WABASH, Ind. — As a coalition advocating for people impacted by the residential school system moves to digitize some 20,000 archival pages related to Quaker-operated institutions, tribal and state leaders have started initial conversations about what it would take to repatriate several Oglala Sioux children who lost their lives at one such institution in Indiana.

White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute operated for 12 years in Wabash from 1882 to 1895. The graves of at least 13 children remain buried on the property. Moses Two Bulls, 16; Rosa Fast Horse, 14; Carrie Noflesh, 13; and Theresa Bissonette, possibly 18; are marked in school records as being from Pine Ridge Reservation and were Oglala Sioux.

Fifth Member Justin Pourier, and other Oglala Sioux tribe members who make up the Tribal Historical Preservation Office Advisory Committee tasked with coordinating repatriation efforts of children back to Pine Ridge, met with representatives from White's Residential and Family Services and Indiana Department of Natural Resources leaders back in April.

"We spent like a whole day there, walking in the area where the graves are at. I did talk to one school official and told them, you know, this is evident that five of the students were Oglala because they have last names that are still here used on the reservation with families. So, we told them we would be working towards returning those students," Pourier said.

While Pourier had heard from older people at Pine Ridge that many children were sent to White's, and that information had been passed along throughout the community, they did not know about the existence of actual gravesites until being notified by Indiana DNR.

Throughout a 13-hour drive from Pine Ridge Reservation to Wabash, Pourier said he considered what the journey must have felt like for children who were often coerced into attending the school and arrived in Indiana with no family.

"You go back to all the feelings of those students — what they had to do when they left, and where they were sent from their homes. All the way out to an unknown country to try to learn how the white man wants us to live," Pourier said.

A company from Michigan provided ground-penetrating radar services, so THPO and Indiana DNR officials could confirm the bodies of children were actually at the site on White's and had not been moved from another location.

"One question we had might have been, you know, maybe the graves might have been moved from somewhere prior and are just the headstones removed? And the graves could have been somewhere else. But the studies show that the graves are marked correctly with the headstones," Pourier said.

When Indiana DNR provided student enrollment records from 1882 to 1895 to THPO, the names of family members stood out. Some relatives of children who died, like Elvyn "Doug" Bissonette, 72, saw their own name listed among those who died.

Theresa Bissonette was the sister of his great-grandfather, Hubert.

"She comes from a large family. Like, 18 children. Joseph Bissonette and Nellie Plenty Brothers had 19 children," Bissonette said.

The repatriation at White's would not mark the first one in Indiana the Oglala Sioux were involved with.

Many of the same people involved with the repatriation of children's remains at White's pushed hard for the return of human remains found in possession of amateur archaeologist Don Miller, who hoarded some 42,000 human remains and cultural artifacts in his Waldron, Indiana, farmhouse for decades.

Those human remains and items were stolen from across the world, but Miller was noted to have a "special passion" for stolen "Native American cultural goods" specifically, according to an FBI report. Five hundred sets of human remains found in Miller's collection had been looted from Native American burial grounds, according to the FBI. The FBI took control of the items in 2014. It was the largest single recovery of cultural property in FBI history.

When Tribal Historical Preservation Office members drove to Indianapolis in 2019 to reclaim the stolen remains of relatives and cultural artifacts, it marked an emotional end to a nine-year effort. Pourier recalled the deep sadness felt during that process.

"A handful of us just felt the energy, the uneasiness. And then, we did our prayers, and we sang our songs, and after that, everything had calmed down. So, it's very touchy," Pourier said. "There's, of course, times standing in that building that some of us shed tears. It's not good. It's not an easy job, I guess."

As with their involvement in the Miller case, Pourier said it is vital the Oglala Sioux or other impacted tribes are involved in the processes necessary for returning the children's bodies back home. Whenever the time for repatriation comes, it will mark the first time children who lost their lives inside a brutally oppressive system will be in the presence of relatives and kin.

"You have to say prayers and give a blessing, make sure they come back OK because their spirit has been there all this time. And they probably wanted to come back, but wasn't able to when they passed away. When they passed away, there were no family members around or anything like that," Bissonette said.

