WALLER, Texas — A.J. Foyt was 15 when a boat that he and two friends were riding in capsized in a storm. The young Foyt clung tightly to a buoy until a fishing vessel found him, too late for one of the other boys that had already drowned.

Not long afterward, Foyt and some buddies were climbing towers and one of them grasped a power line and was electrocuted. Foyt will have you know that he never considered touching those lines.

So began a life spent cheating death, one that one of the greatest auto racing drivers in history has been forced to reflect upon in recent weeks during what usually is a time of joy. The month of May means the Indianapolis 500, the biggest race in the world, and it's a crown jewel event that Foyt won a record-sharing four times.

Lucy, his beloved wife for nearly 68 years, died last month. For Foyt, now 88, the prospect of mortality has finally become inescapable. And few have had so many escapes.

Foyt was retired when he suffered two near-fatal attacks by killer bees, one sending him into shock. He once flipped a bulldozer into a pond on one of his Texas properties, emerging to shout: “I ain’t no Houdini! I needed some air!” He has had several staph infections, one leading to a concrete spacer in his leg that eventually led to an artificial knee.

When Foyt had triple bypass surgery a decade ago, he was left comatose; Lucy was told his organs were beginning to fail. Yet his high school sweetheart had seen him defy death so many times that she refused to turn off his respirator. Naturally, he recovered.

And then there are the wrecks, so many of those. Like his 1965 flip in a stock car at Riverside, when doctors on site pronounced him dead. Parnelli Jones stepped in, scooped dirt from Foyt’s mouth and that was all it took to revive him.

Or the crash in 1972, when Foyt had to leap from a burning dirt champ car. It ran over his ankle and broke it as Foyt, engulfed in flames, ran toward a pond. His father grabbed a fire extinguisher to save his son.

That brings his story to March 7 of this year, when Foyt went to a Houston hospital to have a pacemaker installed. He was deeply opposed to the procedure, mostly because he believes a pacemaker killed his mother in 1981. He asked the doctors what would happen if he didn’t get it.

“I think they were scared my heart was slowing down too much,” said Foyt, who has never slowed down a day in his life. “(The doctor) said the bad thing was you can pass out or have a stroke. Well, I didn’t want to be driving from Houston out here to the shop and pass out and kill somebody. So that’s the reason I did it, because I still like to drive my own car.”

He showed up on time for the procedure, Lucy by his side, and they waited — and waited and waited.

“They told us to be there at 5:30, so OK. It got to be about 10:30-11 and they said, ‘It might be another hour or two,’” Foyt recalled. “I said, ’You can forget it and stick it up your ass.’ I started to put my underwear and pants on and was walking out. They said, ‘No, no, no, we’re gonna get you right in.’ If it was an emergency, it would be one thing. But they want me to sit there another couple hours? They can go to hell.”

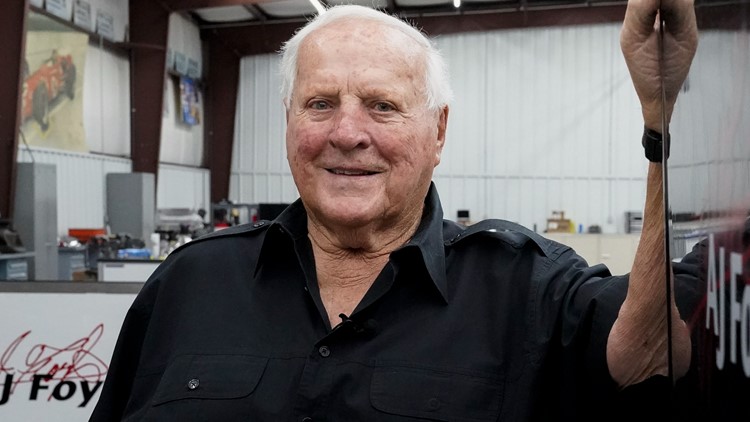

The Associated Press recently spent a day with Foyt at his race shop in Waller, reminiscing about a colorful career that made him famous far beyond the track. He was same ol’ A.J. that day, cracking jokes, talking about his ranches, career milestones and how, unlike longtime rival Mario Andretti, he had no issues with isolation or depression during the pandemic.

“That’s Mario Andretti. That ain’t A.J. Foyt,” he said with a snarl.

The tough-as-boot-leather Texan was irreverent about death that day, too. Foyt drove during one of the deadliest eras in motorsports, and far too many of his racing contemporaries pulled off pit lane never to pull back in. The number of those who survived is dwindling with time, of course; two good friends not only died on the same day earlier this year but had funerals on the same day, too.

“What do you do when your friends die? You get new friends,” Foyt said with a shrug.

It's not so easy to replace Lucy, who died unexpectedly just seven days after AP visited Foyt.

