INDIANAPOLIS (Statehouse File) – High school senior Jadyn Rudd was born legally blind and was in second grade before her family learned she is deaf in her right ear and hearing impaired in her left.

Despite her challenges throughout public school, Rudd refuses to think of herself as different from any other high school student.

“I don’t look at hearing impairment and vision impairment as a disability. A disability is when you can’t actually walk on your own two feet or advocate for yourself in some sort of way,” Rudd said.

Rudd attended a public school throughout elementary school and junior high and then went to Madison Consolidated High School. After three weeks at her new school she transferred to Indiana School for the Blind and Visually Impaired on North College Ave. in Indianapolis.

Although Rudd lives closer to Kentucky’s school for the blind, she chose Indiana’s school.

“No offense, Indiana’s school is better. Not to mention we compete with them in sports,” Rudd said.

In 2014, there were more than 66,300 blind people living in Indiana, according to the National Federation of the Blind statistics. Of that number, there are about 450 children and young adults from preschool until age 22 who attend the Indiana School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, one of the largest such schools in the country.

The school looks like a college campus with the tall brick tower and long connected hallways. The building, with its aging and weathered limestone exterior, was built more than a century ago. Carved stone railings line stairways covered with jade-colored tiles.

What sets the campus apart from any other school are the different chimes that play each hour to let students know that it is time for the next class.

The Indiana School for the Blind and Visually Impaired provides the opportunity for students like Jadyn Rudd to be successful and grow to be as independent as possible. (TheStatehouseFile.com Photo/Nicole Hernandez)

The Indiana School for the Blind and Visually Impaired provides the opportunity for students like Jadyn Rudd to be successful and grow to be as independent as possible. (TheStatehouseFile.com Photo/Nicole Hernandez)Not only does this school specialize in serving the blind and visually impaired community, it is nationally and internationally recognized for its work.

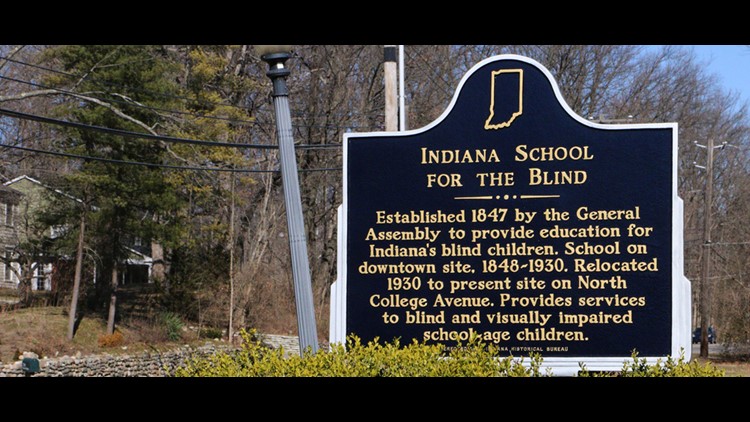

The school was founded in 1847 when the Indiana General Assembly was petitioned about the need for a school to serve the state’s blind students.

The original school was built on the site of the War Memorial in downtown Indianapolis and had just nine students.

Since then, the school has seen students from all over the state, the country and even from around the world through their exchange student program. One recent student had traveled from India to attend the School for the Blind.

“The biggest impact I see is how much students progress both academically and socially. I’m frequently told by parents that they are very impressed when their children come home after an initial stay with all the things that they can do that they didn’t know that they could do,” Superintendent James Durst said.

The school also provides the opportunity for students to be successful, grow to be as independent as possible and maximize their skills where they might not get those same opportunities in a regular public school. The Indiana School for the Blind and Visually Impaired (ISBVI) provides small class sizes so the students get the individual attention they need and they can get involved in sports and extracurricular activities that may not have the opportunity to otherwise.

The school operates just like any other public school in Indiana and must meet the same core academic standards. The only difference is the additional courses specifically catered to blind students, like braille courses.

Rudd has taken advantage of the opportunities that she has at the school by getting involved in cheerleading, track and field and public speaking. She even leads meetings and projects with the community through her position as student council president.

“In public school, it seemed unfair because everyone could do this except me, but here it’s everyone does the same,” Rudd said.

ISBVI has strong state and legislative support with 97 percent of the funding coming from the state, two percent from donations and one percent from federal grants.

The Indiana School for the Blind and Visually Impaired re-located to this building in the early 1920s. The iconic tower was originally a working water tower. (TheStatehouseFile.com Photo/Nicole Hernandez)

The Indiana School for the Blind and Visually Impaired re-located to this building in the early 1920s. The iconic tower was originally a working water tower. (TheStatehouseFile.com Photo/Nicole Hernandez)The school also receives financial help from the Indiana Blind Children’s foundation, which was established in order to help provide the school with the technology and programs that they need and use today.

“It is extremely expensive to educate children with visual impairments or children with any disability, and so the state provides a wonderful budget to the school,” Alvarado said. “But if we can provide the additional support and make sure that the kids are able to participate in after school activities, to be out in the community a bit more, or have the assistive technology they need to learn and grow, then I think we are an extremely important piece of the overall system.”

The school also has a dedicated, committed and specially trained faculty and staff.

Horticulture Teacher and Landscape Consultant Elizabeth Garvey is in her 28th year of working at the school.

Garvey first learned about the school because her husband is visually impaired, and she has always been interested in working with special populations. In 2013, Garvey was working toward her master’s degree and focused on the school for the blind.

But the campus is what really drew her to the school.

The school has a beautiful campus, but when Garvey visited, they didn’t have anyone to maintain the landscaping. That’s where Garvey came in. As she worked on her thesis, she was offered a position to start her own program because of her landscaping experience and interest in horticulture.

Through her research and thesis project, she created a plan for an accessible outdoor adventure trail that actually ended up being built with a donation from David Letterman. Garvey wanted the school to have a safe way for the students to access the neighborhood from the Monon Trail.

For Rudd, Garvey’s horticulture class is one of her favorites.

“We get to play with dirt and soil and I think that’s one of everyone’s favorite part,” said Rudd.

In Garvey’s horticulture class, students are able to grow plants and observe them by working with their hands. Students enjoy it because it’s hands-on and the students get to learn about the importance of nature.

“I’m just lucky that I get to teach them about something that I’m passionate about,” Garvey said. “The more I learn, the more I realize I don’t know. It’s very humbling. You’re always learning something new. The students can teach you new things, just about being a better teacher, about life and their challenges. I think there’s just always something new to learn.”

As for Rudd, the experiences at the school have equipped her to continue learning and pursuing her goals. Her next step after graduation is to attend Ivy Tech to get a general studies diploma and then decide what’s next, whether to pursue a career in counseling, therapy or psychology.

“Just because I’m visually impaired doesn’t mean that I’m any different than you and just like you,” Rudd said. “People like us can do anything we put our mind to.”

This content was reproduced from TheStatehouseFile.com, a news service powered by Franklin College.