The Oglala Sioux will oversee essential parts of repatriation in a way nobody else can.

"It's unnatural to remove someone from a grave. But, you know, our spiritual advisors and our medicine men are saying there's protocols and special prayers that need to go into something like that to protect whoever's doing that type of work. And to make sure that, you know, the spirit of that person is dealt with, are satisfied. It's a big prayerful thing, that we got to do that," Pourier said.

As THPO works to coordinate a repatriation at White's, a new push from a national organization could lead to repatriations at other Quaker-led residential schools across the country. In August, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition announced they will move to digitize some 20,000 archival pages related to Quaker-operated boarding schools with a grant of $124,311 from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.

Names or information that come from the public release of residential school records could prove invaluable for tribes working to find or repatriate children who died across the United States. Although the THPO Advisory Committee is handling the repatriation of Oglala Sioux children, they are also working hard to notify other tribes about the existence of children who died at White's. THPO has reached out to multiple tribes and entities trying to find relatives of Reba White, a 5-year-old from Crow Creek Reservation, who is the youngest person on record at the White's gravesite.

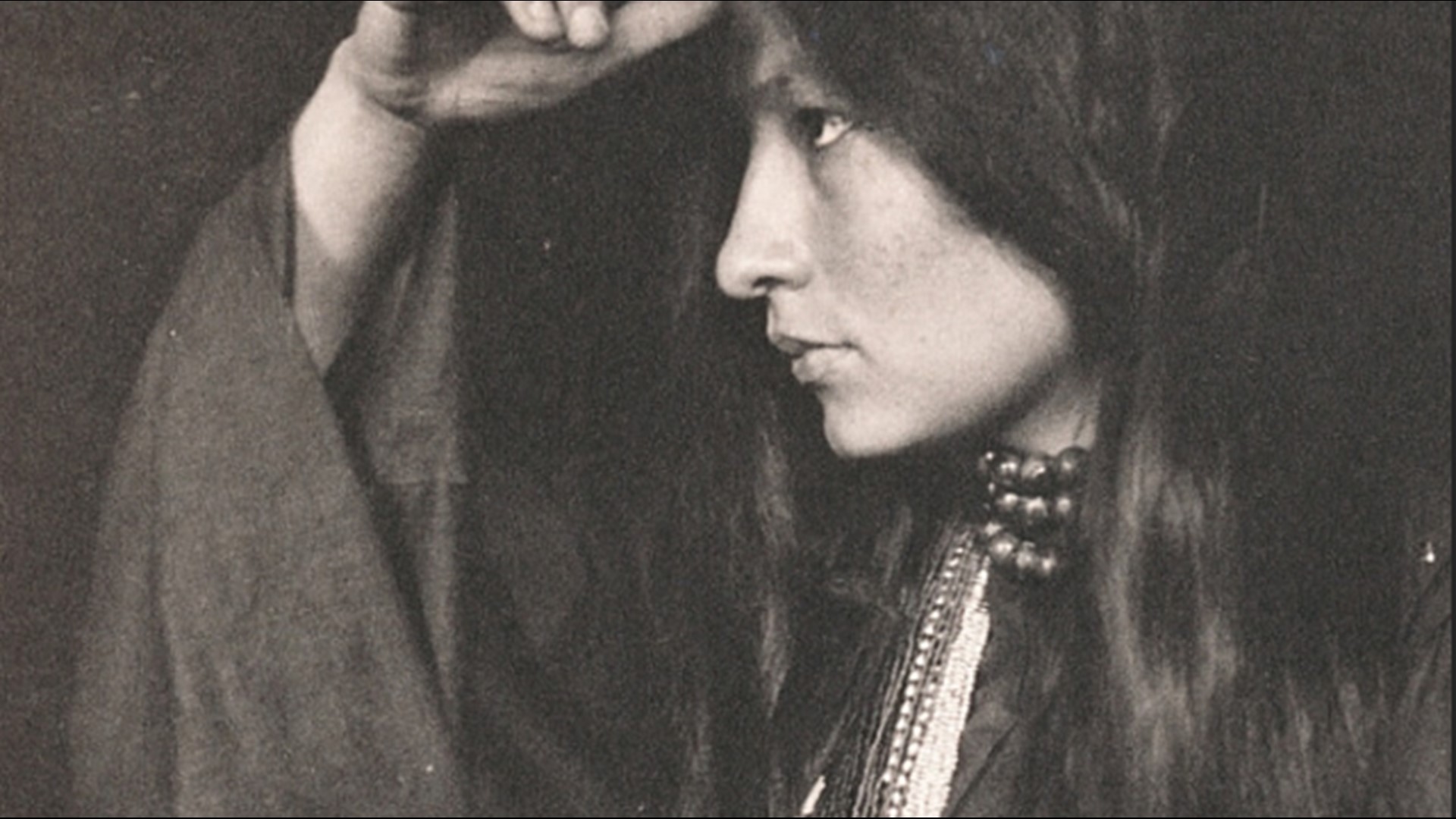

In 2021, 13News obtained some records from White's Residential and Services, which included student attendance records. Save for an autobiography from renowned Dakota author Zitkála-Šá that recounted firsthand abuse she experienced at the school, there is likely a large cache of information missing from public record about what students experienced firsthand there.

She once wrote about neglect endured by her friend and fellow student even as she was dying.

"At her deathbed I stood weeping, as the paleface woman sat near her moistening the dry lips….I grew bitter, and censured the woman for cruel neglect of our physical ills," Zitkála-Šá wrote.

Quaker missionaries established White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute in Wabash three years after Carlisle Indian Industrial School was founded, and was modeled on the same principles of cultural genocide and brutalization of children.

THPO is also working to repatriate three children from Carlisle, in addition to the students at White's.

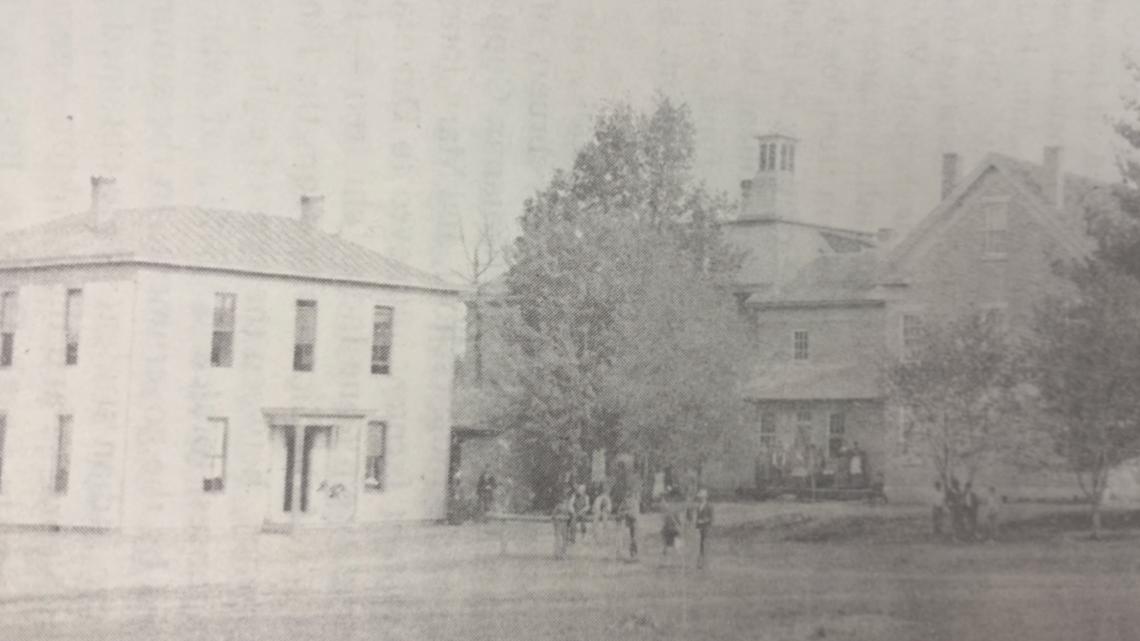

School archival records provided to 13News from White's Residential and Family Services, which still exists on the same grounds today as a Christian-based residential school affiliated with the Indiana Department of Child Services, show at least 200 Native children would attend White's between 1883 and 1895.

