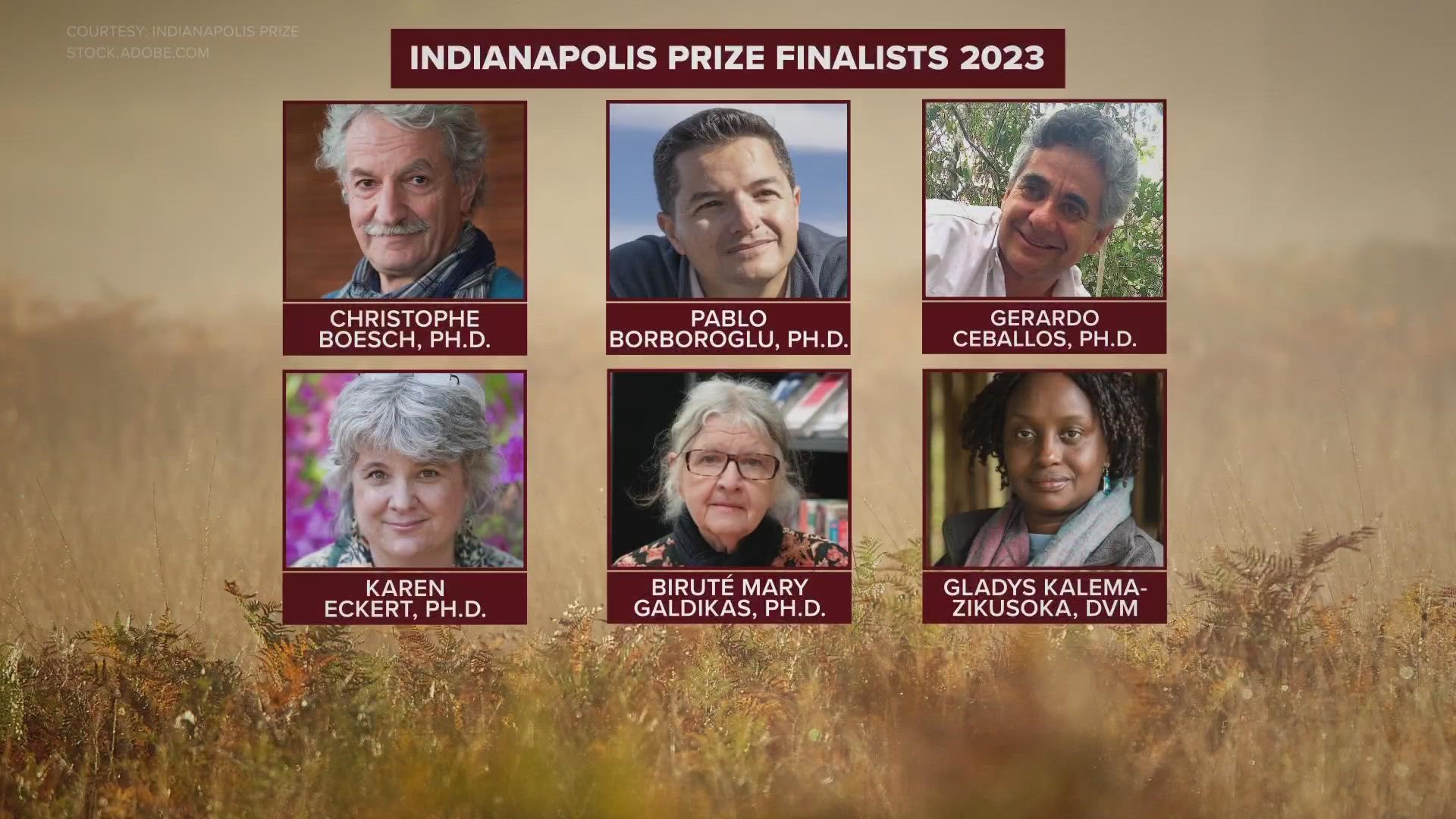

INDIANAPOLIS — Six finalists have been announced in the 2023 Indianapolis Prize, which is an award that recognizes the most successful conservationists who have achieved major victories in saving an animal species or group of species.

"The victories achieved by this diverse group of people are remarkable and deserve our attention," said Dr. Rob Shumaker, president and CEO of the Indianapolis Zoological Society. "They have dedicated decades of their lives to making an authentic difference for many animal species and demonstrate that one person has the power to make a difference."

