LAWRENCEBURG, Ind. — Over 45,0000 people are asking the Cincinnati Zoo to name a soon-to-be-born sloth in memory of Oliver Nicholson and to raise awareness about the rare syndrome that ultimately led to his death.

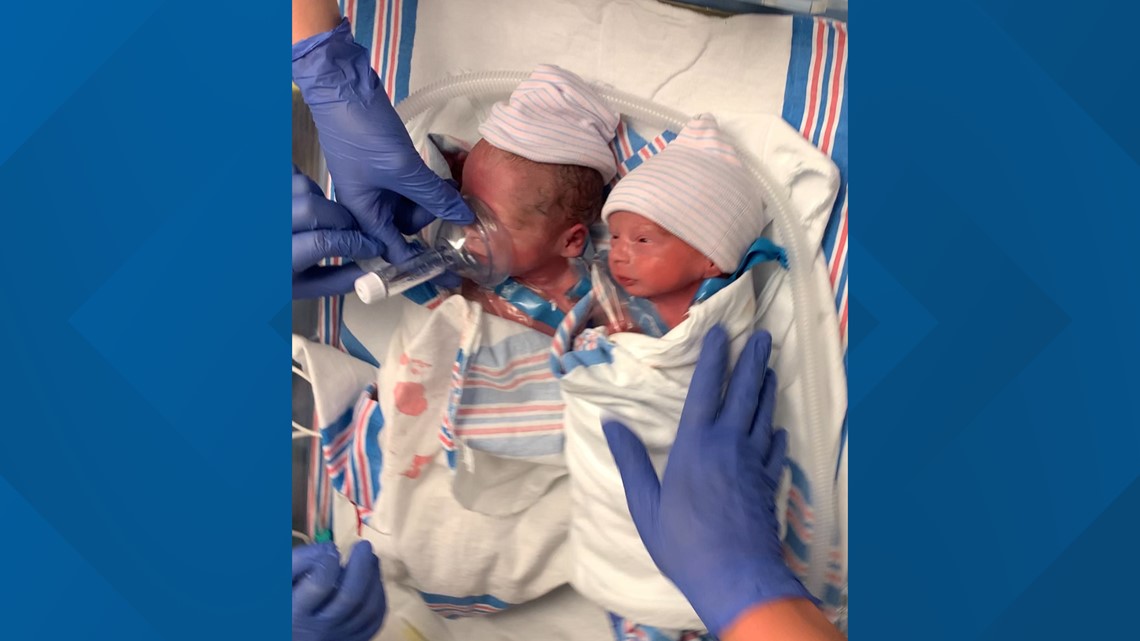

The twins are here

Since the moment he was born, Oliver Nicholson was not only a miracle but a fighter.

“Both of his vocal cords were paralyzed,” said Oliver’s mother, Alyssa Nicholson.

She said it wasn’t clear whether the paralysis was caused by having massive surgeries at only a few months old or if he was born that way.

“I had doctors tell me he’d never talk, others tell me he would only be able to whisper, and some who said no one should have told me any of that,” said Alyssa.

For about 10 months, “he would cry, and nothing would come out. It was the most horrible thing you could see. You think watching a child cry is horrible. But to see a child cry and nothing comes out is…,” she said pausing, "it’s not pleasant,” she said shaking her head as if remembering.

But during his 18 months on this Earth, Oliver did talk. And the three words he chose to share with this world were ‘Mama,’ ‘Dadda,’ and ‘Hi.’ Three words that sum up the bubbly, always-smiling toddler, who — within his tiny preemie frame — carried the might of giants.

“It was amazing to hear him say ‘Mama,’" said Alyssa. “It made me so overjoyed to hear him say it. I was so proud."

Oliver is synonymous with fighter. He fought to see this world.

“I was exactly 33 weeks, and my water broke,” said Alyssa.

“It was an emergency C-section,” said her husband, Alex. “They had done an ultrasound and Oliver wasn’t moving. He hadn’t moved in 30 minutes.”

“They had kinda warned me on the side [away from Alyssa] that Oliver might not be alive,” said Alex.

But like a true Nicholson, Oliver, although 19% smaller than his twin, fought through.

