INDIANAPOLIS — Even before absentee ballots hit mailboxes and early voting centers open, there’s already a sense this election is unlike any other.

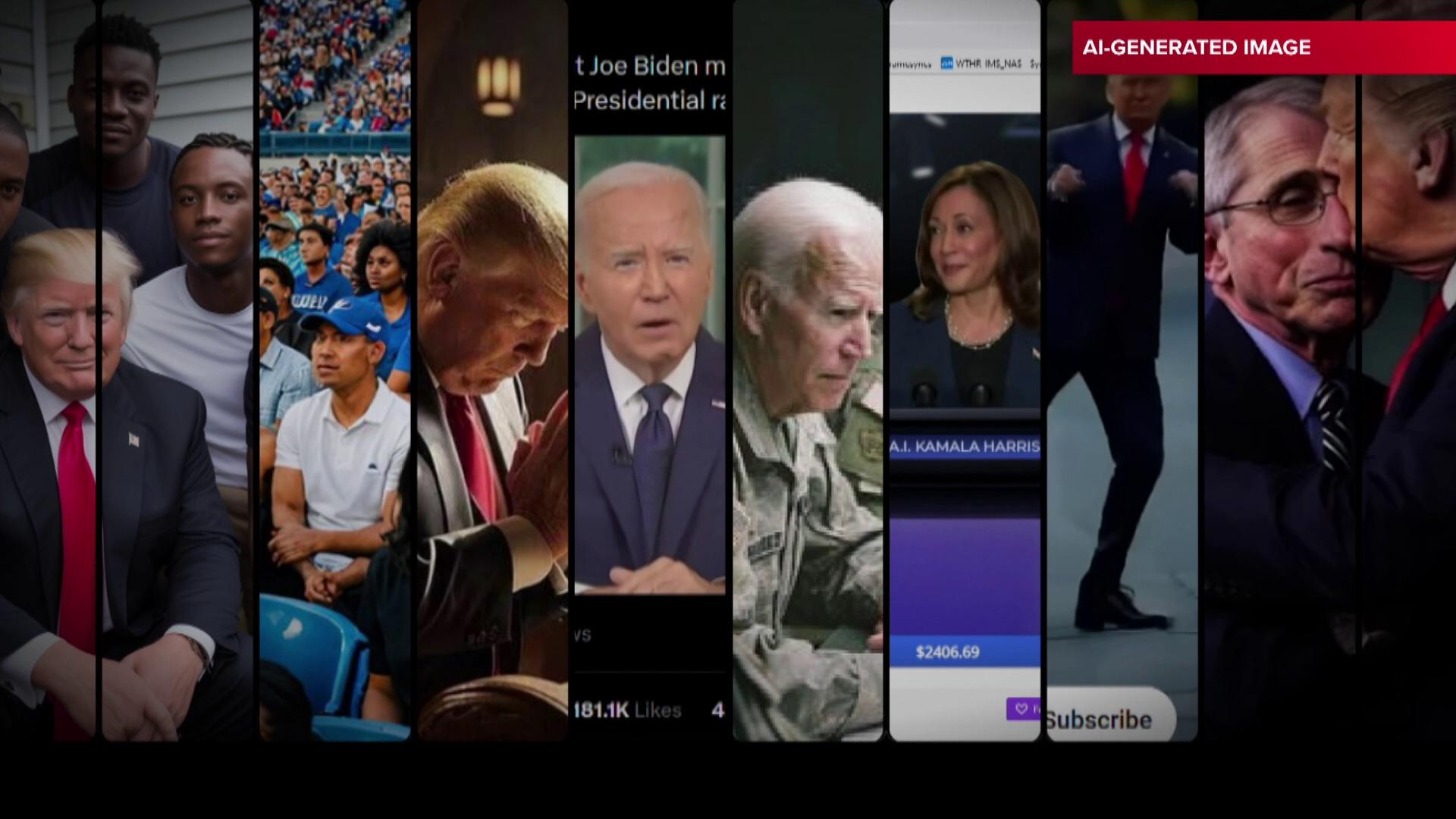

Fake videos, fake pictures and fake sound involving the candidates, their views and their activities are bombarding us online — sometimes without us even realizing it — trying to influence our vote.

