INDIANAPOLIS (WTHR) - When the incoming Trump administration put out a call for applicants to take over as Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy late last year, a Marion County Superior Court judge knew just the guy for the job.

Himself.

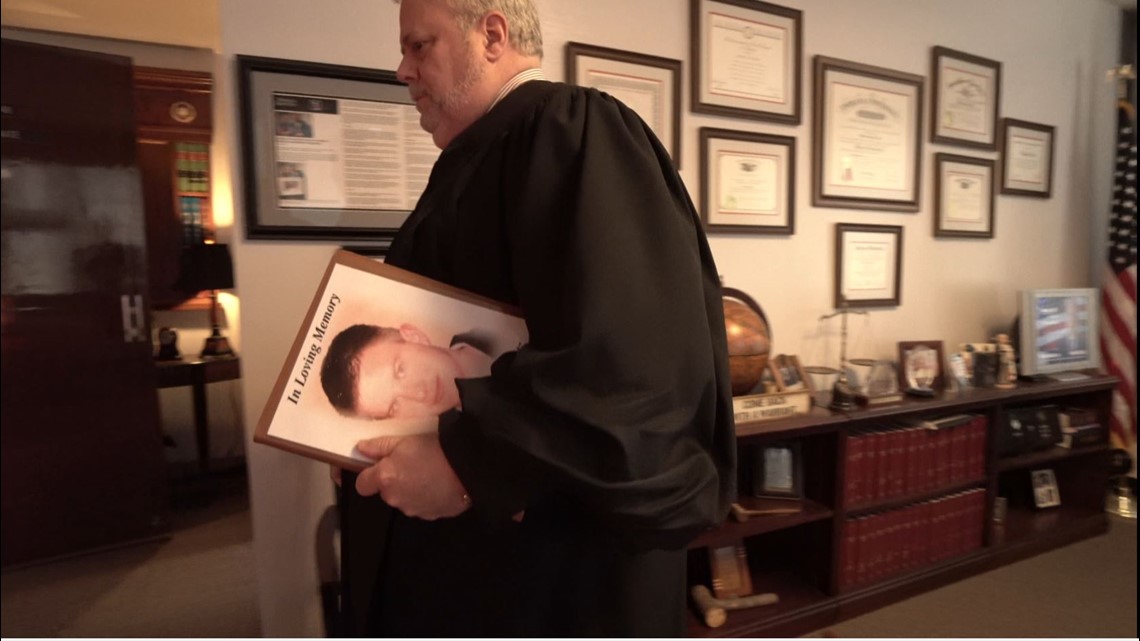

Judge William Nelson applied and was invited to the White House for an interview in July.

Judge Nelson has a compelling story to tell. It starts in 2008, when his 19-year-old step-son Bryan Fentz had a car accident. Fentz’ car slid off the road and he injured his arm. His mother Kristi took him to the doctor, who prescribed Vicodin for the pain. Kristi, a veteran medic who worked for IU Health, approved of the prescription and helped her son fill it, although she had some misgivings about the amount of the opioid drug her son received.

"He was prescribed 30 with one refill," she said. "That was 60 tablets. When you're first starting out that carried him through, taking a couple a day."

Shortly after that, his grandfather died and Bryan started mixing in Xanax to deal with the loss.

"Then he started doing Vicodin and Xanax and I thought it was over several months after that and that's when it started becoming he needed more and more and more," Kristi said.

It wasn't long before he went down the road of full-blown opioid addiction.

Rehab followed, and Bryan got clean for sixty days until he went back to the drugs in January of 2009. His mother found him in his room on her birthday, dead from an overdose.

But there was more.

It turns out that Bryan was aggressively stealing from his parents to pay for his $1,000 a week habit. He diverted their monthly mortgage payments and accessed their IRA accounts. The Nelsons didn't know anything about it until after Bryan died and their home as on the verge of a sheriff's sale. It took years to get their personal finances back on track.

Beyond the financial stress, their son's death brought grief, shame and frustration. It was not lost on Bryan's parents that his mother was a medical professional and his step-father was a judge who had been on the bench for nearly two decades at that point and handled drug-related cases on an almost daily basis. He did not hold back on punishment.

"I treated drug addicts like they were criminals," he said. Since his step-son's death, Judge Nelson has changed his approach. "I treat addiction for what it is," he says now. "It's a brain disease, it's an illness and I treat the people more so like they are people rather than criminals."

That's not to say he dismisses their crimes but he tried to temper punishment with treatment. "The climate of the stealing, the prostituting the burglarizing, those you deal with, but, you can't, we're not going to arrest our way out of this problem."

Shortly after losing Bryan, the Nelsons began to tell their story to high school groups and at community meetings around Central Indiana. They call if cathartic. The people they reach consider it life-saving. Several addicts have thanked them for saving their lives. Family members have come forward to thank them, too.

And in his courtroom, the loss of his step-son is never far from Judge Nelson's mind. He has a memorial picture of Bryan with him on the bench and shows it to young people who appear in his court for drug-related crimes. If their parents are there, he calls them forward too and gives them one good reason to try to get clean. "You'll wake up at your house. We spend Christmas staring at a headstone and a patch of grass," he tells them. "We spend birthdays and holidays doing that. Please don't make your parents do that."

Although he has not been told that he is out of the running, Judge Nelson is not expecting the Trump administration to call to offer him the drug czar job. He is encouraged, though, that the administration is talking about the opioid addiction problem and supporting the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act which would provide money to states for drug prevention and treatment . He believes the crisis is far from over and that it will take patience and persistence to solve the problem and will at least try to do his part from his courtroom at the City-County Building as drug-related cases come before him just about every day.