INDIANAPOLIS (WTHR) — As you pull into the driveway, the Boling home looks like any other vinyl-sided, brick-trimmed subdivision house on the south side of Indianapolis. On the inside, however, it is unlike any other home in their south side neighborhood.

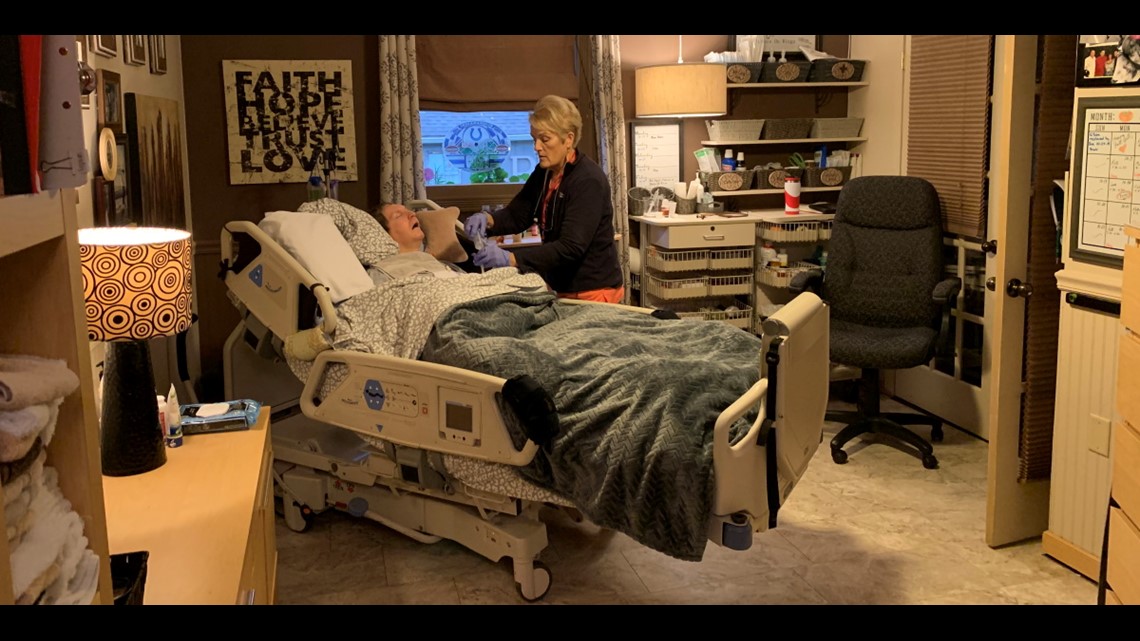

The pantry has no jars of peanut butter or boxes of macaroni and cheese. Instead, it is stocked with syringes, feeding tube bags and countless bottles of prescription medication. The living room has been converted into a cozy medical suite with a respirator, oxygen tank, suction machine and other devices more typically seen in a hospital room.

The sounds of children playing and medical apparatus beeping are woven together into a chaotic yet sweet symphony that fills every corner of the house.

"Yeah, it's kinda different. I always tell people we have a mini ICU at our house," said Natasha Boling, chuckling as she gave a tour.

Natasha and her husband, Shane, have four kids – all adopted and all with special medical needs.

Sammy and Xavier are both 3. Sammy has arthrogryposis, a rare disorder that causes joint stiffness and muscle weakness throughout his body. Xavier has cystic fibrosis, an incurable genetic disease resulting in persistent lung infections and restricted breathing. It also impacts his digestion. Doctors had to remove half of Xavier's small intestine at birth.

Rayva is the big sister. The 11-year-old was diagnosed with cerebral palsy and epilepsy, which cause seizures and severely impact her movement and posture. Rayva is also deaf and blind.

And then there's Elias. Cardiac arrest when he was a baby left Elias with severe brain damage. Every breath he takes is thanks to a respirator. Doctors expected Elias not to live to see his second birthday. He is now 6-and-a-half.

Most of the Boling kids rely on liquid nutrition taken through feeding tubes in their stomachs. The daily routine of feedings, breathing treatments, medications and monitoring – not to mention getting the children dressed and bathed, playing with them and getting them to their medical appointments – is long and exhausting. Natasha and Shane wouldn't have it any other way. It is the life they have chosen.

"Other people say 'I don't know how you do it,' and you do it because they need it. So you figure it out," Natasha told WTHR.

"You have your ups and downs, but it's all worth it. You're giving them a better life," added Shane.

Despite all the children's medical challenges, doctors say there's no reason the Boling kids cannot live at home, and that is where Natasha and Shane want them to be. But for these children and many other medically-fragile Hoosiers, home healthcare is difficult – sometimes impossible – due to a chronic shortage of home nurses.