Much of it is created by computer software featuring artificial intelligence, or "AI," that produces realistic-looking images and sound that intentionally blur the lines between what’s real and what’s not.

“2024 is the first artificial intelligence election, and as with any technology, there’s going to be good uses and evil uses,” said State Sen. Spencer Deery (R-District 23). “When I start thinking about where AI is going … then I get scared, and I think it should scare us.”

Based on the skyrocketing number of “deepfake” images created by AI, Deery is not alone is his concern about the impact of artificial intelligence on the upcoming election and its potential impact on politics and society.

13 Investigates has been digging into the world of political deepfakes to help you understand what they are, where they come from, how they’re made, and what’s being done to identify them and even regulate them. And while AI technology is rapidly advancing to make deepfakes easier to create and more difficult to detect, we also want you to know how to identify an AI-generated image to help you be a more informed voter on Election Day.

What is a deepfake?

A deepfake involves creating a fake image with the use of computer “deep learning” – thus the term deepfake.

Deep learning is a method in artificial intelligence that teaches computers to process data in a way that mimics the human brain.

Deepfakes can be used to replace faces, manipulate facial expressions, and synthesize speech.

Before exploring deepfakes in more detail, you should know not all of the political shenanigans we’re now experiencing are considered deepfakes. Manipulating images of politicians and world leaders is not new, with multiple examples of tampered and highly-edited photographs dating back to the 1800s.

Deceptive editing made headlines in the 2004 election, when two separate photos were edited together to falsely claim Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry spoke at an anti-war rally in 1972 with actress Jane Fonda. A doctored photograph of his opponent, George W. Bush, was edited to make it appear the Republican candidate was reading to a class of school children from a book he was holding upside down.

With the rise and widespread popularity of cell phone cameras, digital images and editing software such as Adobe Photoshop starting in the 1990s, millions of people gained access to inexpensive technology to easily edit photos of people and their surroundings.

Deceptive editing and portraying images out of context is now a common tool in political advertising, highlighted this week in a new campaign ad released by Sen. Mike Braun in his bid to become Indiana’s next governor. The ad includes a deceptively edited photograph of his opponent, Jennifer McCormick. The original photograph shows the Democratic candidate speaking at a campaign rally surrounded by supporters holding “Jennifer McCormick” signs. For the TV commercial, Braun’s campaign edited all of the signs to read “No gas stoves” in an effort to portray his challenger as too progressive.

But technically, those are not deepfakes, which can take deception to a whole new level. Using artificial intelligence, users can ask a computer to create entirely new images that never before existed based on situations that never happened.

Want to create a fabricated photo of Vice President Kamala Harris holding a gun, former President Donald Trump celebrating with Taliban soldiers or the two candidates hanging out on the beach together? AI can do that.

Want to see a fake photograph of President Joe Biden appearing to review a plan to steal votes in Pennsylvania? That deepfake already exists.

Taylor Swift’s 2024 endorsement of Trump and the widely-circulated photos on social media showing Swifties in Trump t-shirts — that never happened and nearly all of those images were AI-generated deepfakes.

Artificial intelligence is also being used to make deepfake videos, creating nearly identical voice clones of politicians saying things they did not say. Additional software can alter candidates’ lip movements. Marry together the altered audio and video and the possibilities for political deception are nearly endless.

Many of the deepfakes we see are meant for fun or political parody, such as candidates dancing in the street or engaging in ongoing presidential debates where users get to decide what they’re saying (often with risqué and nonsensical dialogue).

But we’ve already seen other deepfakes intended to influence voter perception, behavior and action.

A robocall sent to New Hampshire voters in January told them not to vote in the state primary. It sounded just like the president, but instead was a clone of Biden’s voice generated by computer. The man who is allegedly responsible for the fake call now faces criminal charges and millions of dollars in possible fines.

Other deepfakes targeted Trump, such as this ad linked to a political action committee supporting Florida governor and former Republican presidential candidate Ron DeSantis. The ad features an audio clone of Trump’s voice that makes it sound like he’s attacking the governor of Iowa before that state’s presidential primary.

