Too many to test: Deadlier, harder to spot poison pills flood Indiana

In Indiana, there were 2,812 overdose deaths in 2021 according to the Indiana Department of Health Drug Overdose dashboard.

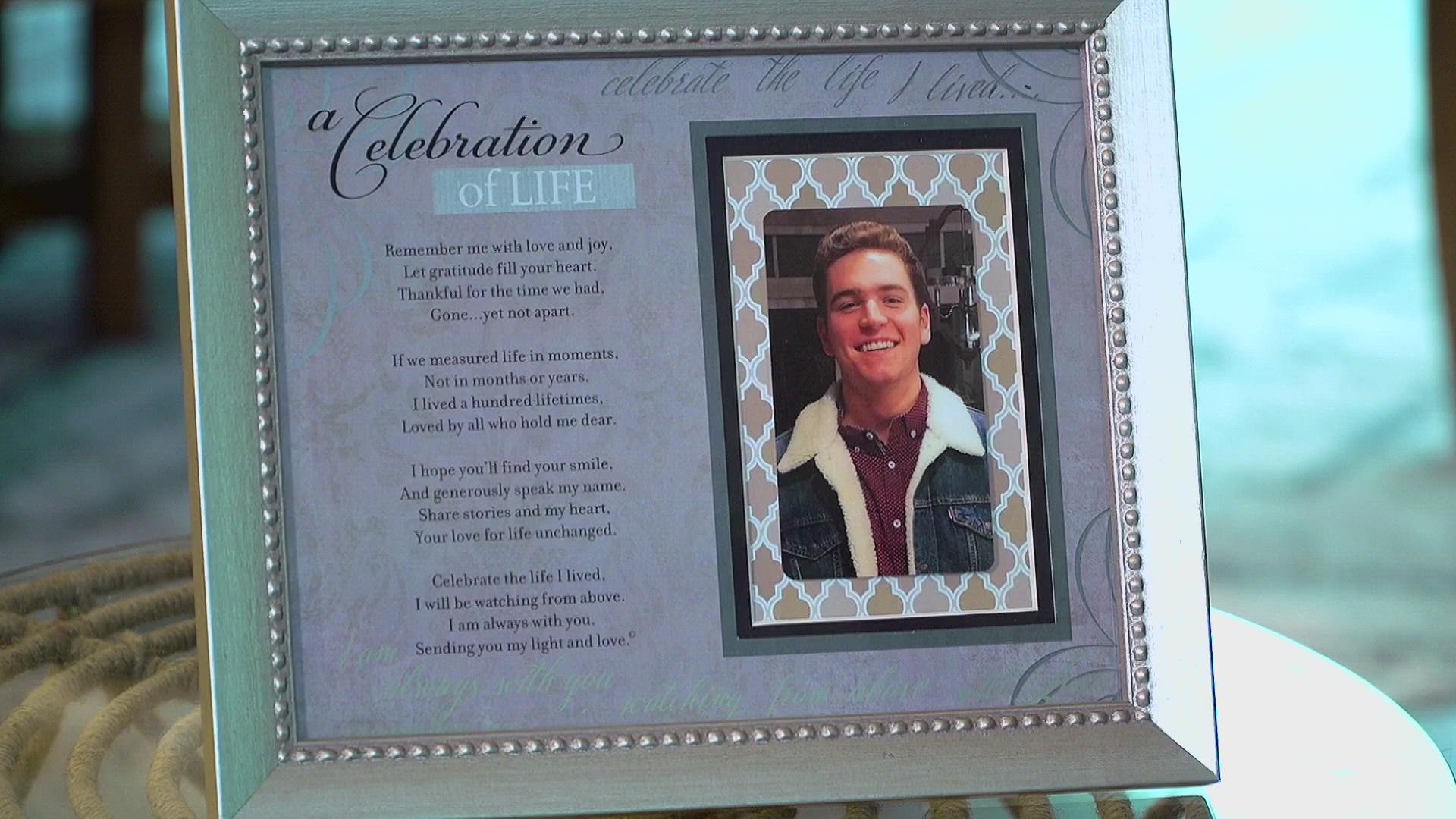

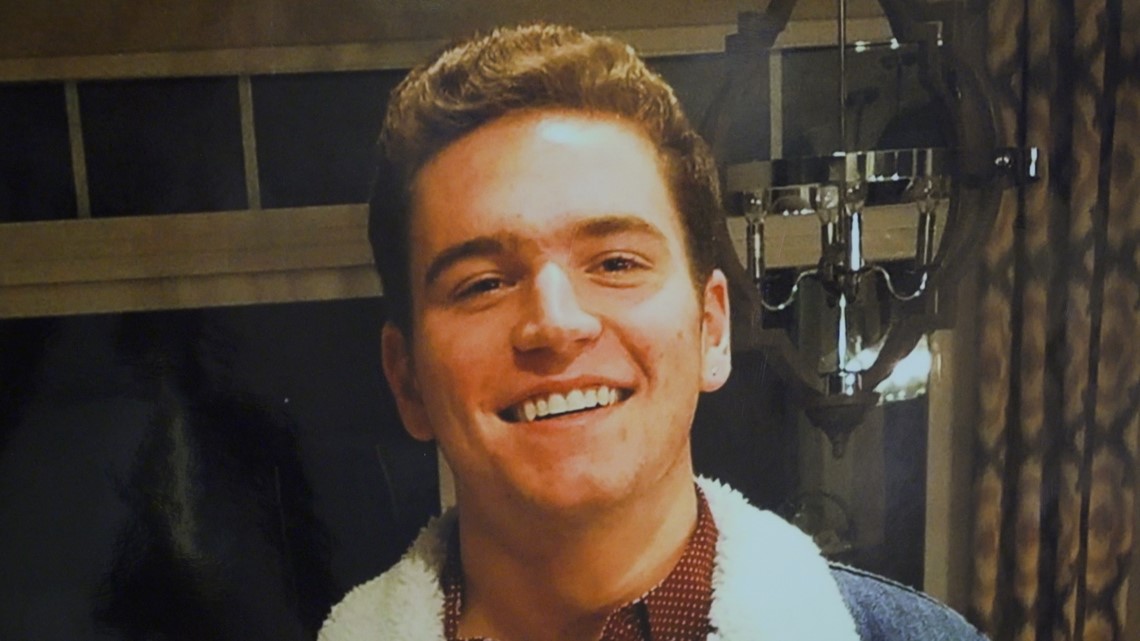

An evening knock at the door changed Dean Jeske’s life forever. On the other side, a state trooper with news from Bloomington where his youngest son, Peter, was attending Indiana University.

“I stood in the door for what felt like an hour,” Dean said.

Dean waited while the trooper went back to check some facts. He had the wrong name at first.

“I knew something was wrong, and my heart was pounding,” Dean said. “And he got out of his squad car and walked back up our driveway. And he said to me that thing that nobody ever wants to hear, which is, ‘I’m sorry to tell you sir, but your, your son was found dead in his apartment down at Indiana.'”

Dean said the news “demolished” his family. Weeks later, he would learn Peter died from fentanyl. It was a shock. The college student wasn’t known to do drugs. Dean started asking questions and now believes Peter didn’t overdose but instead was poisoned.

The Jeske’s believe the young man got a fake prescription pill – poison pill or “fentapil” – unaware that inside was enough fentanyl to kill.

“Peter made a mistake,” Dean said by getting and taking a non-prescribed pill. “But the mistake he made, and the mistake so many of these young people are making, is not a mistake that should cost them their life.”

Poison pills driving up death

These poison pills are killing people of all ages. Some have no idea they’re ingesting fentanyl. Instead, they’re being duped into thinking they’re getting a legitimate prescription pill like oxycodone, Adderall, Xanax or Percocet.