A WTHR investigation finds Indiana's home nursing shortage impacts thousands of the state's most vulnerable residents, often with dire consequences. Much-needed funding to address the shortage was rejected or diverted. And while state leaders have known about the problem for years – and have been ordered to fix it – 13 Investigates discovered families across Indiana continue to struggle daily to access the home healthcare they desperately need.

Why mom sleeps on the floor

There is plenty of research showing chronically-ill patients fare as well or better at home as in long-term care facilities – often at a lower cost. And given a choice, the vast majority of patients say they prefer to receive long-term care in a home setting rather than in a nursing home.

That is the choice the Bolings made. They understand providing their children around-the-clock medical care 365 days a year comes with challenges. Especially for Elias, having someone nearby at every moment is literally a matter of life and death.

"His machine breathes for him. If he moves his arms and knocks it off or if his trach [breathing tube] comes out, he will die within two minutes," Natasha explained.

To meet the family's complex medical needs, the Bolings rely on home nurses. The licensed, skilled-care nurses allow Natasha to work a day job as a special education teacher and Shane to work nights at a local trucking company to pay their bills. But the family does not get most of the nursing care it is entitled to receive.

Elias is supposed to have an overnight nurse seven nights a week so Natasha can sleep while Shane is at work. The state Medicaid program has pre-authorized that nighttime nursing care and has agreed to pay for it. But a home nurse comes just two nights each week – not seven. On the other five nights, Natasha sleeps on the floor next to Elias' bed. She sets the alarm on her cellphone to go off every few hours to check Elias' vital signs and to give her son his required medical treatments.

Daytime nurses are scheduled on weekdays to help care for the Boling children while Natasha works and Shane gets sleep. But there is considerable turnover, causing lapses in care that force Natasha to stay home from her job. Because Natasha missed so many days of work last year due to a lack of home nursing care, she lost her eligibility under the Family Medical Leave Act – giving her less flexibility to take off extra time to care for her children when home nurses leave for jobs elsewhere.

Of the 207 hours of pre-authorized nursing care approved weekly by the state Medicaid program, the Bolings receive only 103 hours of actual nursing – half of the care they should be receiving.

"We've tried to get more hours but there's no nurses available," said Natasha. "And if a nurse gets sick, goes on vacation or her car breaks down and she can't come, that's pretty much it. We don't have nursing."

In addition to the regular day and night hours approved by Indiana's pre-authorized Medicaid Home Health program, the Bolings also qualify for additional home nursing care through a separate Medicaid waiver program. Also known as respite care offered through the state's Home and Community Based Services program, the waivers pay for nurses on weekends and evenings to care for the children while Natasha and Shane go to the grocery store, pharmacy or just have a little down time.

Between all their special-needs children, the Bolings are authorized to receive 180 hours of respite home nursing each month. But they get none. Zero. There simply are no licensed home healthcare nurses available to work those hours.

"We haven't had weekends covered in years. It's just us," said Shane.

So each month, the Bolings miss out on hundreds of hours of home nursing care they are supposed to be getting for their children. And yet the Bolings say they are fortunate; they get at least some home nursing.

"Yeah, we're lucky," said Natasha. "There's a lot of families that don't have it at all."

8 months. 0 nurses.

