IMPD doesn't track unsolved homicides; number is 'roughly' at 1,000 cases

IMPD's case estimate spans 102 years. The department said it is making changes to improve record-keeping of unsolved homicides.

Hundreds of families wait years, even decades, for answers after a loved one is killed in Indianapolis and the case goes unsolved. 13 Investigates learned the number of these cases are overwhelming, not one, but two Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department units dedicated to solving homicides: the Homicide Unit and Unsolved Homicide Unit.

A month of emails and phone calls between 13 Investigates and the department resulted in IMPD estimating it has about 1,000 unsolved homicides. Some of those cases are part of IMPD’s former Cold Case Unit now called the Unsolved Homicide Unit.

A federal report stated the lack of data about these types of cases is a "crisis." One expert told 13 Investigates knowing how many unsolved homicides are out there allows police and community members to fully understand the scope of the problem so they can take steps to fix it.

“It has to be looked at as a crisis,” said Thomas McAndrew, with Innovative Forensic Investigations in Virginia. “Because often in the United States, until something is recognized as being a crisis, we don't get the adequate attention or funding for it.”

Running out of time

“I feel like maybe I'm running out of time,” Sharon Grubbs said.

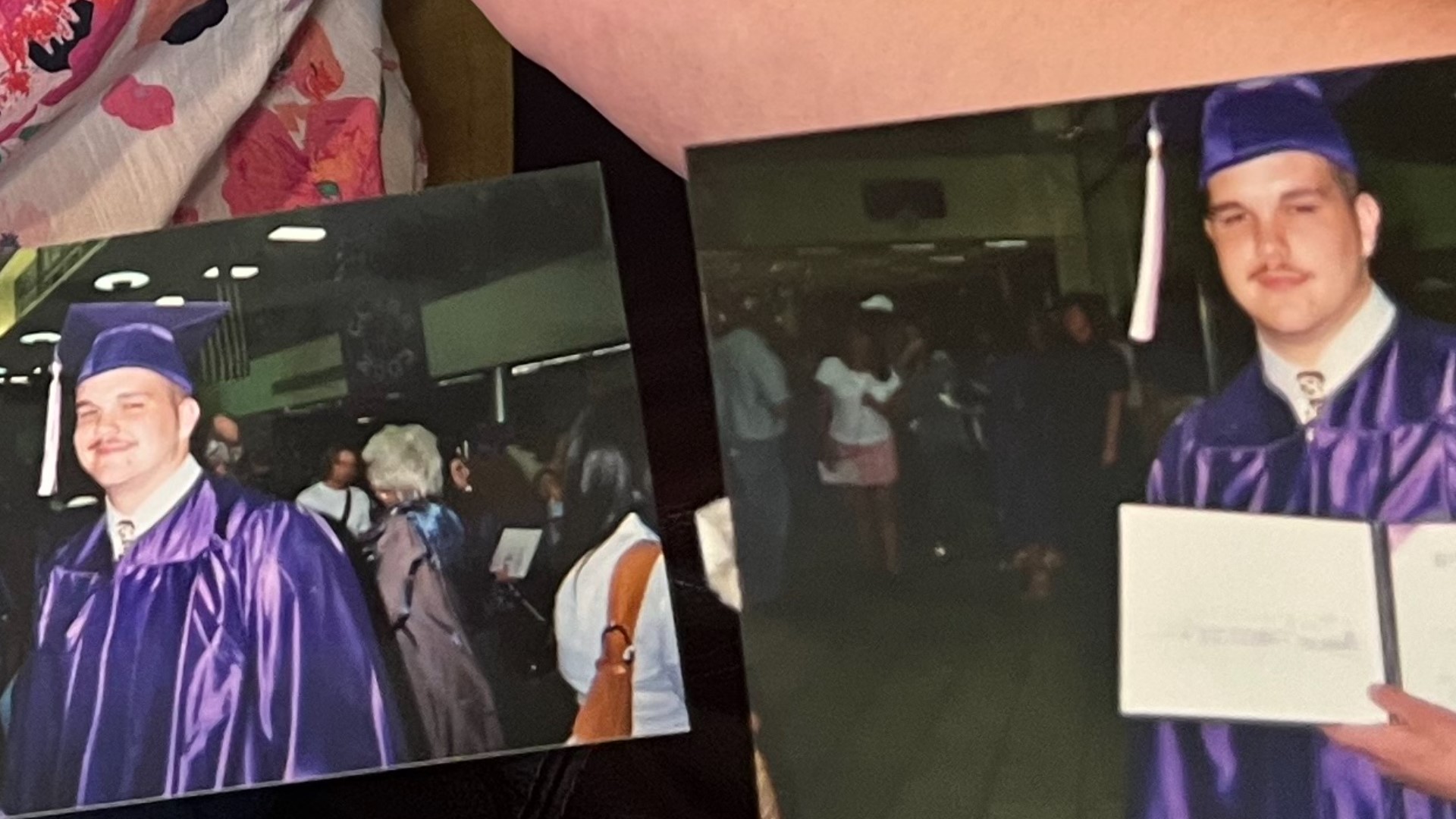

For 18 years, Grubbs has been waiting for answers about who killed her son, William “Stryker” Sircy, and why he was murdered. Detectives with the Marion County Sheriff’s Office first started investigating his case in 2005 when Sircy died at a west side apartment complex. Police told Grubbs Stryker was shot five times.

The case is now in the hands of IMPD’s Unsolved Homicide Unit — after a reorganization of the sheriff and police departments in 2007.

Grubbs said she has a good relationship with the latest detective handling her son’s case.

“I'm doing this because, if it gets to the cold case unit, I still have faith. I still have faith," Grubbs said. "I still have hope that someone will come forth and someone will help our family.”

Grubbs reached out to 13 Investigates after seeing our reporting in June about gun violence and the number of recent shootings that remain unsolved. 13 Investigates focused on the number of unsolved cases overwhelming the city’s homicide unit. Grubbs believes the same holds true for IMPD’s Unsolved Homicide Unit, which she saw firsthand during a visit to talk to the detective overseeing the case.

