INDIANAPOLIS (WTHR) — The videos are emotionally gripping.

Men and women once confined to prison for crimes they did not commit, released into the arms of loved ones.

Some have served decades in state prisons around the country.

The heartbreaking scenes make us all wonder how it could happen? And once the video fades, what becomes of exonerees like Kristine Bunch?

WTHR cameras were there when Kristine fought for her freedom.

At home with Bunch, two healthy Alaskan Huskies come bounding down the stairs. Piper and Paxon are frisky, excited to be able to roam the house again after being in a closed room while Bunch talked about the last seven years.

"Come on guys. I know, I know, I know," she said petting them as they jumped and wagged their tails with joy.

Bunch's words ring with assurance, and rightfully so, because she really does know what it's like to have no freedom.

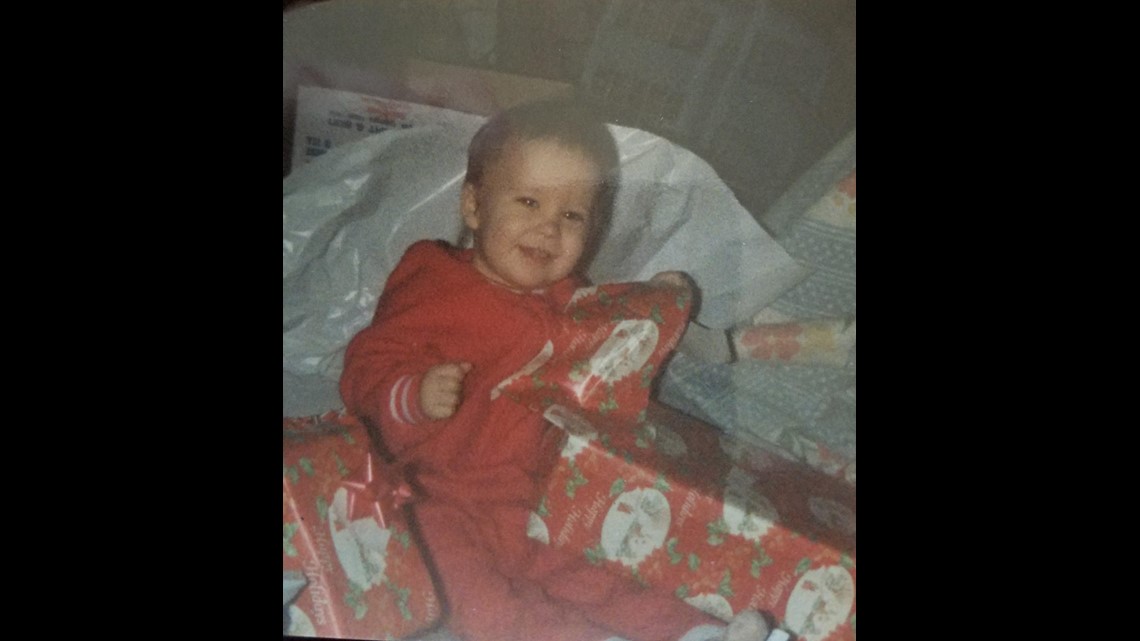

In 2012, 13 Investigates was there when Bunch walked out of a Decatur County courtroom and into the arms of her sobbing mother. She was finally free after serving 17 years at the Indiana Women's Prison. She had been convicted of arson and murder for a 1995 fire that killed her 3-year-old son Tony.

At the IWP she was known as inmate number 966069.

"I'll never forget it," she said.