“Super Tex” had just spent the first weekend in April at Texas Motor Speedway, attending his first IndyCar race of the season to watch his two drivers compete. He and Lucy have what he called “sugar diabetes,” and when Foyt called her over the weekend, she mentioned that she wasn't feeling well.

By the time Foyt arrived home Sunday night, she was far worse. Foyt on Tuesday finally got her into an ambulance to the hospital, but Lucy suffered a massive heart attack. She died the following morning.

“The nurses, they knew who I was," Foyt said, “and they came out and told me the treatments weren't doing nothing, and they said, ‘Mr. Foyt, it’s bad.'”

The nurses promised to get him from the waiting room to her bedside at the end; in a blink-or-you'll miss it moment, Foyt's eyes briefly welled with tears and his voice choked as he discussed their final goodbye.

“Me and my oldest son sat there next to the bed with her,” Foyt said, taking a long pause, “and it was hard.”

Foyt said he once told Lucy she couldn't die first, yet that's what happened. And he was relieved by it.

“I'm kinda glad she died, and I hate to say it like that, but once your heart stops, your lungs, your kidneys, never recover," Foyt said. “She couldn't live like that. I wouldn't want her to.”

The couple shared four children, eight grandchildren and 21 great-grandchildren. They owned several properties across Texas, many of them working cattle ranches that Foyt tends to to this day. He now has to handle her affairs, too, and when he talks about the challenges ahead it becomes clear that he remains every bit as ornery as he was his entire career. Heck, in 1997, at the age of 62, he wrestled Arie Luyendyk to the ground at Texas Motor Speedway when the Dutch driver showed up at a Foyt victory celebration claiming he had won.

Take Foyt's trip to the funeral home, where a relative made an outfit suggestion for Lucy's burial. Too many people suddenly had their own ideas about the memorial. Foyt sat silent — for a while.

“I said, ‘Let me tell you, you ain’t making one goddamn decision. I'm gonna bury her the way I want her buried, not what y'all think,'" Foyt said. "I probably shouldn't have blowed up, but I got mad and said, ‘Y’all shut your (expletive) mouths — excuse my language — I'm making the decisions so you all get the (expletive) out of here.

“The lady at the funeral home, she said, ‘You don’t put up with no nothing!' And I said, “No ma'am, not when it's my decision.'”

Foyt decided his wife would be buried in yellow — “Yellow is what she loved, and what she looked good in" — and he picked out a casket and draped it in yellow flowers, which he had given her each year. He refused to have the casket lowered into the ground while he was present.

Foyt didn't want to go to Indianapolis this month, worrying about what could happen at home without Lucy to oversee things. But he figured Indianapolis Motor Speedway, that historic gray lady on Georgetown Road where he had spent many of his best days, was the right place to help process his grief.

“I said, ‘Well, I need to get away,'" he said, "so that’s the reason I'm here.”

From the garages of Gasoline Alley to the yard of bricks on the front stretch, Foyt is surrounded by old friends and foes, racers everywhere — his kind of people — along with adoring fans who believe Foyt is the best to walk the hallowed grounds.

“I still consider him the greatest driver to ever pull on a helmet,” three-time Indy 500 winner Johnny Rutherford said.

Foyt won his first Indy 500 in 1961, then again in 1964 and 1967, while his 1977 victory made him the first four-time winner, a club that has grown to include Al Unser Sr., Rick Mears and Helio Castroneves. Foyt qualified for “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing” for 35 consecutive years, and he is the only driver to win in both front- and rear-engined cars.

His legacy extends well beyond the Indy 500. In 1967, Foyt became the only driver to win the 24 Hours of Le Mans and Indy 500 in the same year, and he's the only driver to have won Indy, the Daytona 500, Le Mans and the 12 Hours of Sebring. He has 12 major racing championships – his seven IndyCar titles are a record – and his 67 IndyCar victories are most in series history.

Foyt even holds the closed-course speed record, which he set in 1987 on a test track near Fort Stockton, Texas, where he drove an Oldsmobile Aerotech at an average speed of 257.123 mph. He was 52 at the time.

The track is where he belongs, and it is why he reluctantly left Texas to spend another May in Indianapolis.

His eponymous race team has gone through some lean years, split between shops in Waller and Indianapolis. The Waller facility has only eight full-time employees, but it is where Foyt said his flagship No. 14 will remain “until the day I die.”

Santino Ferrucci is driving it this year, and the chassis for Sunday’s race was on display in Waller the day the AP visited. His crew felt confident it had built a bullet, and the optimism wasn’t misguided: Ferrucci will start fourth — the same position Foyt started when he won his final two Indy 500s — while rookie teammate Benjamin Pedersen will roll off 11th.