"The office is full of boxes, absolutely full,” Grubbs said. “And (the detective) had told me that there was another office that had just as many boxes, if not more. And that was horrifying to me that there were so many unsolved cases. So many people that haven't got answers for their loved ones.”

How many unsolved homicides?

13 Investigates asked IMPD for additional details about the Unsolved Homicide Unit. In June, a spokesperson reported there are five detectives assigned to the team. We also asked for the total number of cases the unit oversees. IMPD Lt. Shane Foley, who works in the Public Affairs Office, wrote:

“We don’t track this number and some of the historical data is not available. Every unsolved homicide from IPD, MCSD, and IMPD that is not currently assigned to a detective is under this unit’s purview. If a current homicide detective is still in the homicide unit, the case would still be assigned to him/her.”

After several additional emails and phone conversations, IMPD revised its response and told 13News the department has “roughly” 1,000 unsolved homicide cases dating back to 1920. The agency said it estimated that number by reviewing clearance rates but it continues to go through historical records to get a “more accurate count” of cases.

13 Investigates asked the department’s homicide branch commander why the department could not give a precise number of unsolved homicides.

“There's no centralized record for, ‘Hey, this is how many unsolved homicides we have’ versus all homicides," Capt. Rodger Spurgeon said.

Spurgeon said he also did not know how many of those cases were handled by the Unsolved Homicide Unit and how many remain in the Homicide Unit that picks up new cases.

Cold case crisis

13 Investigates turned to McAndrew to get his thoughts on IMPD’s inability to provide a clear number of unsolved homicides.

"I'm not at all surprised by that, because that is what we find throughout the entire United States," he said.

McAndrew is a retired Pennsylvania State Police investigator and was a member of the National Institute of Justice’s Cold Case Investigation Working Group. He was part of an effort in 2019 to release the National Best Practices for Implementing and Sustaining a Cold Case Investigation.

The report called the lack of data surrounding cold cases and unsolved homicides a “crisis.” McAndrew said that’s still the case.

“It's really only getting worse,” McAndrew said.