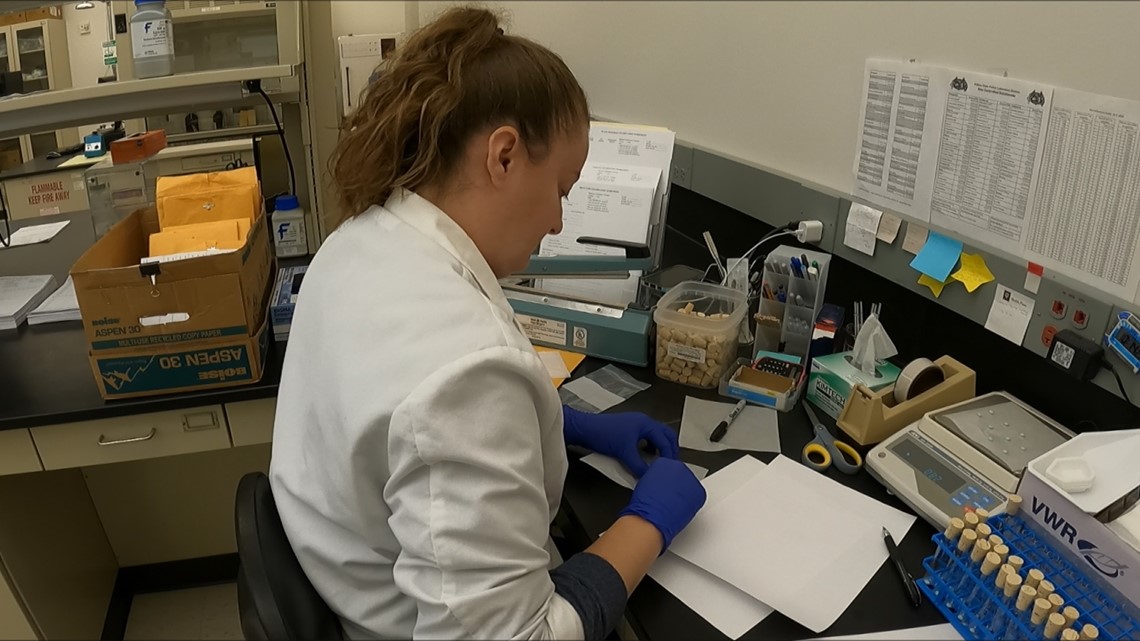

"They look nearly identical,” said Elizabeth Griffin, a drug unit supervisor at the Indiana State Police Laboratory. “Sometimes you can't tell the difference. They look just like them.”

Griffin is paid to distinguish real pills from the fake ones for criminal investigations.

She says inside many fake prescription pills she finds filler and fentanyl - meaning fentanyl is usually the only active ingredient.

“Three or four years ago we didn't see any fake tablets at all,” she said. “Basically, the tablets contained what they were marked to contain, but now, often, the tablets are containing something else."

She showed us some M-30 pills which are supposed to contain 30 milligrams of oxycodone. The lab tests showed there is zero oxycodone inside. That means the fake prescription pills are not laced with fentanyl. They’re just fentanyl pills.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration reports collecting 50.6 million fake pills in 2022 and about 20.4 million the year before. That’s just what DEA seizes – the total number of these poison pills on the streets is unknown.

It’s also hard to tell exactly how many people die solely from these pills. Still, the DEA says poison pills are considered the “primary driver” in drug poisonings. In 2021, the CDC reported 106,699 Americans, like Peter, died from drug poisoning nationwide.

In Indiana, there were 2,812 overdose deaths in 2021 according to the Indiana Department of Health Drug Overdose dashboard. Seventy-one percent of those deaths were due to synthetic opioids like fentanyl. In Marion County, the percentage is even higher. Officials say 80 percent of overdose deaths were due to synthetic opioids.

