NEW YORK — The world solemnly marked the 20th anniversary of 9/11 on Saturday, grieving lost lives and shattered American unity in commemorations that unfolded just weeks after the bloody end of the Afghanistan war that was launched in response to the terror attacks.

Victims' relatives and four U.S. presidents paid respects at the sites where hijacked planes killed nearly 3,000 people in the deadliest act of terrorism on American soil.

Others gathered for observances from Portland, Maine, to Guam, or for volunteer projects on what has become a day of service in the U.S. Foreign leaders expressed sympathy over an attack that happened in the U.S. but claimed victims from more than 90 countries.

“It felt like an evil specter had descended on our world, but it was also a time when many people acted above and beyond the ordinary,” said Mike Low, whose daughter, Sara Low, was a flight attendant on the first plane that crashed.

“As we carry these 20 years forward, I find sustenance in a continuing appreciation for all of those who rose to be more than ordinary people,” the father told a ground zero crowd that included President Joe Biden and former presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton.

In a video released Friday night, Biden said Sept. 11 illustrated that “unity is our greatest strength.”

Unity is “the thing that’s going to affect our well-being more than anything else,” he added while visiting a volunteer firehouse Saturday after laying a wreath at the 9/11 crash site near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. He later took a moment of silence at the third site, the Pentagon.

The anniversary was observed under the pall of a pandemic and in the shadow of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, which is now ruled by the same Taliban militant group that gave safe haven to the 9/11 plotters.

“It’s hard because you hoped that this would just be a different time and a different world. But sometimes history starts to repeat itself and not in the best of ways,” Thea Trinidad, who lost her father in the attacks, said before reading victims' names at the ceremony.

Bruce Springsteen and Broadway actors Kelli O'Hara and Chris Jackson sang at the commemoration, but by tradition, no politicians spoke there.