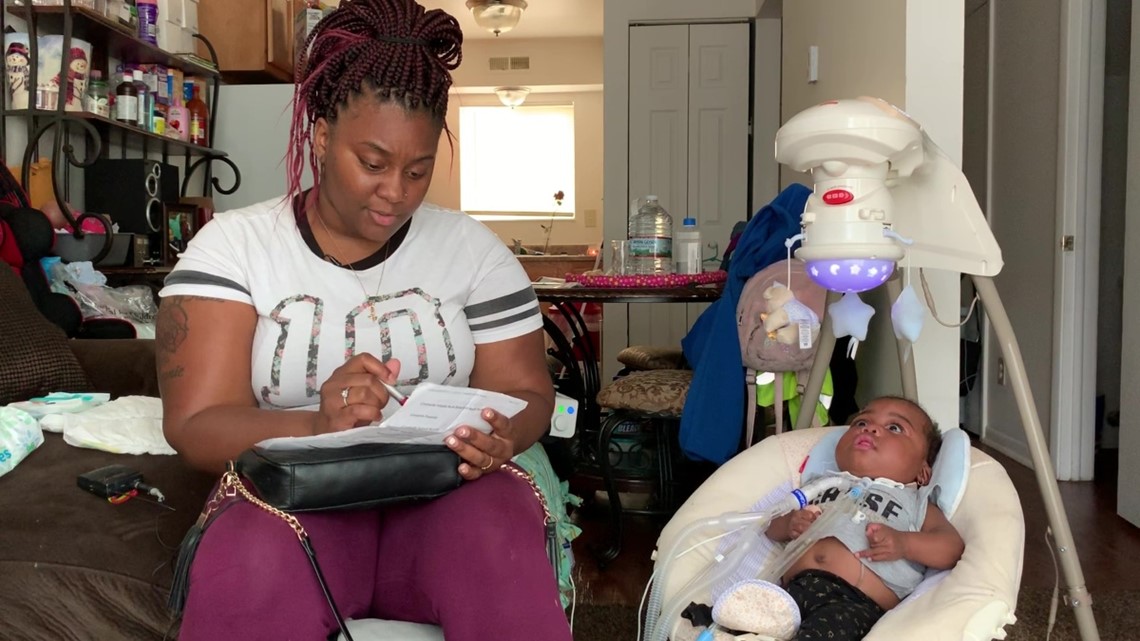

Tyesha Wright has one of those families. She is desperately seeking a home nurse to help care for her 1-year-old daughter Desire.

Because Desire was born almost four months early, her lungs needed a lot of help. Doctors inserted a tube down her throat so she could breathe with a ventilator while she grew stronger. When she was six months old, they removed the intubation tube and performed a tracheotomy (an incision in her neck to open a direct airway to the trachea) to improve her odds of a long-term recovery.

Three months later, showing she could finally breathe without constant use of a respirator, Desire was ready to go home. Doctors released the infant from the hospital because the state Medicaid program approved Desire for 18 hours of home nursing care every day.

"The moment we left the hospital, we were supposed to have a nurse," Wright told 13 Investigates. "Actually, they said two. They told us they'd have two trained caregivers to be at home with us before she could leave."

But she never got a call or a knock on the door. After waiting a few weeks for a home nurse that never came, Wright began calling home healthcare agencies herself. They all told her the same thing.

This summer, five months after Desire was released from the hospital, a home healthcare nursing agency suggested Wright move from Lafayette to Indianapolis, where a larger metropolitan area would surely offer more options to get the home nursing care she was promised.

So the single mother moved Desire and her three other children to an apartment on the west side of Indianapolis and immediately began calling local home healthcare agencies and social service agencies to find a home nurse for her toddler. Still no luck.

Every week, Wright calls dozens of agencies that cover a 1,500-square-mile service area in central Indiana. She repeats her name. She again tells them about Desire. She explains over and over about her daughter's medical condition. About the pre-approvals she's received from Indiana Medicaid for 18 hours of daily nursing care. About what the hospital told her before Desire was released. About the call she had with the very same person the week before and the week before that.

None of it seems to be helping. All the agencies say they have no skilled nurses available to come to Wright's home. Eight months after Desire was released from the hospital – still relying on a tracheotomy tube and a ventilator to breathe – she has not received a single hour of home nursing.

It means Wright is solely responsible for the constant medical care Desire needs every day. And make no mistake, it's a full-time job, which means she cannot accept the full-time position she's been offered as a housekeeper at a downtown hotel.

"If we can't work, how are we supposed to survive? Not only can I not work, I cannot support my other kids, my household, my bills," Wright said, holding back tears. "It's unfair because the only option that they give us …"

The long pause that comes next is gut wrenching. As Wright's mind thinks ahead to the words she's about to say, tears roll down both of her cheek.

"… is to basically give our kids up to a facility. And it's not that we don't want them, it's that we need help!"