“I remember the doctors, they said, ‘Oh look at you, you just want to see your new world, don’t you,’” said Alyssa. That was the first time the mother said she began crying with joy that both of her baby boys were here.

Atticus, although a preemie, was healthy. He spent two months in the NICU under a blue light and was discharged and cleared to go home.

Oliver was born with one kidney, heart issues and his esophagus was not connected to his stomach. At three months old, he underwent his first of three major surgeries, some lasting as long as 12 hours. He spent the first five months of his life in the NICU at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

Alyssa said her husband was "in shock" when Oliver was born.

“He said, ‘He doesn’t have arms.' And I said, ‘It’s fine. He’s alive. It’s fine,’” said Alyssa, smiling.

Bonding

Some mothers feel an initial bond with their children, others take some time. For Alyssa, it was instant.

“I felt an instant bond with both of them,” said Alyssa. “I was never scared. I have fear now with my new pregnancy because of losing Oliver, because you now live in this world of reality where things don’t always go the way you want them to."

Alex said he formed a very strong bond with Oliver. He said the Children’s Hospital was right near his work so while Alyssa was taking care of Atticus at home and working, Alex was able to make more visits to the hospital.

Alyssa described that time as “very difficult” and said she got her strength from the twins.

“Oliver and I were very close,” said Alex. “But I will admit not at first. It all kinda scared me at first. It was overwhelming. I didn’t know how to process it all to a degree."

“When he was in the NICU, they encouraged us to hold him for skin-to-skin contact, and for the first week or so, I was hesitant but after that, I formed a very strong bond with him,” Alex added.

Oli’s diagnosis

Doctors diagnosed Oliver with VACTERL (also known as VATER association, VACTER association or VACTERLS association). It’s an acronym, each letter represents a part of the human anatomy.

The cause of VACTERL is still “not well understood,” and no specific genetic or chromosome has been identified. However, experts say, some possible genetic and environmental influences are being studied. The characteristics of VACTERL are also different in each individual and “unless there are severe defects, babies with VACTERL association do well and can lead normal, productive lives.”

A diagnosis is based on the presence of clinical features in at least three areas:

- (V) = (costo-) vertebral abnormalities

- (A) = anal atresia

- (C) = cardiac (heart) defects

- (TE) = tracheal-esophageal abnormalities, including atresia, stenosis and fistula

- (R) = renal (kidney) and radial abnormalities

- (L) = limb abnormalities

- (S) = single umbilical artery

“I think Oliver had all of them, except the ‘V’ we’re not sure of, we hadn’t confirmed it,” said Alex.

Oliver had to see a specialist for each affected area.

“I think we’ve been to every floor of the Children’s Hospital,” said Alex.

Alex and Alyssa said getting a diagnosis for the rare syndrome wasn’t easy. They had googled symptoms, and their research leads them to read up on VACTERL. They remember seeing it written in medical notes, and after which, asked the doctor about it.

But for some reason, it wasn’t as clear-cut as "the diagnosis for Oliver is VACTERL." The Nicholsons say they hope raising awareness about the syndrome will make it easier for other parents.

'Mr. Sloth'

Oliver being diagnosed with VACTERL meant a lot of hospital visits, and "Mr. Sloth," a toy given to him by his father, was there to help him get through.

“We never posed him in photos,” said Alex.

“He would just snuggle it [Mr. Sloth] and sleep with it every night,” said Alyssa. “And people just started getting him sloth gifts."

If you look closely throughout the Nicholson household, sloth items can be found sprinkled throughout, from pillows to painting and, in the children’s play area, stuffed animals.

Like a Nicholson

The Nicholsons said they were aware of the life-threatening risks Oliver faced as he prepared for three major surgeries. But these surgeries were necessary to safe his life. Oliver faced all three of them like a champ.

“Even when he was poked and prodded, he didn’t like that very much, but he would smile as soon as it was over,” said Alex.

Alyssa said she remembers Oliver dancing happily. Alex said Oliver’s last two surgeries were about 12 hours, the first of the two was longer than expected, but the second surgery was supposed to take that long.

Doctors came out after the second surgery, Oliver’s third since he was born, and began to brief them on the list of options they had for trying to attach Oli’s stomach to his esophagus.

After 12 hours of anxiously waiting, Alex had to interrupt the medical team to ask them if his son was OK.