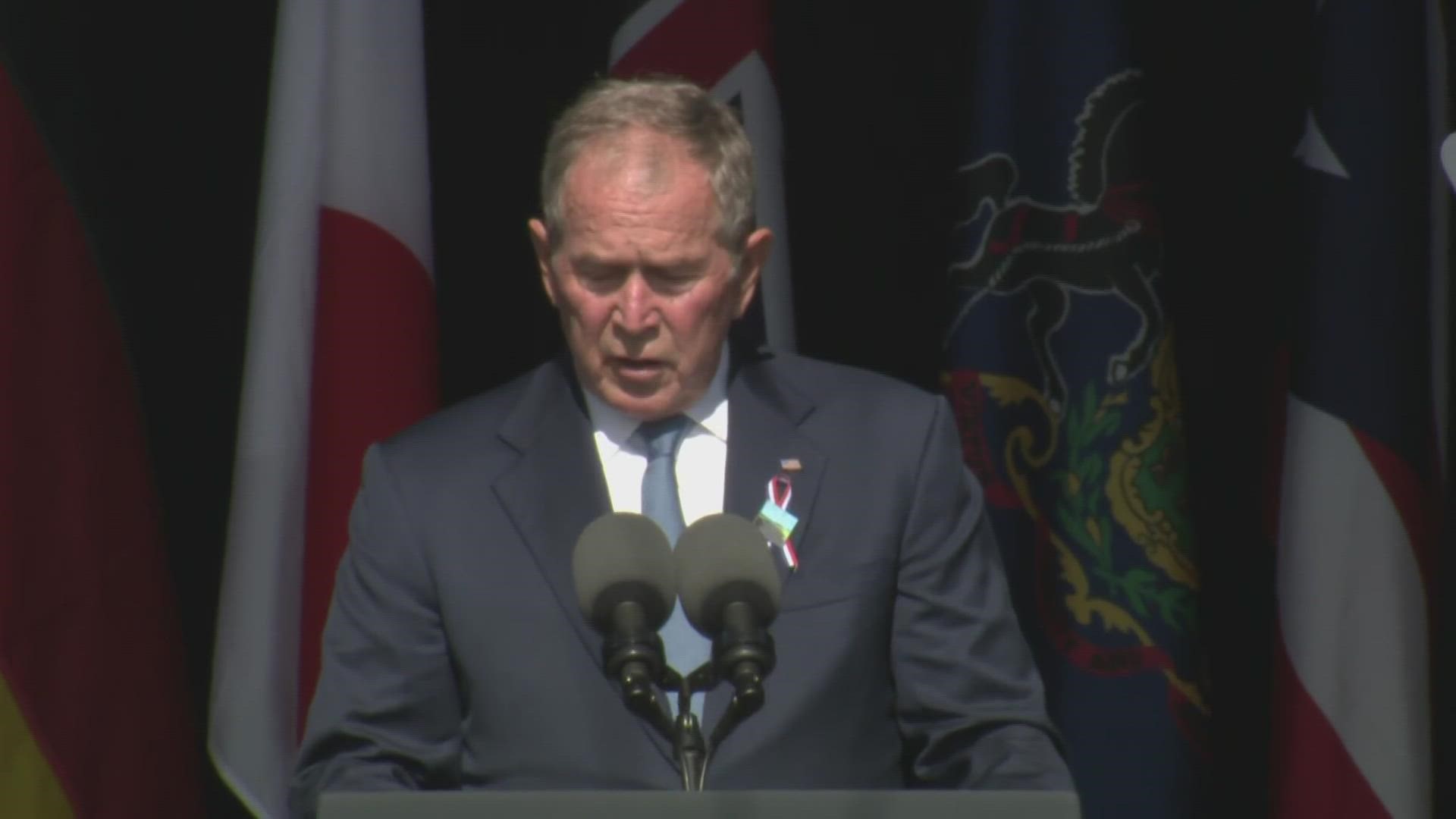

At the Pennsylvania site — where passengers and crew fought to regain control of a plane believed to have been targeted at the U.S. Capitol or the White House — former President George W. Bush said Sept. 11 showed that Americans can come together despite their differences.

“So much of our politics has become a naked appeal to anger, fear and resentment,” said the president who was in office on 9/11. “On America’s day of trial and grief, I saw millions of people instinctively grab their neighbor’s hand and rally to the cause of one another. That is the America I know.”

"It is what we have been and what we can be again.”

Calvin Wilson said a polarized country has “missed the message” of the heroism of the flight's passengers and crew, which included his brother-in-law, LeRoy Homer.

“We don’t focus on the damage. We don’t focus on the hate. We don’t focus on retaliation. We don’t focus on revenge," Wilson said before the ceremony. "We focus on the good that all of our loved ones have done.”

Former President Donald Trump visited a New York police station and a firehouse, praising responders' bravery while criticizing Biden over the pullout from Afghanistan.

“It was gross incompetence,” said Trump, who was scheduled to provide commentary at a boxing match in Florida in the evening.

The attacks ushered in a new era of fear, war, patriotism and, eventually, polarization. They also redefined security, changing airport checkpoints, police practices and the government's surveillance powers.

A “war on terror” led to invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, where the longest U.S. war ended last month with a hasty, massive airlift punctuated by a suicide bombing that killed 169 Afghans and 13 American service members and was attributed to a branch of the Islamic State extremist group. The body of slain Marine Sgt. Johanny Rosario Pichardo was brought Saturday to her hometown of Lawrence, Massachusetts, where people lined the streets as the flag-draped draped casket passed by.

The U.S. is now concerned that al-Qaida, the terror network behind 9/11, may regroup in Afghanistan, where the Taliban flag once again flew over the presidential palace on Saturday.

Two decades after helping to triage and treat injured colleagues at the Pentagon on Sept. 11, retired Army Col. Malcolm Bruce Westcott is saddened and frustrated by the continued threat of terrorism.

“I always felt that my generation, my military cohort, would take care of it — we wouldn’t pass it on to anybody else,” said Westcott, of Greensboro, Georgia. “And we passed it on.”

At ground zero, multiple victims’ relatives thanked the troops who fought in Afghanistan, while Melissa Pullis said she was just happy they were finally home.

“We can’t lose any more military. We don’t even know why we’re fighting, and 20 years went down the drain,” said Pullis, who lost her husband, Edward, and whose son Edward Jr. is serving on the USS Ronald Reagan.

The families spoke of lives cut short, milestones missed and a loss that still feels immediate. Several pleaded for a return of the solidarity that surged for a time after Sept. 11 but soon gave way.

“In our grief and our strength, we were not divided based on our voting preference, the color of our skin or our moral or religious beliefs,” said Sally Maler, the sister-in-law of victim Alfred Russell Maler.

Yet in the years that followed, Muslim Americans endured suspicion, surveillance and hate crimes. Schisms and bitterness grew over the balance between tolerance and vigilance, the meaning of patriotism, the proper way to honor the dead and the scope of a promise to “never forget.”

Trinidad was 10 when she overheard her dad, Michael, saying goodbye to her mother by phone from the burning trade center. She remembers the pain but also the fellowship of the days that followed, when all of New York “felt like it was family.”

“Now, when I feel like the world is so divided, I just wish that we can go back to that,” said Trinidad, of Orlando, Florida. “I feel like it would have been such a different world if we had just been able to hang on to that feeling.”

___

Associated Press writers Michael Rubinkam in Shanksville, Pennsylvania; David Klepper in Providence, Rhode Island; Jill Colvin in New York; and Alexandra Jaffe in Shanksville and Washington contributed to this report.