INDIANAPOLIS — The station has asked that I write a blog about my 30 years at WTHR. Pretty daunting assignment if you ask me, but I am still getting paid so thought I had better give it a go.

I will start with my very first day at WTHR.

We were standing in front of the Indiana Statehouse near the bus stop that is still there. One man was sitting there alone. Not sure whether he was waiting for a bus or just waiting. He looked up and saw me and the TV cameraman and without missing a beat dropped his head back into his hands and asked "Do you work at Channel 13?"

"Yes," I replied, kind of puffing my chest out on my first day.

"You ain't Bob Gregory. You ain't Tom Cochrun and you ain't Don Hein. Hell you ain't nobody," he declared with his head still resting in his hands.

I was caught off guard, but it didn't take me all that long to realize he was right.

I have to admit, I came to WTHR hoping to be an anchor. I wanted all the acclaim and financial rewards that came with that but those of course were all the wrong reasons.

When our political reporter departed, I was the only one who wanted the beat. No one wanted to get tied up at the Statehouse, but I did. I only missed one national political convention since 1988. Being a history major, it gave me a chance to touch history.

I have so many memories.

I remember standing in line to get a floor pass when a gaggle of people ran by carrying campaign signs. It sounded like a small herd of cattle. An old wily print veteran behind me noticed my surprise and deadpanned, "What's a matter? Haven't you ever seen a spontaneous demonstration preparing to break out before?" I had not. It was my first.

I was there in 1988 when Ronald Reagan gave his farewell address to the GOP in New Orleans. When Dan Quayle was nominated to be Vice President. I was at the Riverfront when VP George Bush announced his choice. In fact, the Senator walked up next to me as he was preparing to go on stage.

"You are his choice," I said to him.

"I will not upstage the Vice President," he countered. The rest is history. No one believed it would be Dan Quayle. My instincts were to go no matter what. I was right.

After the last night, the traffic was so bad many members of the press congregated at a local pub to wait it out. I am so glad I joined them. They were all talking about Reagan's speech. Sam Donaldson was holding court. Doing his best Reagan imitation of the speech, much to the joy of those nursing their beers. He said Reagan's speech was not up to his normal standards. I thought the Gipper was tremendous, but I didn't think so much of Donaldson's imitation.

By 1995, my career at WTHR seemed to be floundering. It was now clear I would not be an anchor.

Then everything changed April 19, 1995 with the bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. I was on a plane and broadcasting from there by the evening news. This proved to be a pivotal assignment for me.

There was no time to wallow in whatever problems I might have had. Mine were minuscule compared to this. Looking back, this is where the man on the bench in front of the statehouse got it right. I was nobody. This was all about the victims, the country and the future. It may sound odd, but by disappearing into a story I actually found myself.

It would all come back again September 11, 2001. We drove all night. Getting to New York the morning of the 12th. In fact, when we arrived at a New Jersey hotel to check in early that morning a producer was trying to secure a room for Brian Williams who was standing behind him.

I vividly remember going into the city the next day on The Path. The ticket taker walked into our car. I stood up to tell him I did not have a ticket and he said, "Sit back down and don't worry about it. You are the only one on this train."

I wondered what we were getting into, but I had no reservations about where I needed to be. The story was in front of me. I will never forget what I saw when we emerged from the underground station. People were huddled together — praying. Dust was everywhere in the air. I thought I had walked onto a Hollywood movie set, except this was real.

For the next week, our crew worked out of our car. Finding Hoosiers wherever we could. I was, and still am, so proud of Task Force One. I have many pictures of our time there. Most really cannot be shared, but I pull them out every year on the anniversary and it all comes back to me.

It was not just the big stories however. I saw a postcard once that read: "I'm not interested in whether you stood with the great. I'm interested in whether you sat with the broken." I have many times, and their stories are just as memorable to me.

I remember the story of a little girl who wanted to go to the neighborhood store. She wanted to take her younger sister. I can't remember her exact age, but I think she was 10 or 12. She pleaded with her mom saying she would be careful. Her mom finally gave in but decided to call the store to make sure they got there okay. The clerk answered saying yes she could see them. They were getting ready to cross a busy road. Their first step into that road would be their last. They never made it. I remember that story like it was yesterday and always will. I still cry just as hard today as I did then.

I remember when I was on assignment in Macedonia during the Bosnian conflict. We were following a band of Hoosiers taking supplies to the war zone. One day we stopped at this farmers house near the border. He proceeded to tell me he had moved out of his house and into the shack where the farm animals were normally housed. "Why did you do that?" I asked.

"I gave my house to the women and children coming out of the mountains," he said. All their men had been slaughtered. "If you want to look at food, go to a rich man's house," he explained to me. "But if you want to eat, go to a poor man's house." I never forgot his words or his deeds.

As we were preparing to leave, a woman gathered all the children around us. Probably numbering 15 or so, she asked how many of them would like to come to America? They all raised their hands. All their faces were looking directly at me, asking me to take them back to America. I had to get away, so I started walking down this long road. I had no idea where I was going. My translator ran after me. He put his hands on both of my shoulders and told me, "There were poor here before the war, and there will be poor after the war."