Oliver had made it through his last big surgery. His stomach and esophagus were connected, and the Nicholsons said they were told they were now in the clear.

“He did it and they were successful. It’s over,” said Alex. “He’ll always have struggles and have therapies, but Oliver will be there with us,” he added.

“We were just overjoyed that we didn’t have to legitimately worry that we were going to lose him,” said Alex.

“He was stable,” said Alex firmly, but less than a second after the word “stable” left his lips was the look of reality still settling in.

About five weeks later, there were complications during a routine medical procedure. Oliver was having a balloon slightly inflated down his digestive track to make sure that the path that was created remained clear and didn’t close up.

During the surgery, Alex was called to the same room where he had received wonderful news a few weeks earlier. But this time, it wasn’t just the doctor in the room. A priest was accompanying the doctor who had been treating Oliver since he first came to Children’s Hospital.

A legacy is born

“He [the doctor] said, 'We’re doing everything we can but I think we’re going to lose Oliver,'” said Alex.

Alex said he called his wife, and she rushed over to the hospital. Oliver’s parents were by his side, keeping a promise they had made to him early on.

“If he’s going to go through it, we’re going to be there right by his side and go through it with him,” said Alex. He said he would deal with the trauma later, but for now, it was important to be there for their son and to comfort his soul. Alex and Alyssa are Nicholsons after all.

Atticus seems too young to truly comprehend his twin is gone, or maybe he still remembers what existed before. The Nicholsons say “there are signs.”

“Atticus will ask to crawl into Oliver’s crib,” said Alex.

The twins have many double gifts or items. Atticus will ask for the version that belonged to his twin.

That bond is one that only twins can understand, especially because the boys spent many of their first few months on Earth apart.

Alex said being a parent to Atticus and his teenage son, Benjamin, while still mourning Oliver is difficult.

“I’m still working on that, to be honest,” said Alex.

“Ben’s in high school now, so that’s a whole different dynamic as a teenager. And then there’s Atticus, and we’re expecting in December,” Alex added.

“When I wrote his eulogy, that’s one of the things I ended with. ‘I don’t know how I’ll carry on, but I’ll find a way for your mother and for your siblings,’” said Alex.

“It still doesn’t feel like it happened to me,” said Alyssa. “I was there, but I wasn’t there."

Alex described experiencing the same disassociation, a common trauma response, when his son was born and when he passed.

“You have to go to therapy, you have to talk about it,” said Alex. “There’s two extremes — there are people who curl up in a ball in their bed and just shut down, and then, there are the people who just block it out completely. But I don’t think either one of those are healthy. The trick is finding a way to find the middle,” said Alex.

“There’s no getting back to normal,” he added. "That doesn’t exist anymore. Normal was when Oliver was here ... It’s our new version of what life is."

“I was in shock for weeks,” said Alyssa. “But I remember at the visitation, it was the first time I felt like I was next to my son again."

Alex said friends and family came to her at the service and asked if she had seen that the Cincinnati Zoo posted that its sloth is pregnant.

They had posted about it on the very same day of Oliver's funeral. For the Nicholsons, it was a sign.

“That very same day," Alex said excitedly. “We found out it was a two-toed sloth. There are three-toed sloths and two-toed sloths. This is a two-toed sloth, and Oliver had his one arm with two fingers."

“There were just a lot of coincidences along the way,” said Alex.

It’s hard not to notice the joy entering and filling the Nicholsons living room as they begin to share the coincidences.

With encouragement from the community, the Nicholsons created a petition for the baby sloth at Cincinnati Zoo to be named after Oliver. They want to raise awareness about VACTERL and honor their son’s legacy.

So far, the petition has garnered over 45,000 signatures. The Nicholsons have continued to receive sloth gifts, from friends, families and even strangers.

Alex shared a drawing of Oliver with Mr. Sloth, “I don’t even know who sent this one,” he said with joy.

The Nicholsons say if the baby sloth were to be named after Oliver, it would be a beautiful and meaningful tribute, not just to Oliver but to all the families and individuals touched by VACTERL.

It would also raise awareness for a rare syndrome that would help others feel seen and no longer feel alone.

Individuals have already reached out to 13News, saying that they would travel to the Cincinnati Zoo to show their children who have VACTERL, Oliver the sloth.