The winner of the Indianapolis Prize receives $250,000, and five finalists each receive $50,000.

The winner will be announced in May. The finalists and winner will then be honored at the Indianapolis Prize Gala presented by Cummins Inc., on Sept. 30.

2023 Finalists

Biruté Mary Galdikas, Ph.D. (Orangutan Foundation International, USA)

Dr. Biruté Mary Galdikas is a scientist, conservationist and educator working closely with orangutans in their natural habitat in Borneo, Indonesia.

"The great apes are our closest living relatives in the animal kingdom. So, I was very much drawn to them," Galdikas said.

Galdikas is an orangutan researcher who first documented the long orangutan birth interval and recorded more than 400 types of food consumed by orangutans, providing unprecedented detail about orangutan ecology.

Her efforts to stop illegal logging in the forest triggered threats to her life.

"The next time they saw you, they were going to cut you up into little pieces," said Galdikas. "I was in that situation for years, but I never lost my faith. I could never abandon the orangutans to their fate because they were the innocent ones."

Galdikas has contributed to the release of more than 1,000 rehabilitated orangutans into the wild and has rescued and relocated an additional 200 wild orangutans into the wild.

"I was learning they were semi-solitary. I was learning the males fought each other for access to females which had never been thoroughly described," said Galdikas. "I learned what they eat. They were mainly red fruit eaters. I learned the males actually came down to the ground. Sometimes for long periods of time."

Her love for orangutans has fueled her passion for conservation.

"Human greed enables an assault against nature that will not stop," said Galdikas. "The more people realize that we need to put a stop against this assault against nature then maybe governments will come to realize it."

She serves as president and is the co-founder of Orangutan Foundation International, an organization dedicated to protecting wild orangutans in Borneo and their rain forest habitat.

Karen Eckert, Ph.D. (Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network, WIDECAST, USA)

Dr. Karen Eckert specializes in international biodiversity management, conservation and policy with a focus on sea turtles.

Eckert promotes the recovery and sustainable management of sea turtle populations in more than 40 nations and territories.

It began with leatherback turtles in the U.S. Virgin Islands and working to help with their survival.

"I only knew that these were really small populations. They were threatened by everything. I wanted to make sure that they survived through the 21st century, the 20th century at the time," Eckert said.

Eckert began building a team of people in 45 countries to protect the the sea creatures.

"If you're going to save sea turtles, you have to set aside protected areas. You have to deal with coral reefs and seagrass, and perhaps even more difficult, you have to deal with coastal development. You've got to save your beaches," Eckert said.

Eckert has helped protect six species of endangered sea turtles and mobilized community and government support in Caribbean nations to fully protect sea turtles.

"These problems didn't just land on us. They weren't dropped from Mars. Humans created these problems, and I believe the humans can solve them. The more humans involved, the better," Eckert said.

She serves as the executive director of WIDECAST, an organization that facilitates the recovery and sustainable management of sea turtle populations across the globe.

Christophe Boesch, Ph.D. (Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology; Wild Chimpanzee Foundation, Germany)

Dr. Christophe Boesch fights to ensure a future for chimpanzees.

Professor Boesch is a primatologist dedicated to providing alternatives to bushmeat and applying new technology to great ape conservation, decreasing strain on wild chimpanzee populations.

"The chimpanzees are our closest living relative. They look sometimes so incredibly similar to us, and they behave like humans," Boesch said. "In many situations during the day you are with the chimpanzees, and they use tools for this, for honey, for getting an insect, for cracking nuts. All things that, as humans, we would do. They love meat. They are hunting to get that meat. And so, there is a fascination, because when you look at chimpanzees, you look at the behavior of the chimpanzees, you somewhere see something about us there."

He uncovered the effects of rapid deforestation across sub-Saharan Africa and promoted new areas for protecting the remaining chimpanzee populations in Guinea.

Boesch says chimpanzee behavior differs depending on where they live.

"We have 36 behaviors that were different in different chimpanzee populations to the point where you tell me how a chimpanzee behave, I can tell you where it comes from," Boesch said.

Boesch says chimpanzee populations have declined 80% in the last 20 years in West Africa making them "critically endangered."

That's why conservation projects are so important.

"I mean the real threat to chimpanzees nowadays is habitat destruction, and the main threat for that is agriculture. Agriculture cuts all the forest," said Boesch. "I think if you want to guarantee some hope of survival for the chimpanzees, we need to create new national parks in West Africa, where the chimpanzees are present," Boesch said.