Worse because in Indianapolis and nationwide, the number of homicides is trending up over the last few decades, while police are generally solving a smaller percentage of those crimes.

For example, IMPD reported 226 homicides in 2022. In January 2023, the department released data showing 35% of those killings were cleared — meaning police have made an arrest or closed the investigation. The clearance rate increased to 41% by July 25 — meaning 133 killings remain unsolved. Back in 2018, IMPD reported in its annual report it had less than 200 homicides, and the clearance rate was 65%.

Grubbs told 13 Investigates she supports the police and believes they are working on her son’s case, based on recent updates from the detective. However, she’s worried so many cases remain unsolved.

“I just think that people are getting away with it and think they can do it again,” Grubbs said.

Each homicide that goes unsolved means a killer is potentially still at large. McAndrew said by not knowing the total number of unsolved homicides, police departments are not able to identify how large of a problem they’re dealing with. He said those numbers can help departments request more resources.

“The reason I like the number is simply to define the scope of the problem that you can go to your mayor, your commissioner, or your whoever's behind the purse strings” McAndrew said. “And you can say, ‘Listen, we have this many cases. We only have this many officers. What do you want to do about it?’”

“It comes down to indifference,” McAndrew said. “There’s not enough people involved or paying attention to the crisis.”

IMPD implementing changes

13 Investigates also reached out to other large policing agencies in the state and similarly-sized agencies nationwide. Not every department has a unit to focus specifically on cold cases or unsolved homicides. For some, one isn’t necessary. Other departments do not have the resources.

Indiana State Police posts some cold cases investigations online, but it dissolved its dedicated unit in 2010.

Overall, McAndrew thinks IMPD is moving in the right direction, even if it has room to improve.

“The most positive, telling thing to me, is that they’re actually trying something,” McAndrew said. “They may not have every answer in this. They may not be doing everything the same way we might have done it in Pennsylvania or whatever. But the fact that you have somebody in that department, in a high enough rank, to care about this issue, and try to get things done, is very, very significant.”

In past annual reports, IMPD listed statistics for the Cold Case Section, including the number of calls requiring follow-up, cases reviewed for evidence testing, murder arrests, cases prepared for trial and murder trials pending. IMPD’s 2021 annual report did not include information for the new Unsolved Homicide Unit, but in 2020, the former Cold Case Unit reviewed 92 cases for evidence testing, making one murder arrest and preparing two cases for trial.

Spurgeon said right now, the unit is going through an evolution and making changes. For several months a detective has been reorganizing old records and creating a new filing system. “Conduct an inventory of the number of unresolved cases” is the second recommendation listed in that federal best practices report. IMPD tells 13 Investigates it currently has three rooms filled with physical files but denied 13News’ request to visit those rooms.

The unit is also moving away from storing files in cardboard boxes and instead putting them into plastic containers to better preserve the records.

“While that still sounds very old school, it's a lot better than the boxes that we had," Spurgeon said, confirming files are now being saved electronically when they come in.

The department is reviewing how it decides when to move a case from the Homicide Unit to the Unsolved Homicide Unit. The current practice is to generally keep a case with the original lead detective and move the file to the unsolved unit only when that detective retires or is no longer in a policing role.

IMPD is discussing a guideline to transfer a case to the Unsolved Homicide Unit when it’s considered unsolved for a specific number of years.

There is not a universal definition of what an unsolved or cold case is. Each agency can decide for itself. According to IMPD, a homicide case is unsolved when all workable leads dry up. The 2019 federal best practices report defines a cold case as one that “has remained unsolved for at least three years and has the potential to be solved through newly acquired information or advanced technologies to analyze evidence.”

Another change involves staffing. In the past, IMPD primarily assigned detectives to the unit at the end of their careers. Now, the department is looking to staff the unit with more mid-career detectives to improve stability.

The department is also working to create a solvability matrix — a system to identify the cases detectives should work on first. These would be cases with the most likely chance of being solved. Resources are limited. IMPD has five detectives currently in the unit, with at least one close to retiring.