Enrollment entry rosters from 1883 to 1891 show Sac and Fox, Potawatomi, Modoc, Seneca, Shawnee, Ottawa, Quapaw, Wyandotte and Cheyenne children were all in attendance at White's. Indiana DNR revealed in January 2023 that they found children from at least 40 tribes went to White's.

Few photographs are publicly available from White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute. 13News received reports that a Cincinnati-based art gallery called Cowan's Auctions once had a large collection of student photographs from White's. It was sold in 2003 for $4,600. However, the gallery told 13News they did not have information on who eventually bought the collection of photographs.

NABS said documents like student records and photographs related to Quaker-operated Indian boarding schools have been understudied because they are mostly kept in rural locations with limited access.

The coalition will collaborate with Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College and Quaker & Special Collections at Haverford College. Some 20,000 pages of enrollment papers, financial information, correspondence, administrative records and photographs will be scanned in the fall of 2023.

WTHR Documentary | The Brutal History of Native boarding schools in Indiana

Records range from 1852 and 1945, and include nine Quaker-operated Indian boarding schools throughout Kansas, Nebraska, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania and Indiana.

A community information session will be held with tribal communities to discuss project findings after the archives are digitized, according to NABS.

Archivists said the partnership was necessary to reveal the truth about Indian boarding schools in the United States.

“I hope this partnership opens the door for more discussion and understanding about religious institutions’ role in the operation of Indian boarding schools,” said Celia Caust-Ellenbogen, associate curator for Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, in a statement. “These records can inform us about the conditions in which Native students lived, how Quaker institutions were financed through the federal government, and reveal the motivations behind U.S. assimilation policy design.”

Records will be made publicly available in spring 2024 through a database called the National Indian Boarding School Digital Archive, or NIBSDA, which is set to launch later this year.

The project will also include the production of a video that shares oral histories from boarding school survivors and their families.

“The digitization of these collections will yield new research and narratives about the underexamined history of Quaker-operated Indian boarding schools,” said Sarah Horowitz, curator of Rare Books & Manuscripts and head of Quaker and special collections at Haverford College. “These records reveal storied experiences and information that is too often absent from the public record, but that are increasingly sought by historians of Native American and American history.”