Why experts are worried about deepfakes

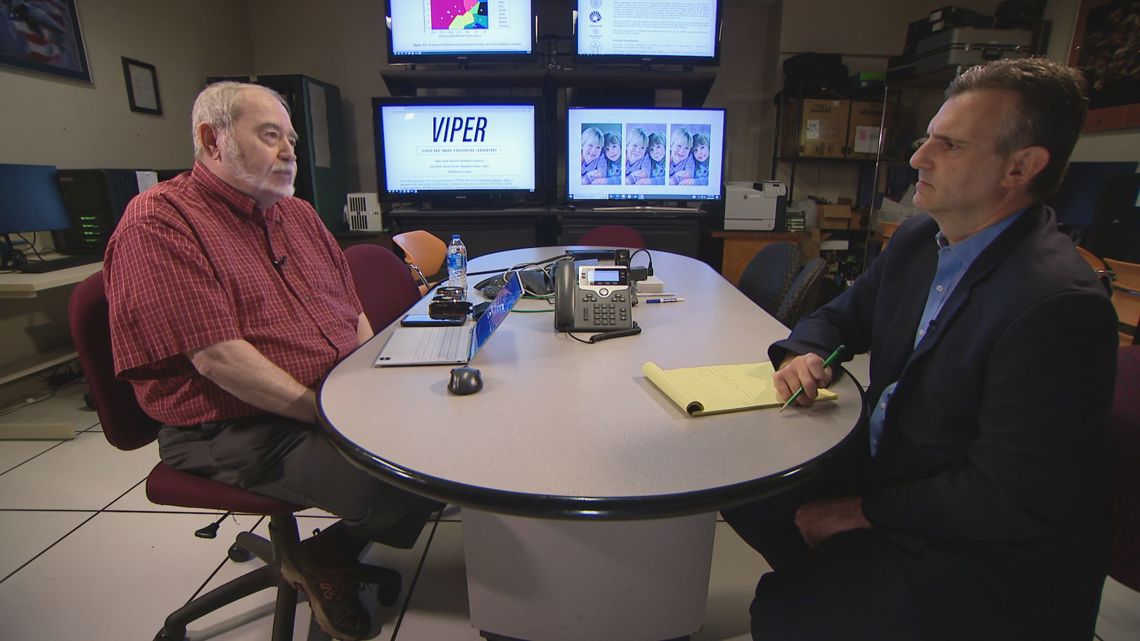

Purdue University is one of many colleges around the country where experts are now tracking deepfakes.

At Purdue’s Video and Image Processing Laboratory, professor Ed Delp and a team of graduate students use powerful computers to help detect which images are fake and which are real.

“I’m worried about what’s going to happen in the future,” Delp told 13News. “It’s going to get a lot worse before it gets better. The average person may be a position where they cannot believe anything that they see online or hear online, even read online, because it may all be synthetically generated. It’s going to cause real problems for our society.”

Delp’s biggest concern is that AI technology and software is advancing at a staggering pace. Research in his lab focuses on identifying images and video that have been created using that technology, but he fears the deep learning that now fuels computers’ ability to create AI is now outpacing researchers’ ability to keep up.

“It’s going to be an arms race between the people making those tools and the people like me who are developing tools that can detect whether the images have been synthetically manipulated or generated,” he said. “We’re seeing a lot more nefarious uses of this stuff … and these techniques can start a war.”

Deepfake images and videos have already circulated involving the wars in Ukraine and Israel, as well as how U.S. political leaders have responded to those conflicts.

Because the stakes are so high — both in politics and in world events — two other Purdue faculty are working to catalog deepfakes so they can be tracked and analyzed.

Daniel Schiff and Kaylyn Jackson Schiff, co-directors of Purdue’s Governance and Responsible AI Lab, recently launched the Political Deepfake Incident Database. Students have been busy adding hundreds of new online incidents in the past several weeks.

“A good portion of the images and videos we see are satirical, trying to poke fun at something, but the lines are getting kind of gray there,” explained Purdue assistant professor Kaylyn Jackson Schiff. “We’re seeing deepfake images that are originally shared for one purpose then be shared by others for another purpose.”

In other words, researchers see that political deepfakes that were created for parody and intended as a joke are later being shared online out of context where the joke is lost and the fake video can be viewed as real.