He was a finalist for the 2021 Indianapolis Prize.

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, DVM (Conservation Through Public Health, Uganda)

Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka is a wildlife veterinarian recognized globally for her work protecting endangered mountain gorillas in East Africa.

"So, a good day for me is just going to the forest and spending time with the gorillas when they're relaxed. I get a lot of inspiration by being with them. It's very therapeutic being with the gorillas," said Kalema-Zikusoka.

She promotes conservation by cultivating an understanding of how humans and wildlife can coexist in protected areas in Africa.

Kalema-Zikusoka said there are very few women working in a wildlife career.

"Even when you'd go to Europe or America, there were very few women in the wildlife sector in general. Even South Africa actually did not have female wildlife vets. It had only male wildlife vets who I would work with quite a lot," said Kalema-Zikusoka.

Dr. Kalema-Zikusoka is the mother of two boys and learned something very interesting about gorilla families.

"Gorillas are really good at spacing, birth spacing. They have a baby once every four years without modern family planning, once every four to five years. I mean, basically, they breastfeed for three years and then they conceive," said Kalema-Zikusoka. "And it's very logical because, by the time the new baby is born, the older one can look after the younger one. And so, we spaced our boys like the gorillas, which worked out really well."

She is the founder of Conservation Through Public Health, an organization promoting biodiversity conservation by enabling people and wildlife to coexist by improving health and livelihoods in and around Africa's protected areas.

Pablo Borboroglu, Ph.D. (Global Penguin Society, Argentina)

Dr. Pablo Borboroglu is a protector of ocean and coastal habitats for penguins in several countries including Argentina.

Borboroglu works to improve penguin colony management through the creation of large, protected areas, including 32 million acres of ocean and coastal habitat.

He is the co-founder and leader of the Global Penguin Society, an international conservation coalition for the world's penguin species.

His first memory of penguins came from his grandmother when he was a toddler.

"She used to tell me the stories when she visited penguins a hundred years ago in Patagonia, which is a place where I live and I work. And then she used to tell me this amazing stories and for me, was something really remote, because in the place where I was born, even though there was an ocean, there were no penguins," said Borboroglu.

His concern for penguins started in the 1980's when he heard tens of thousands of penguins were dying every year from oil spills.

"I used to pick up oiled penguins on the beach to rehabilitate them and then release them back into the wild," said Borboroglu.

When media attention resulted in oil tankers sailing further offshore the penguin population improved.

"Imagine in the '80s, 40,000 penguins died due to oil spills. Now I would say that less than 20 individuals die," said Borboroglu.

He's using the plight of the penguins to do more than protect one species.

"So through penguins, we protect the oceans and we protect many other species," said Borboroglu. "We also protect human beings because the oceans are critical for the survival of all the planet."

Borboroglu is also the founder and co-chair of the International Union for Conservation of Nature Species Survival Commission Penguin Specialist Group.

Gerardo Ceballos, Ph.D. (Institute of Ecology, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico)

Dr. Gerardo Ceballos is at the forefront of groundbreaking research and animal conservation in Mexico. He acted as a key proponent in the passage of the country's Act for Endangered Species, which now protects more than 40,000 animals.

"Life on Earth depends on the wild plants and animals," said Ceballos.

Ceballos is a champion for jaguars in Mexico, conducting the first country-level jaguar census.

"If you protect jaguars, you protect the forest," said Ceballos.

Ceballos said the jaguar population has increased from 4,000 to 4,800 in Mexico. He says if people take care of the habitat the jaguars can survive and flourish.

"By protecting the Jaguar, we're protecting large areas with many other species," said Ceballos.

Ceballos has been working the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve for 25 years.

"We propose to the Mexican government to increase of the area because of its jaguars," said Ceballos. "Increasing the area will not only increase the size of the populations of jaguar twice the size, but also will protect many other endangered species."

Ceballos says if you protect jaguars you protect thousands of species of plants, animals and micro-organisms.

"By saving these forests, by saving these animals, okay, you're also basically saving humanity," said Ceballos.

Ceballos developed successful conservation strategies for endangered mammals in North America, including the black-footed ferret.

"The ultimate goal for all of us is to protect all ecosystems still left in the planet. We don't have time, we're running out of time. We still have time to save most of this balance and animals of this planet, but the window of opportunities closing," said Ceballos.

He was a finalist for the 2010, 2014 and 2021 Indianapolis Prize.