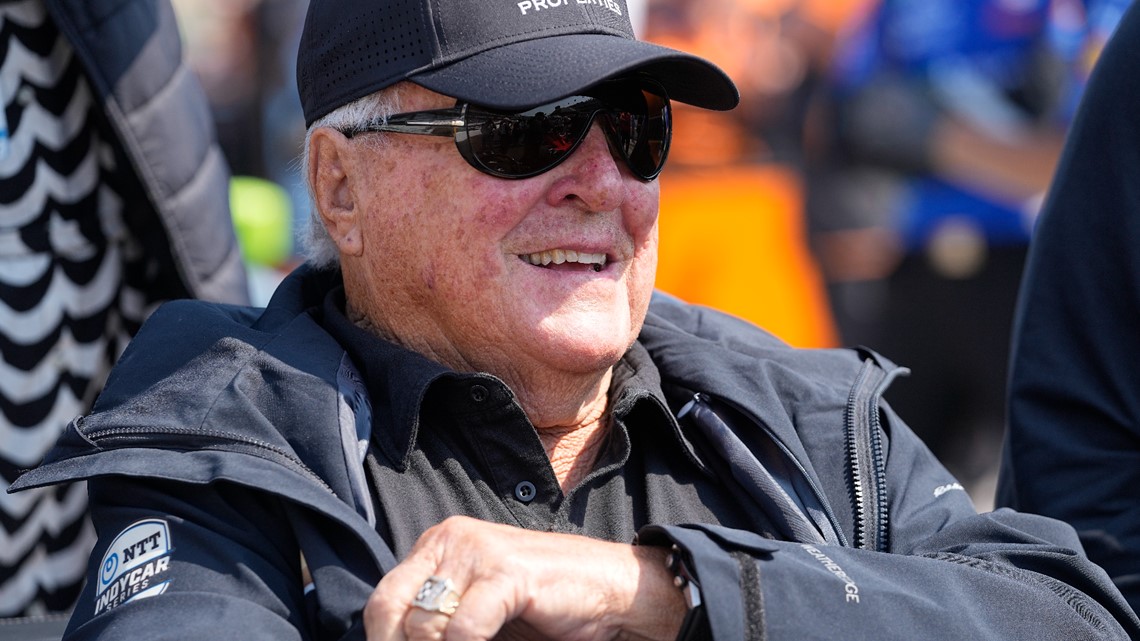

Foyt, who has lost about 50 pounds this year but whose mobility is slowed by foot problems, watched some of the qualifying laps last weekend from a golf cart on pit road.

“It’s good to see him," Ferrucci said, "and I know for a fact in the garage he was really, really happy to see the car and see the progress, to see something he hasn’t seen out of this team in a long time as far as build quality and all the work and development that has gone into this car. He’s super excited. It’s a huge confidence boost for the whole organization.”

The excitement of qualifying weekend was tempered a bit when Foyt turned toward Anne Fornoro, his publicist since 1985. Her husband, an accomplished racer and National Midget Auto Racing Hall of Famer Drew Fornoro, died May 1, and the Foyt and Fornoro families are tightly intertwined. Fornoro and her daughter were overcome by emotion, and Foyt looked at Fornoro and made a sobering realization: “I have no one to call now.”

It would have been Lucy awaiting the day's results back home.

The thought brought Foyt's son, Larry, to tears. He is the one that runs the day-to-day operations for the race team. Born to Foyt's only daughter, Larry was adopted and raised by A.J. and Lucy and he recently named his newborn daughter Lucy.

Running an underfunded race team is hard enough. Doing it with Foyt over your shoulder is pressure that Larry Foyt has learned to accept.

“It gets better with time, for sure. I mean, just as A.J. has gotten older, right?” Larry Foyt said. “But anything big, I always run by him. We collaborate on pretty much everything. But lately, some health things came about.”

The elder Foyt was not present for the team's last win — a victory by Takuma Sato at Long Beach a decade ago — but that win earned Larry Foyt some autonomy within the race team.

“I think when that happened, he realized, ‘Hey, OK, maybe things are OK when I’m not on top of it all the time,'” Larry Foyt said. “And that's what we're working on, just trying to get the team back to where he can enjoy it. Give him something to root for and be proud of the race team.”

Team morale is soaring headed into Sunday's race, and fans each day at the track have shown their adoration for Foyt and his drivers. The qualifying crowd last Sunday roared for Ferrucci each time he took to the track, including his run for the pole. By that point, a superstitious Foyt was watching from one of the garages, the door pulled shut.

Ferrucci wound up fourth, and Foyt couldn't help but feel a little disappointed. But he was quick to mention that, despite his own four poles, he never won the Indy 500 starting from the front row.

In the afternoon sun, a crowd was building outside his garage, waiting for Super Tex to emerge so they could cheer his team's encouraging start to the Indy 500. The lowest-ranked, full-time team in IndyCar had out-qualified mighty Team Penske, and most of the cars from heavyweights Chip Ganassi Racing and Arrow McLaren Racing.

The fans were bursting with pride for Foyt, who simply wanted to move on with his day.

“I don't care how anyone else feels,” he said. “I only give a (expletive) how A.J. Foyt feels.”