A fake campaign ad of Vice President Harris, originally posted and labeled as satire, was widely circulated on social media without any acknowledgment that all of its audio is an AI-generated clone. In some cases, the fake ad was later reposted with statements suggesting the statements by Harris are real even though they are not.

“Inflaming partisan polarization, inflaming our negative feelings towards one another, impacting social cohesion that way is definitely an area I’m concerned about with these deepfakes,” Jackson Schiff said.

Many people believe deepfake images and videos are real because they simply want to believe that.

“It’s called confirmation bias. If they have an idea of something they believe, then anything they see that confirms it, they’ll believe it whether it’s real or not,” Delp said.

That confirmation bias is one of the reasons deepfakes continue to flood social media platforms, which serve as a primary sources of news of information for millions of voters. And for those looking to trick vulnerable voters with fake videos and images, researchers say deepfakes are often effective.

“Generally, people have a 50-50 ability to distinguish real from fake content, so they will believe deepfakes very often,” said assistant professor Daniel Schiff.

Easy and cheap to make

To demonstrate how AI technology works — and how easy it is to use — graduate students at the Purdue Video and Image Processing Laboratory offered to make a deepfake video of 13News investigative reporter Bob Segall to include with this story.

The students first collected videos of Segall that they found online and downloaded that video into an online voice generator that can create voice clones in multiple languages.

Once the computerized voice generator had a large enough sample of online videos to replicate Segall’s voice tone and speech patterns, the students provided the voice generator with a script (written by 13News) to create an audio file that sounded as if the reporter had actually read it himself.

“We made you say things that you have not said by yourself before,” explained Kratika Bhagtani, a Ph.D. student in Purdue’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering who created the audio deepfake. “It’s fairly easy to do because all it needs is less than $10 to buy a few credits [to utilize the online voice generator service], and it takes less than a minute or a few seconds of audio to get the voice clone ready. This can be done by anybody.”

Once Bhagtani had created a clone of Segall’s voice, the next step was to make it appear as if Segall was saying those words himself.

For that part, Purdue graduate student Amit Yadav turned to another open-source AI service that is widely available online.

He used the service to manipulate a video of Segall in which the reporter was reading a script for a different news story on the set of the 13News studio. Yadav matched the cloned audio of Segall (discussing AI) to the previously recorded video (discussing something completely different). Then, with the help of AI, he changed the movement pattern of Segall’s lips, facial expressions and other body movements to make it appear as if Segall was actually speaking the cloned audio that had been produced by the audio generator.

“We can generate whatever speech we want and make you say anything we want. Simple as that,” Yadav said, showing the manipulated video he helped produce using AI.

13News used Purdue’s “Deepfake Bob Segall” in the broadcast version of this news story by recording a separate segment of Segall speaking in front of a studio green screen, then editing the real and deepfake versions of Segall together to make it appear they were interacting with one another.

Who’s behind the deepfakes?

Now that you have a sense about how deepfakes are created, let’s discuss who’s making them.

While the people and PACs (political action committees) that support specific candidates are responsible for some of the deepfakes that are spreading online and reaching our mobile phones, many political deepfakes originate overseas.

Last month, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence announced that Russia, Iran and China are using AI in sophisticated election interference efforts. According to NBC News, the National Security Agency has detected hackers and propagandists increasingly using AI to help them seem like convincing English speakers, with Russia boasting the biggest disinformation operation aimed at the U.S. election through AI-generated content including texts, images, audio and video.

Some of the foreign deepfakes are intended to increase support for Trump while others are more favorable to Harris, but all seem intent on impacting and interfering with the outcome of the election.

Other deepfake content creators have different goals, and some of those goals might surprise you.