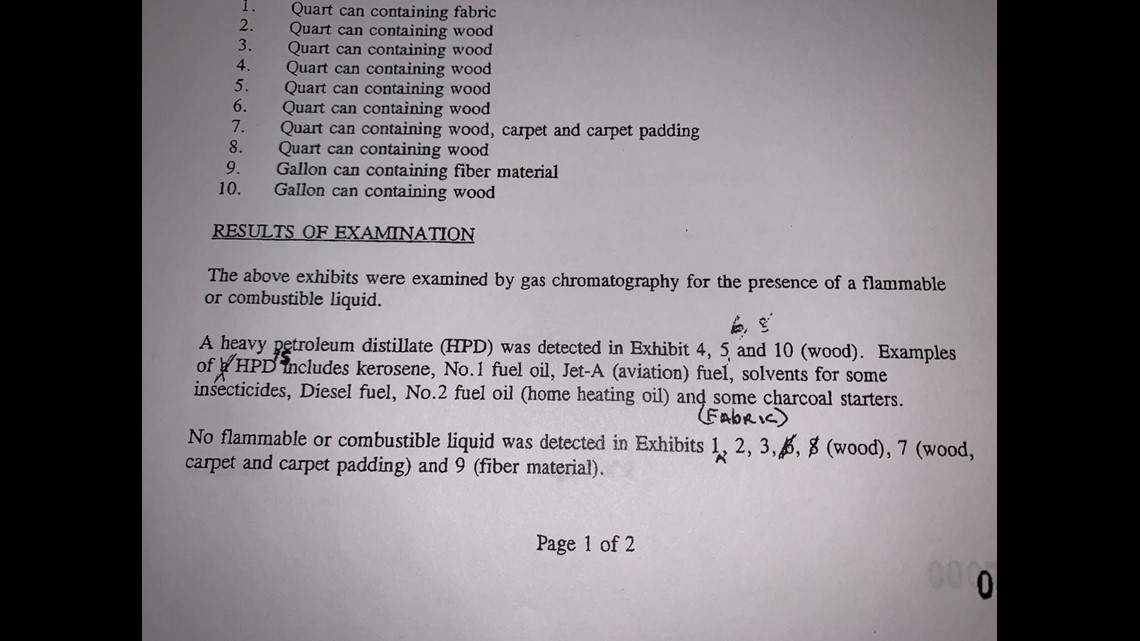

New evidence proved there was no crime. A fabricated report from the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) had been used to help convict Bunch. The report said accelerants were found in Tony's bedroom, when original reports showed there were no accelerants.

While the information helped Bunch prove her case and win her freedom, nothing prepared her for life outside prison walls. Just days after her release she found herself feeling lost and distraught.

"I just have to figure out if I can do this, (if I) can I make it? Can I live after everything that's happened?" she remembered thinking to herself.

A timeline of events leading to today's decision:

1996 - A Decatur County jury convicts Ms. Bunch of murdering 3-year-old son who died when their mobile home burned.

2006 - Ms. Bunch filed a petition seeking the post-conviction relief of a new trial, presenting evidence that showed, without question and on several different grounds, that her conviction was in error.

2010 - The trial court denied Ms. Bunch's request for a new trial, igonring overwhelming evidencee proving her innocence.

2011 - Ms. Bunch appealed the trial court's denial of post-conviction relief.

2011 - 13 Investigates does exclusive story on Bunch case.

2012 - The Indiana Court of Appeals overturned the lower court's ruling, granting Ms. Bunch a new trial.

For the first time Bunch is talking to 13 Investigates about the plight of exonerees across the state. She's one of 37 wrongfully convicted in Indiana and robbed of their lives and financial stability.

Freedom as a Hoosier means starting all over with nothing. No home, no work history, no money or even an I.D.

"I had to go get a prison I.D., so I could walk into the BMV to say 'OK, This is me. I need an I.D,'" she said.

But not even her trip to the BMV was simple.

"I was just sitting there crying because they're giving me a whole list of identification that I need. Thank goodness the manager walked over and sat down a newspaper and my picture was on the front page. He said, 'We know who she is. We need to help her with this,'" Bunch said.

At the county parole office where convicted offenders can sign up for multiple services, Bunch discovered something outrageously unfair: exonorees were not eligible because their convictions had been erased. And she's not the only one who has been left with few options.

"It's heartbreaking that we, we as a society broke these people," she said speaking as an advocate for those in similar situations. "We took everything from them and then we just throw them out and say 'Go, live, rebuild your life.'"

She moved to Illinois to rebuild her life near Northwestern's Center for Wrongful Conviction. That was the team that helped her to find new evidence in her case. She took a job working at the University's Department of Spiritual and Religious Life and helped spark criminal justice reform in Wyoming before deciding to head back to Indiana.

Since her return she started a not-for-profit to help exonerees called "Justis 4 Justus" or "J 4 J" for short.

"Yes, something horrible happened here and I lost 17 years of my life, but this is my home," she said.

Last year, Bunch spoke to Indiana lawmakers about the injustices facing exonerees.

The House pushed through new legislation to establish a new compensation fund that awards exonerees $50,000 for each year spent behind bars on a wrongful conviction. The legislation also provides some of the same services afforded to parolees.

"It's enough to get somebody a jump start," Bunch said.

In her case, the compensation could amount to about $850,000 if she's approved.

