INDIANAPOLIS — A new state law that's supposed to compensate the wrongly convicted has yet to pay out any money and is not helping anyone.

13 Investigates looks into why exonerees are going without money and programs.

The process has left some victims of the state's egregious legal mistakes, feeling like they're facing a trial all over again.

Three Indiana exonerees were convicted of unthinkable crimes: a deadly arson, an armed robbery, and the murders of a wife and two children. After spending years in prison, Kristine Bunch, Keith Cooper and David Camm are all free to build new lives after the scourge of a wrongful conviction.

In July 2019, Indiana lawmakers decided it was time the State take some financial responsibility for what those wrongly convicted have suffered.

But 13 Investigates has discovered, the new state law passed last year to compensate those wrongfully convicted has not paid out one dime.

Under the law, those who have had convictions tossed or overturned are entitled to $50-thousand dollars for each year of incarceration, if they agree not to sue.

But there's another big catch. The Indiana Criminal Justice Institute gets to decide who's innocent and ultimately who's eligible.

Each case must face a stringent review.

"They're going to talk to everyone who opposed me to get their opinion to weigh in too. And then ultimately when the decision comes down it will be based on whether or not they believe I'm innocent," explained Bunch, who actually testified during the hearing process on the law.

Bunch who has worked in tandem with The Innocence Project in both Illinois and Idaho, said the compensation process could take up to 18-months in some programs. Indiana could be on track for an even longer wait, with time lost to the pandemic.

Bunch had hoped Indiana would have made some payouts by now. Even high profile cases like hers are uncertain.

"Does that feel like the spirit of what you thought this was going to be?" asked 13 Investigates Reporter, Sandra Chapman.

"It absolutely does not. It's very hard to feel like I'm going to be trying to prove my innocence for the rest of my life," she said.

According to the Criminal Justice Institute, a total of 15-Hoosiers have applied to the fund, since last November including Bunch.

In 1996 she was convicted and sentenced to 110-years for the arson and death of her 3-year old son.

But in 2012, 17-years after she was locked up, she won a new trial after Northwestern's Center for Wrongful Conviction discovered evidence provided by the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms had been altered. The Prosecutor in her case simply dropped the charges against her.

"I didn't have the luxury of going back to court and getting a 'not guilty'; an acquittal," she said. "I was released based on changes in fire science that proved there wasn't an arson in my home." she explained.

Law Professors like Fran Watson, understand the toll that time can take on those who have faced such extreme injustice.

"It's a continuation of something they've lived with for too long. This waiting for the lawyers, waiting for the courts," said Watson, who devotes time and expertise to the wrongful conviction team at the IU McKinney School of Law.

Watson is surprised as many as 15-Hoosiers have applied to Indiana's exoneration fund. In her experience, deciding who's entitled to the money is not always readily apparent.

"If I had that group of 15 before me, you know what I'd start with? If it were me I would look at the DNA cases where there were not other contributors," she told 13 Investigates. Those cases tend to be more "open and shut" if new DNA can show who the real perpetrator is and who it is not.

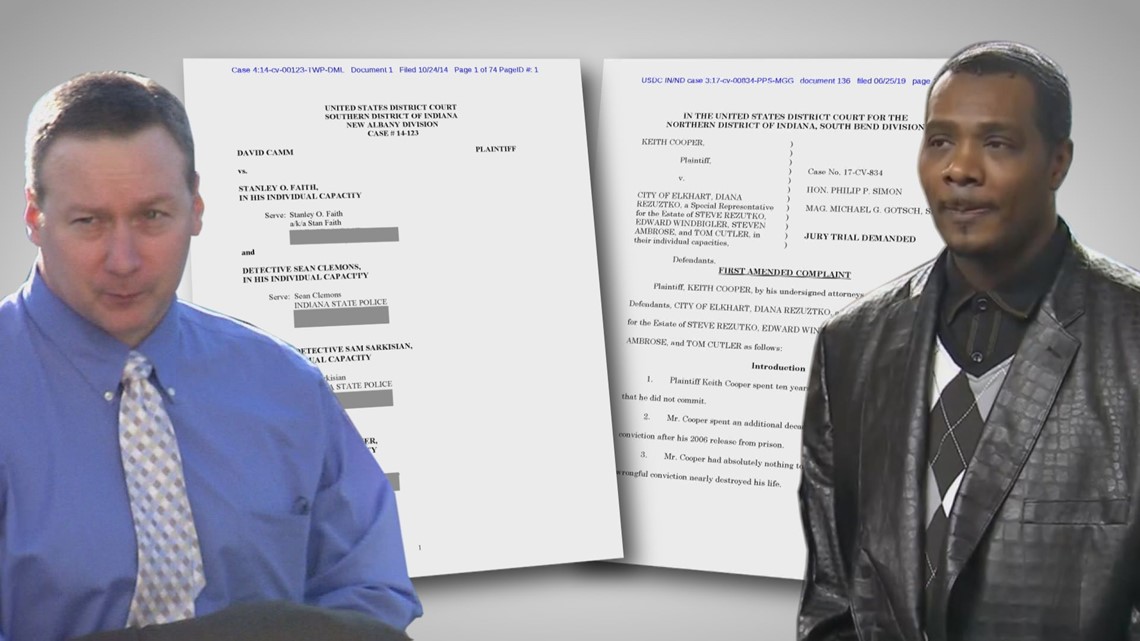

The cases for Keith Cooper and David Camm are good examples.