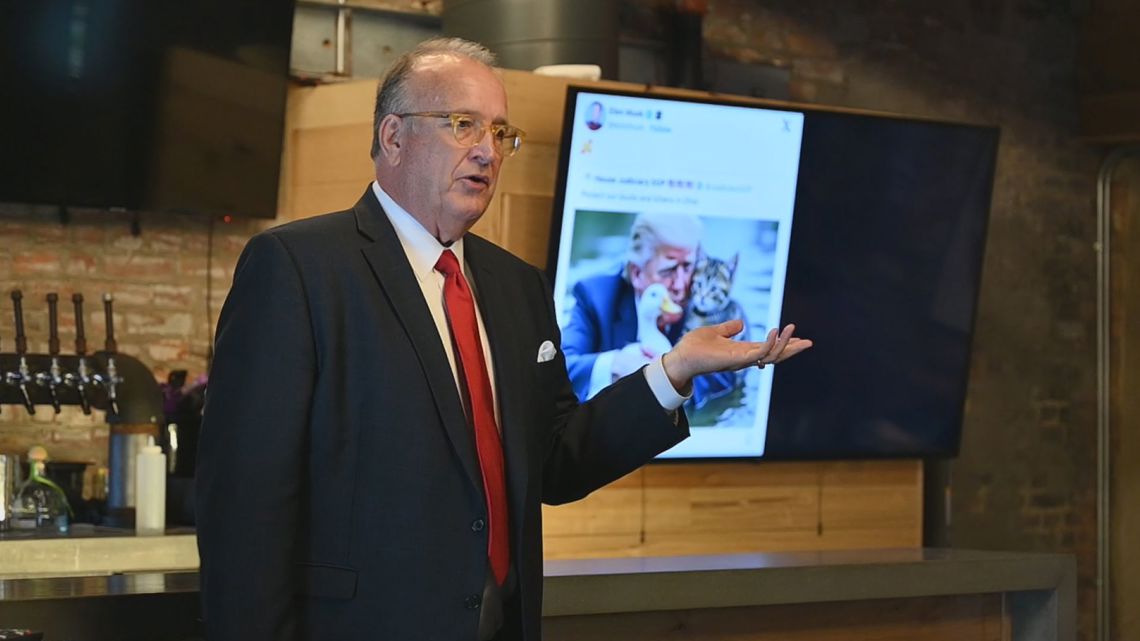

“In my case, it’s like generating fake news … but I’m trying to use the thing destroy the thing,” said Justin Brown, a video editor and political satirist in California.

Brown uses AI and his editing skills to poke fun at politics, and his videos have attracted millions of views online.

His political videos first made headlines in 2020 with a remix of then-President Trump’s interview with Axios reporter Jonathan Swan. Brown altered video to make it appear Trump was interviewing – and arguing with – himself.

Since then, he has used AI to alter videos of some of the world’s most powerful politicians and world leaders, resulting in sometimes lighthearted, sometimes poignant social commentary on social issues that he finds most important.

“Are you OK with … putting words into someone else’s mouth, making them say things they did not say?” Segall asked Brown.

“Yeah,” he responded. “I have no qualms putting words in their mouths to strip them of some of that power and give a little back to us.”

Working in an industry that has seen writers and editors face job cuts due to the emergence of artificial intelligence, Brown said his videos are intended not just to undermine politicians, but also to attack AI — the very technology he’s using to make the videos.

“I hate this thing,” Brown told 13News. “I’m always trying to get it in trouble. I’m always trying to stir up trouble with AI and get a lot of attention on the negative aspects of AI. I’m always trying to say some of the craziest things possible just to get the attention and get the interviews like this because I think it’s a bigger conversation we need to have that we’re not having on a big enough scale: that the negative impacts of AI are not around the corner, they’re already here and only going to get worse. So we should start figuring out how we want to deal with this new technology before it gets out of hand.”

Taking legal action

Many lawmakers also say it’s time to deal with AI.

This year alone, state lawmakers in Indiana introduced six separate bills to address deepfakes.

Two of those bills passed and have been signed into law, including HB 1133, that requires AI and fake content in political ads to be disclosed and SB 150 that creates a state AI taskforce. Deery, one of the legislature’s leading advocates for curbing fake content in political campaigns, was a sponsor of HB 1133.

“The first and most important thing is we want to protect the integrity of the election,” Deery told 13News. “But with all this fabricated media, I also fear that we get worse candidates, both because good ones don’t want to run or because good ones lose for reasons that are not based in reality. It’s time that we get ahead of this before it gets out of control.”

There are also efforts to enact a national law pertaining to deepfakes, although lawmakers have not yet agreed to terms on legislation.

Last year, Congress considered HR 5586, titled the DEEPFAKES Accountability Act. Designed “to protect national security against threats posed by deepfake technology and to provide legal recourse to victims of harmful deepfakes,” the bill would have established both criminal and civil penalties for those who violate the law.