Too many pills to test

Monroe County Coroner Joani Stalcup says these pills are a major concern.

“Let's face it. You don't know what you're getting anymore," Stalcup said.

She said it’s hard to know how many fentanyl deaths are due to pills for a few reasons. Sometimes evidence is removed from a scene before a death investigation can begin. Another reason is even if a coroner or law enforcement officers seize pills on a scene, they’re not always tested.

Coroners across Indiana tell 13 Investigates, for the most part, only pills connected to a criminal investigation are tested. The reason is simple; there are not enough resources.

For years, a backlog of drug cases have stretched the resources of the Indiana State Police Laboratory and other labs. Griffin told 13 Investigates in December, her team is about eight months behind. As a result, ISP must send some samples out of state for testing.

Griffin says her team must be selective about what they test in-house. Right now, she is handling about 50 potential poison pill cases a month. While the state is building new facilities and hiring more forensic scientists to help with the backlog, Griffin says she doubts the issue will ever go away completely.

“I don’t think our backlog will ever be eliminated,” she said. “The cases submitted to us continue to grow. So every year it gets bigger. Before, we would never see a month where we got over 1,000 cases a month. And then we got used to over 1,200 cases a month. And now we have months where we have over 1,600 cases in a single month.”

"One Pill Can Kill"

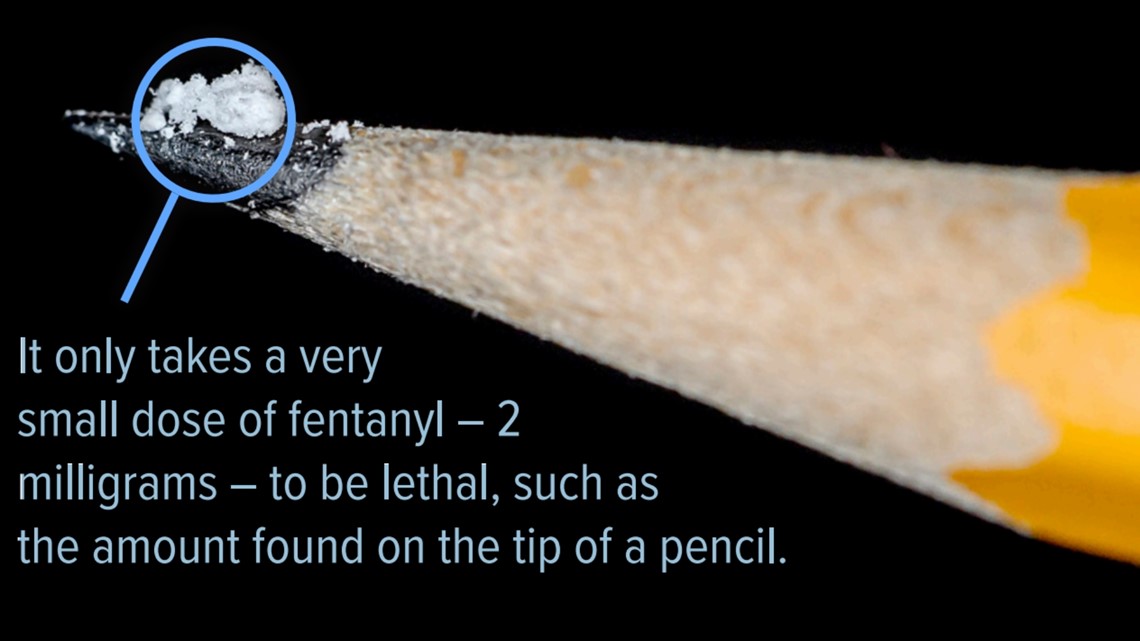

As the number of fentanyl cases skyrocketed, the DEA started the “One Pill Can Kill” campaign to help educate the public that more than 100,000 people are dying each year from drug poisonings.