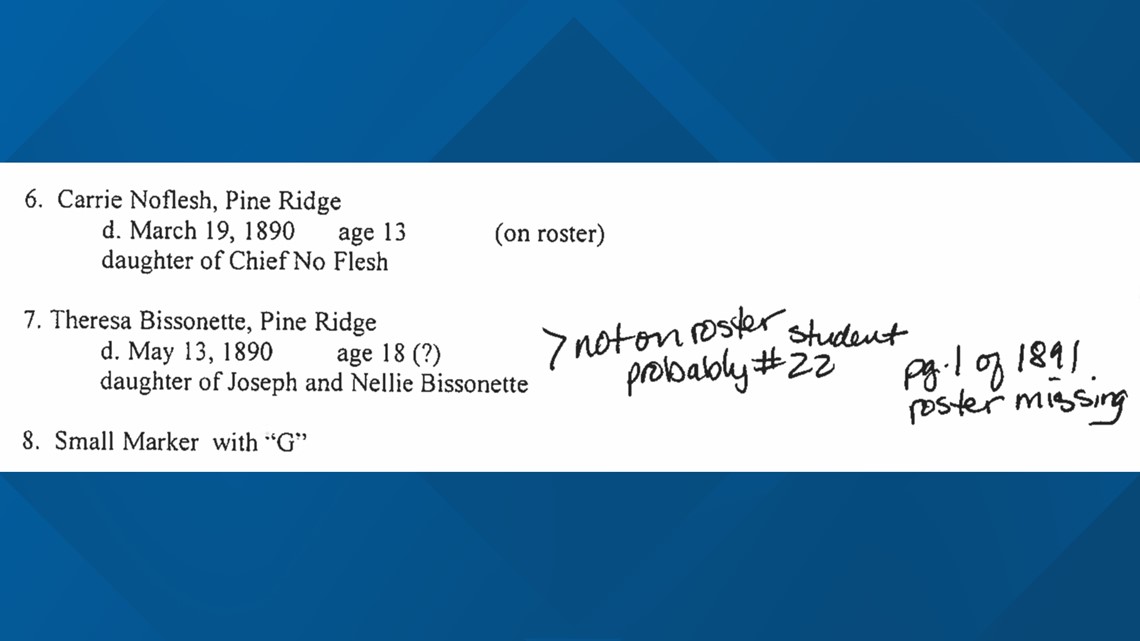

That could possibly include more information about White's, which may have a page missing from student enrollment records. In records, Theresa Bissonette's name has a (?) next to it with the note that reads: "Not on roster, probably student #22. pg. 1 of 1891 roster missing?"

Current records show the following children died at White's:

- Moses Two Bulls, 16, from Pine Ridge Reservation

- Rosa Fast Horse, 14, of Pine Ridge Reservation

- Reba White, 5, from Crow Creek Reservation

- Mary Trimmer, 12, from Santee Agency

- Carrie No Flesh, 13, from Pine Ridge Reservation

- Theresa Bissonette, around the age of 18, from Pine Ridge Reservation

- Siddie Long, 20, from Wyandotte

13News also located four graves with the inscription "White's Institute" at Friend's Cemetery in Noble Township, but could not verify dates on the stones or names of the deceased.

Indiana DNR declined multiple requests for comment regarding updates for the site at White's, which included questions about available funding for repatriation, a timeline for when repatriations could potentially take place, if the number of children buried at the site was more than indicated in school records, when research was conducted on the gravesites and how many families DNR had potentially reached out to.

This story was initially published on 2:49 p.m. on Aug. 28, 2023. A few hours after this story was published, at 4:06 p.m., a spokesperson with Indiana DNR said they had seen the story.

Indiana DNR sent 13News the following statement:

This spring, a private archaeology firm conducted a geophysical survey of the cemetery to identify potentially unmarked graves, with representatives from the Oglala Sioux and the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma in attendance.

The results of that survey have been shared directly with the tribes.

Any repatriation of the children buried in the cemetery would be a matter between the tribes and the property owner. DNR’s regulatory role in this situation would be to provide permitting for the disinterment of remains per the Indiana Historic Preservation and Archeology Act (IC 14-21).

Alternatively, the tribes and the property owner could follow the process set out in the Indiana General Cemetery Act (IC 23-14-57-5), which does not require permitting from DNR.

Pourier said Indiana DNR has been helpful and respectful throughout the process so far.

"They didn't have to go through the extent of survey that they did," Pourier said. "They were real respectful and professional, and they gave us time to do our prayers. And they gave us privacy to do what we had to do. The survey work was respectable, and the state people that were there, you know, observing. And I want to thank them for reaching out to us, and then going that step beyond to do all that."

While lack of funding could slow the timeline of repatriation, Pourier said the Oglala Sioux will be able to raise enough funds for those efforts separately from Indiana DNR.

"The problem with Wabash is that the state has said they have no funding to assist the tribe returning those students. So, we're gonna have to, first of all, get a date set. Then, we gotta get a budget, and then, we gotta go and try to raise the money to return those students. But as you know, if it comes down to it, the tribe will do everything they can to get our relative's home," Pourier said.

NABS declined request for comment at the time of publishing. 13News reached out to officials at White's, but did not hear back and have not heard back from the institution since the original report came out in April 2021.

White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute was one of two residential schools established in Indiana.

St. Joseph's Indian Normal School operated for six years in the late 1800s and was run by Catholic missionaries.