This week, a judge blocked a new California law allowing any person to sue for damages over election deepfakes. While the federal judge said AI and deepfakes pose significant risks, he issued a preliminary injunction against the law because he said it likely violates the First Amendment.

When it comes to combatting the spread of misinformation from deepfakes and limiting their negative impact on elections and society, Delp said he believes legislation should not be the only strategy. He favors school districts offering more robust education for students in grades K-12 to teach the ethical use of AI tools and the internet, and he would like to see media companies take more steps to protect and verify their content to help the public spot what is fake.

“We can be doing more, and it has to start at an early age,” the Purdue professor said. “We all need to know what to look for and how to recognize content that’s been synthetically manipulated.”

How to spot a deepfake

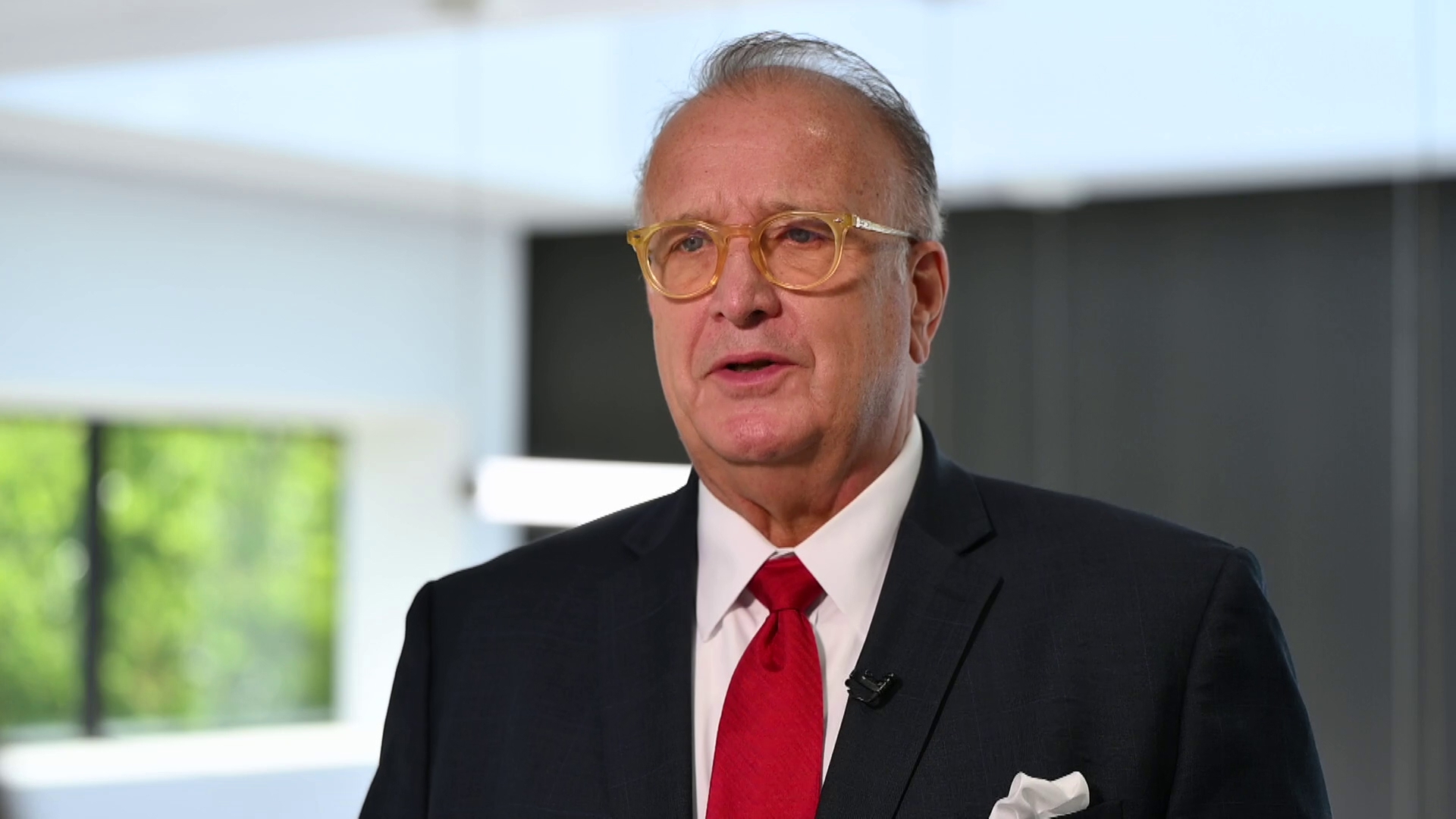

Educating ourselves about AI is important because deepfakes are causing us to question what we’re seeing with our own eyes, according to Syracuse University journalism professor Al Tompkins, who’s been studying deepfakes for years.