13 Investigates spoke with coroners around the state as well as national drug experts. No one knows the total number of deaths from poison pills, but the experts agree - the majority of overdose cases are due to fentanyl.

The DEA urges parents to talk to their kids. It's public awareness campaign includes pictures of real and fake pills. The DEA website also has information to decode what emojis mean and how young people are using them to buy pills. Social media is one way criminal drug networks get out their product. The DEA reports finding illegal activity on Snapchat, Facebook Messenger, Instagram, Facebook, TikTok and even YouTube.

The administration is encouraging families to discuss the fact that only a small dose of fentanyl, 2 milligrams can kill – the same amount that can fit on the tip of a pencil.

Fentanyl can cause several physical and mental side effects including confusion, drowsiness, dizziness, changes in pupil size and respiratory failure that can lead to death.

Jeske knows social media is where young people are getting pills from dealers and sometimes even friends. He thinks many of them believe popping pills is relatively safe. It doesn't have the stigma of drugs like methamphetamine and heroin.

For that reason, he’s created a presentation and goes to speak at schools and other groups of teenagers and young people.

“I tell people all the time, 'I love to talk about how Peter lived,'” he said. “But it’s still a challenge to talk about how he died.”

“I do it because I want Peter to be proud of me,” Jeske said. “I’m pretty sure that this is what he’d want me to be doing.”

He also does it to warn and to protect other families.

“If I can just get to one young person or one parent who can then talk to their child about this and save one life...then it’s all worth it,” he said.

Jeske was inspired to act after talking to other families. He met a couple that lost a son and started the nonprofit Song For Charlie. The group's mission is to spread the word about fake pills.

Fighting with law and tech

While efforts to educate are underway, the federal government is also looking for new ways to stop the dissemination of these pills.

U.S. officials know the pills’ ingredients often originate in Asia. U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Indiana Zachary Myers told 13 Investigates the long journey to Indiana often begins in places like India and China.

“They’re being shipped to Mexico where super labs, controlled by one of two large Mexican drug cartels are taking these chemicals and synthesizing them into powders or into pills and shipping those across the border," Myers said.

Here in Indiana, his office tries to prosecute fentanyl and poison pill dealers. The office reported 25 people were charged and 23 were convicted in 2022 for fentanyl-related cases.

13News’ sister station in Tampa went to the U.S., Mexico border to see brand new technology in place to help stop illicit materials from crossing onto American soil.

A new multi-energy portal machine is now at the World Trade Bridge port of entry in Laredo, Texas. The machine uses multi-energy technology or X-rays to look inside unloaded trailers – like the security check system used at airports across the country.

“When the driver passes through the MEP, the low dosage of energy is on the driver,” said Assistant Port Director Javier Vasquez with U.S. Customs and Border Protection. “The high energy is on the trailer itself. We have shipments of machinery, so for steel items, we need something that can penetrate steel and look inside. This high-energy we can see what’s inside."

A group of agents monitor the images scanned by the MEP system.

It’s possibly a step in the right direction, but a small one. There are 50 crossings along the southern border but only two machines – one in Laredo and the other in Brownsville, Texas. The U.S. has a $480 million dollar contract to integrate the systems at other sites.

They are part of an evolving effort to stop poison pills from getting into the hands of other young people like Peter. A young man his father describes as smart, handsome and with his whole life ahead of him.

“He was really funny,” Jeske said. “Which was my favorite thing about him.”

Peter's father still chuckles remembering some of his jokes. Jeske shared how when he was driving down I-65 to retrieve Peter’s remains a joke about wind turbines came to mind.

“In my head, I can hear Peter saying, ‘Hey, look dad! Corn fans,’” Jeske said. “And it just sort of made me...it made me chuckle.”

He told his wife and other sons.

“Even in the most somber, most devastating moment there was Peter in my ear, kind of making me smile,” Jeske said.

A smile that takes a little longer to come now that Peter’s gone.