But those exonerees aren't waiting on the state. Instead of filing for money from Indiana’s exoneration fund, they're seeking bigger payouts with federal lawsuits.

Last year, the Indiana Court of Appeals cleared the way for Camm's hefty $30-Million dollar lawsuit to proceed.

The acquitted former Indiana State Trooper alleges DNA evidence was suppressed in his case and cost him 13 years behind bars for the September 2002 deaths of his wife and two children. Camm had been tried three different times before he was finally cleared. His life sentence was tossed out after DNA matched another man to the killings.

On February 9, 2017, after just a month on the job, Governor Eric Holcomb cleared Keith Cooper's name after DNA from a robbery case matched someone else.

"I issue this pardon this morning for the robbery conviction," said Holcomb in announcing his decision regarding the Elkhart County case.

"It feels like a thousand pounds of weight just lifted off my chest," said Cooper during an emotional interview a day later.

"I feel good. I'm glad I'm free," he said.

Cooper spent eight years of a 40-year sentence in prison. He was released in 2006 as part of a deal hatched by former Elkhart County Prosecutor Curtis Hill. Hill, who is now Indiana's outgoing Attorney General, agreed back then to allow Cooper to go free if Cooper withdrew his petition for exoneration.

Once released, Cooper spent the next eleven years seeking a pardon based on the new DNA evidence and witnesses who recanted their statements. Those same issues are at the center of Cooper's pending federal lawsuit against the Elkhart Police Department in which he's seeking potentially millions in damages.

Kristine Bunch had also initially filed a federal lawsuit but it was dismissed. The ATF agent who handled the altered evidence died while she was in prison. In addition, federal employees have government immunity.

Even though Bunch served more time than Camm and Cooper, she can only hope to collect $850-thousand dollars from the state of Indiana under the exoneration fund.

"This has taken an emotional toll and somewhere I just want to say that this is done and I can move forward," she told 13 Investigates.

"In the end their convictions were vacated or they would not be in this group of 15," said Professor Watson.

"They're not guilty. They're innocent," she said.

The Indiana Criminal Justice Institute says it's staff will carefully review each case.

"These claims are complex and the review process takes time. Each application must be reviewed for completeness, which not only requires a thorough examination of the documents provided by the claimants, but also, as part of the process, requires us to pursue other sources of information, such as court case records, and verify time served post-conviction. In order to do that, we have to submit requests to the external agencies where that information is housed. In addition, we have to make sure that all of the statutory criteria spelled out in the Indiana Code are met prior to making a decision to approve or deny a claim. Unfortunately, like every facet of life, COVID-19 has had an impact and slowed the process." said Ben Gavelek, Communications Director, Indiana Criminal Justice Institute.

Meanwhile State Representative Greg Steuerwald, (R) Avon one of the co-authors of the legislation told 13 Investigates he understands the concerns on all sides.

"This is a relatively new program, so there is a lot that goes into getting something like this up and running," said Steuerwald. "That being said, my understanding is that the agency is still in the process of reviewing applications and doing its due diligence. There are several criteria that need to be met in order to get approved, which requires a thoughtful and thorough examination. Ultimately, I would like to see some movement soon, but trust the agency is working and making headway as fast as it can," he said in a written statement.

There are also questions about a re-entry program tied to the fund and whether exonerees would be prohibited from taking advantage of some basic programs until they are ruled eligible by the Indiana Criminal Justice Institute.

After review, Gavelek told 13 Investigates there were issues with exonerees accessing traditional re-entry programs, but says the law addressed those inequities.

"The legislation...established two things. One, it provided clarification that an exoneree is eligible for transitional services," Gavelek said. "And, two, it ensured that applying for the Exoneration Fund, going through the process and/or receiving compensation, would have no impact on their eligibility to participate in those services."

"In other words, an exoneree has access and is eligible for those services now; they don't need to wait on CJI or apply to the Exoneration Fund." he explained.

IC 5-2-23-6 Eligibility for treatment programs

(b) Nothing in this chapter shall be construed to prevent a person from enrolling in, participating in, or receiving the benefit of one (1) or more of the following treatments, programs, or services if the person is otherwise eligible to receive or participate in the treatment, program, or service:

(1) Mental health evaluation or treatment.

(2) Substance abuse evaluation or treatment.

(3) Community transition programs or services.

(4) Any other program, service, or treatment that is designed to provide rehabilitation or reintegration services to an incarcerated person.