“To me, the greater threat is not the fake photos. It’s that you are not going to believe the real photos,” Tompkins said.

That is already happening in this election, with widely-circulated claims from Trump alleging that images of a Harris political rally in Michigan showed a massive crowd that was so large, it must have been an AI-generated deepfake. Multiple sources confirmed the images of the Harris rally were real and not deepfakes as the former president had claimed.

What can you do to separate out the real stuff from the fake? Tompkins advises you start by taking a deep breath.

“Most disinformation has one thing in common and that is it raises your emotion, because when your emotions go high your reasoning goes down. You stop thinking,” he said. “When you feel your blood pressure going up, stop. Don’t share. Don’t react. Don’t comment. Don’t do anything. Just stop and say, ‘Let me just take a moment to see if this is real.’”

After you relax, it’s time to start zooming in — paying attention to the fine details of the image or video to look for any telltale signs of AI, altering or manipulation.

Tompkins said such signs include an extra or missing finger, a strangely-shaped eye or ear, a misspelled word on a shirt or street sign, or a flag that is missing stripes or stars. When watching videos that appear to show someone saying something surprising or out of the ordinary, pay special attention to movement and shading around their mouth, lips, cheeks and teeth – the areas most likely to be impacted when attempting to sync up video with AI-generated audio. And listen for unusual inflections and speech patterns that differ from the speaker’s normal speaking.

It’s important to point out, AI technology is advancing so quickly, it’s not always possible to tell a deepfake from a real image.

“Where we are going in the period of a year or two, it’s going to be a quantum leap, and there’s no doubt you’re going to be able to create completely believable fakes that are going to be almost imperceptible to most people,” Tompkins said.

That’s why it’s important to also rely on other tools and resources to detect deepfake images.

One option is called a “reverse image search” to determine if an image is authentic. That type of search can be done quickly with Google Images by clicking on the camera that appears inside the Google search bar. You can then download the image to see if, when, and where that photo has appeared before, helping you identify the origin of the picture and whether the image has been manipulated or taken out of context.

Media outlets and fact checking websites frequently publish reports about fake images soon after they are detected, so if you have doubts about the authenticity of a video or picture you see online, try conducting a simple online search such as “Is a photo showing ____ fake?” You can also enter a quick subject search on one of your favorite fact checker sites. Some of our favorites include Verify, Snopes, Politifact and FactCheck.

If you have suspicions that a video or image is not real, Tompkins believes spreading the image creates a bigger problem.

“I think we have a citizen responsibility to pass along things that we know to be true and not pass along things you don’t know to be true,” he said.

Tompkins also suggests asking common sense questions before sharing a video or image that could be a deepfake.

“Ask the most basic questions, the questions your mother would ask if you came home with some wild story when you were a kid in school: 'Where did you hear that? Who’d you hear that from? Where did they hear it from?' Just ask those questions,” he told 13News.

Other questions he suggests exploring:

- Does it really make any sense that this person would be doing what they did or saying what they said?

- What is the source of the image/video and what is the source’s credibility and reliability?

- Does the source of the information profit or benefit from the image/video being shared?

Lastly, Tompkins warns against being a victim of your own confirmation bias, which makes you more likely to believe fake pictures and videos that support your pre-existing beliefs about the political candidates you support and dislike.

“Just be open to truth that you don’t currently believe and ask questions,” he said. “Artificial intelligence is going to change us some, but only in the ways we choose to allow it.”

“I think voters should be skeptical but not to the point where they give up and don’t go vote,” Delp said. “I think it’s an American tradition to be skeptical during a political contest, and I think that’s a very healthy thing and good thing for our democracy.”