Under the guidelines, an exoneree is not eligible if they have previously received an award of damages related to the conviction or if they have a pending lawsuit.

Compensation is only paid to the individual or a guardian, and is paid in equal sums over a five-year period.

According to the Indiana Criminal Justice Institute, Bunch and at least six others are awaiting a state payout.

The money would allow Bunch to move out of her brother's home and into her own.

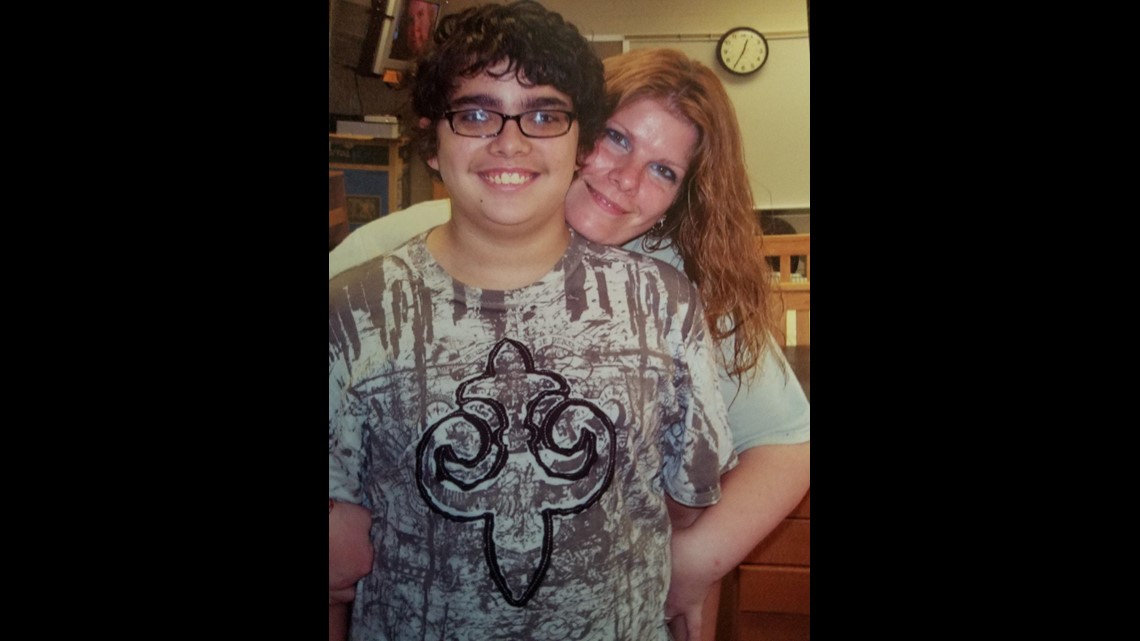

But the fund won't make up for the intangible losses she suffered, like missing her second son Trent grow up. She was six months pregnant when she was convicted and gave birth to Trent months later in prison.

He was 16 years old when she was released.

"We have a lot of exonerees coming out – their family is gone," she said.

Kristine had sought millions in a wrongful conviction lawsuit, but her case like many others was tossed out.

Government employees and experts have immunity unless someone can prove malicious intent. In her case, a federal court in the Southern District of Indiana ruled she had no standing despite the fabricated report.

"The man who changed that report, died before I was released," Bunch said.

And the two former Indiana State Fire Marshal Investigators who created the arson narrative never explained their actions either or admitted to the egregious mistake.

"Sometimes you get an apology," said 13 Investigates Reporter Sandra Chapman.

"Sometimes you don't," Bunch responded.

Bunch said she never got one. She admits her anger comes and goes.

"There is no amount of money you could ever give me to make up for that; to make it better, to fix it because it just can't be fixed," she said.

Instead, she's simply determined to live a meaningful life and to help those who have been harmed by injustice to start over too.

Bunch wants to see Indiana at the forefront of criminal justice reform and said there's more work to do.

The range of compensation rewards varies across the country.

States like Texas provide $80,000 a year to exonerees in addition to a retirement account, while Wisconsin only provides $5,000 a year for restitution. Some states provide no compensation. (To see data from the Innocence Project, click here and click "see state by state compensation laws.)

There is a small group of exonerees that win big payouts like Kevin Richardson.

Richardson is part of the "Exonerated Five" who were wrongfully convicted in the Central Park Assault case back in 1989.

13 Investigates also sat down and spoke with Richardson about the injustice he suffered as a 14-year-old and the reforms he still wants to see.