Trust me, I can still see those faces.

If you think for a minute that we are cold and heartless, you couldn't be more wrong. I am sure I am not the only one who has stories they don't talk about but can never forget.

Luckily for me, another option came along at just the right time. I was asked if I would be interested in telling stories about Hoosiers. Only in Indiana was born. It gave me the chance to disappear once again into the stories of ordinary Hoosiers doing spectacular things. Whether it was building a roller coaster in the backyard, or finding a videotape of your son who was lost to drug overdose and allowing us to watch it with them for the very first time. I had the opportunity to travel to West Virginia to tell the story of an Indiana family who made the move to allow their son to learn how to play the fiddle at the foot of the masters. Let me tell you. It was an honor for me each and every time I was allowed to tell these stories. Some were gut wrenching and some were downright hilarious, but I wouldn't have missed any of them.

RELATED: Only In Indiana: The Ring

I know someone may wonder why I have not talked about the last political campaign. In many ways this is when I knew I was getting close to the end of my journalism career. I had reached the mountaintop. All my life I had wanted to cover a Presidential campaign — 2016 made that all possible. I rode in the motorcades. I interviewed Gov. Mike Pence in the air aboard Trump 2 after he had secured the nomination. And I sat down for what would be the first of two one-on-one interviews with nominee and then President Donald Trump.

It was a dream come true. Not because of who was involved, but because it was a dream of mine that was coming true.

When I was growing up in tiny Lexington, Nebraska — Senator Robert Kennedy's campaign train came through town. That was a big deal. Even as a 10-year-old boy, I knew I wanted to be there. I can still tell you what he talked about that day and see Ethel standing behind him. When the speech ended, I did something only a child would do. I jumped on the back lip of the train and grabbed on the railing with my left hand and shoved my right hand in his direction. The Senator took my hand and shook it. I was determined not to let go. "Let go," he said. "Let go," he said in louder, somewhat worried tone as the train just started to move. I could tell he was wondering if he should pull me aboard. Just at that time, I let go and jumped off. He won the Nebraska primary, but was assassinated a little over one month later.

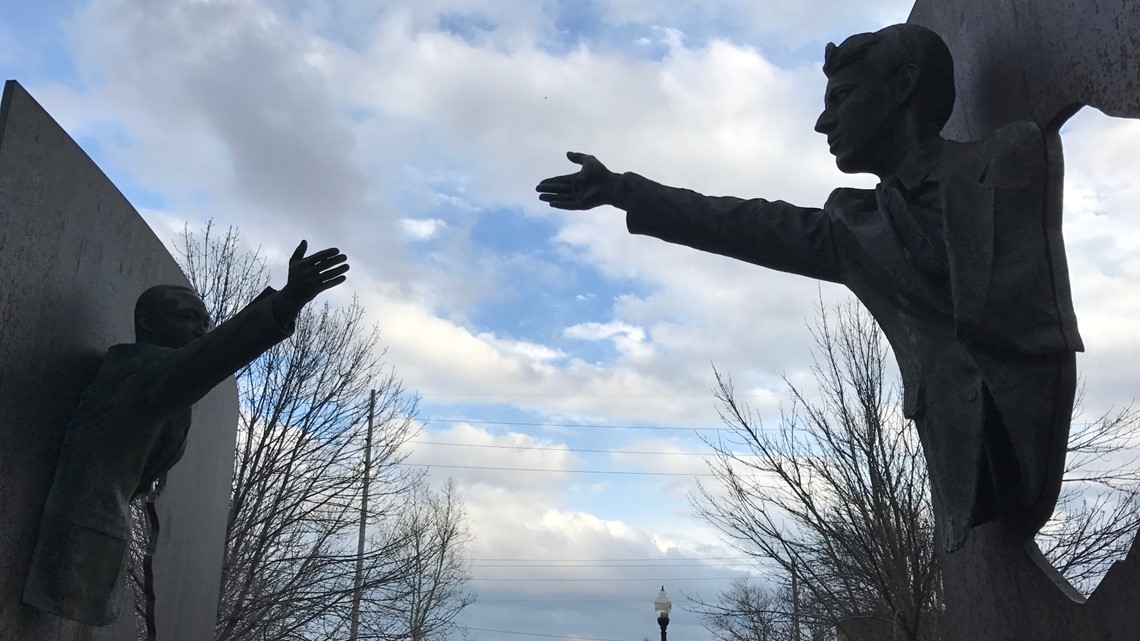

More than once I have visited the Martin Luther King park and looked at the statute of him with RFK. Their hands extended toward one another. It holds special significance to me. I long for the day when someone will be able to connect both of those hands.

So the man at the bus stop had it right. Thirty years later, I can still hear his words. "You ain't nobody." He was right. All the stories I have told over my 30 years at WTHR were never about me. They were all about you.

So now I end with a line I heard Garrison Keillor say when he retired: "I am not leaving you. I am joining you."

On Kevin's last day at WTHR, he joined Scott Swan on Facebook live to say goodbye.

RELATED: 2017 Year in Review: Only in Indiana