“I think It's unfortunate that we have more unsolved cases than we can reasonably put resources to proactively go after every single case on a regular basis,” Spurgeon said. “Yes, that's an unfortunate fact. As far as a crisis, I mean, you know, I'll leave that to others to label.”

The NIJ’s report also suggests departments post cold cases online so the public knows what cases are still being worked. Another recommendation is to secure the help of volunteers, possibly utilizing the skills of retired officers or people in academia.

“What do you have to lose?” McAndrew said. “Listen, if a case is cold, it's been sitting for 30, 35, 40 years with nothing on it, you will risk nothing by using vetted volunteers.”

Hope for families

The report says the 23 recommendations may not be right for every department, but they are best practices identified through research and results.

Ultimately, law enforcement experts tell 13News most cold cases are solved by one of two things: new technology or a witness willing to come forward.

Grubbs is hoping for the latter. She wanted to share Sircy’s story in hopes of encouraging someone with information to come forward. She hopes the people who know what happened have matured and are willing to talk.

“If they don't come forth for my case, maybe they'll hear me and they'll come forth for somebody else's case,” Grubbs said.

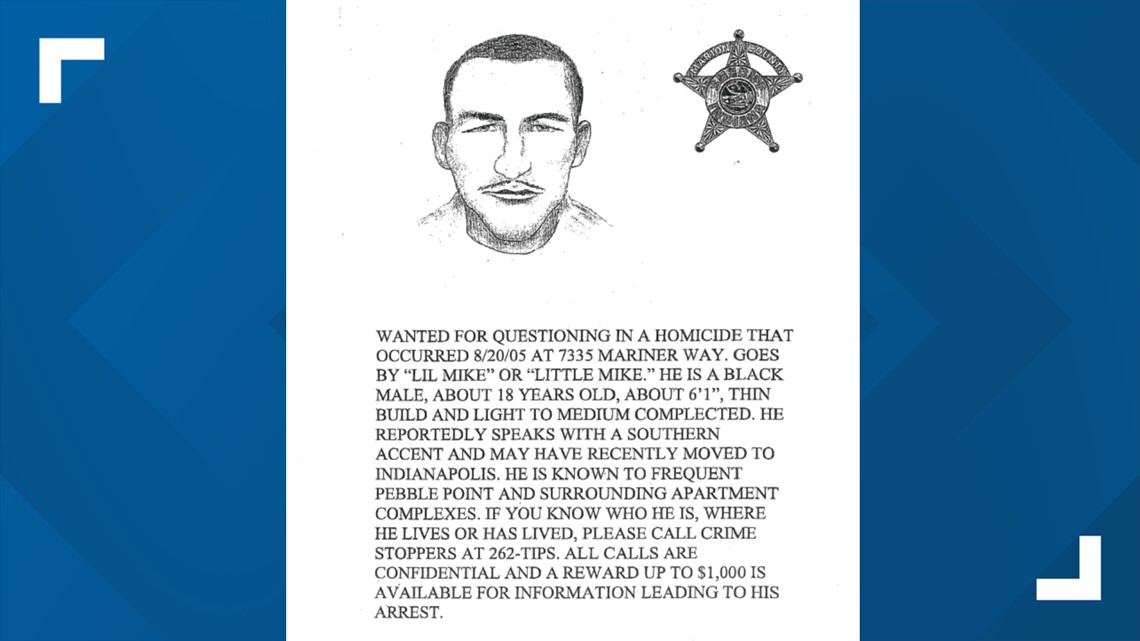

Grubbs shared a sketch of a person she says detectives wanted to talk to back in 2005 about Stryker’s killing on Mariner Way. They sent out a bulletin hoping to speak to the man who went by “Lil Mike” or “Little Mike.” Nearly two decades ago, the flyer noted the man was known to frequent the Pebble Point Apartments and nearby apartment complexes.

“They're fairly certain they know who it did,” Grubbs said. “We just need someone to come forth and give (police) some information so we can actually close this case."

That way, detectives can then move on to solving the next unsolved homicide.

“I feel incredibly sad for the people that are starting this process,” Grubbs said.