Heartbreaking reality

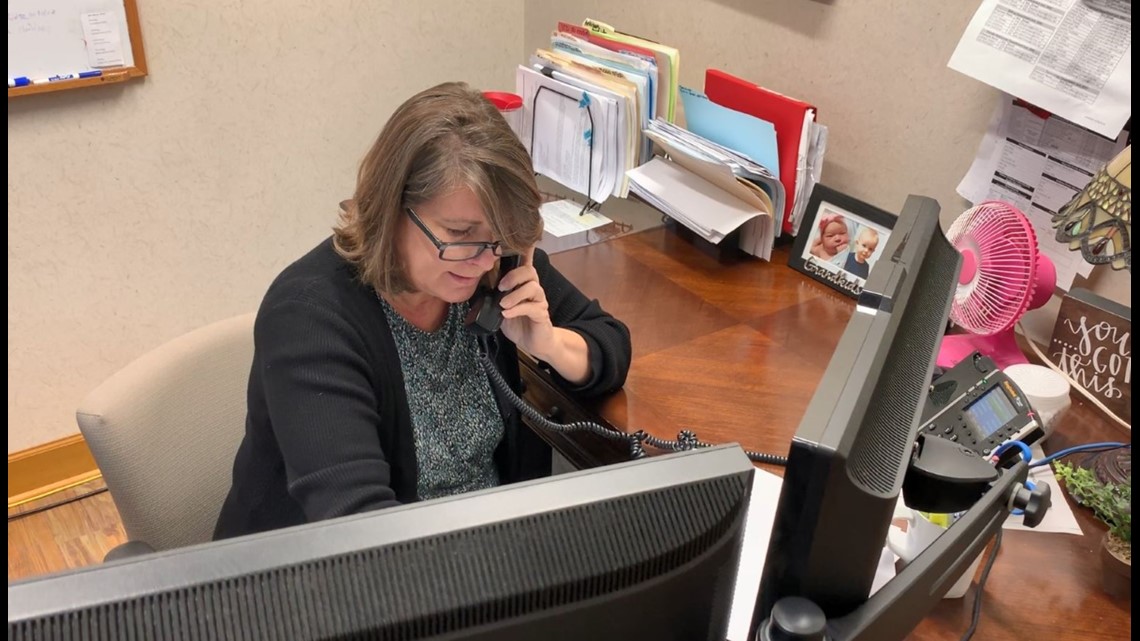

On the other end of the line during some of Tyesha Wright's phone calls is Maria Hunt.

She has spoken to Wright multiple times over the past eight weeks – each time the desperate mom calls Tendercare Home Health Services to see if a new nurse might be available.

"As of right now, there hasn't been any changes," Hunt told Wright during a recent phone call. "I know our medical director is working on it, so I'll be back in touch."

After the call, Hunt looked down at her desk and shook her head.

"These parents call back and you feel bad if you don't have any relief for them," she said. "It's been their third or fourth attempt and nobody's able to staff. It's really hard."

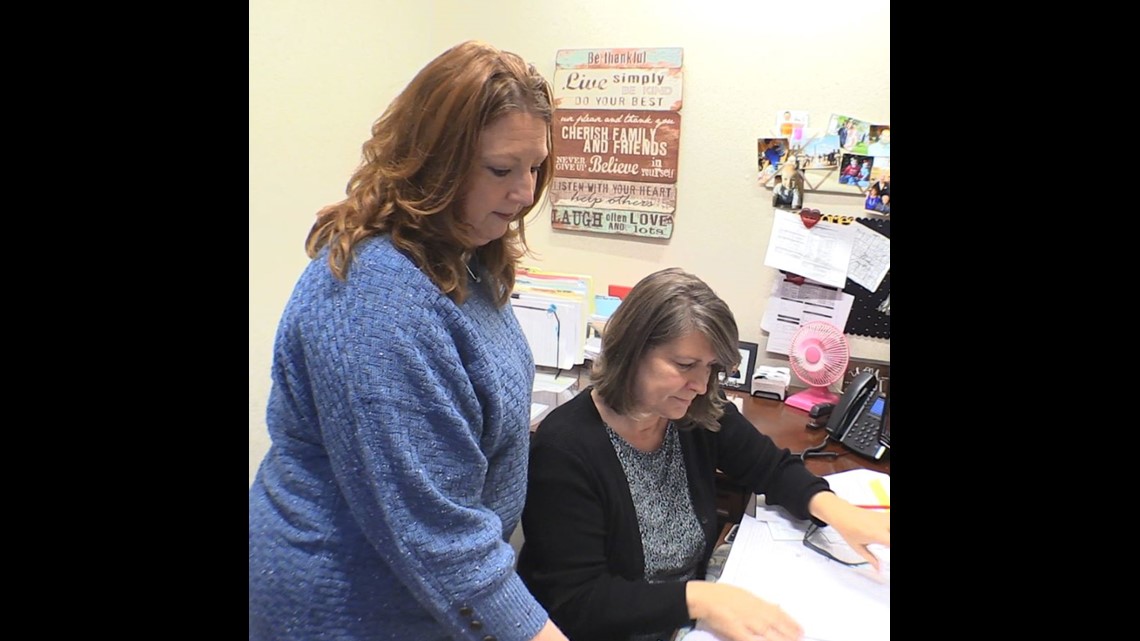

Discussing the shortage of home healthcare nurses facing agencies and families across Indiana, some Tendercare staff have trouble holding back their own tears.

"It's heartbreaking when you see these families are in crisis and you can't help them. It's terrible," said an emotional Leslie Deitchman, the agency's owner. She and her employees must turn away families now looking for in-home nursing.

"Since January we have declined 200 families," Deitchman told WTHR. "They get approved for these hours through Medicaid. When you get that news you're approved and you're going to get care ... it's kind of like getting a lottery ticket you can't cash because there's no one to take you. It really is heartbreaking."

Other home nursing agencies contacted by 13 Investigates share the same story: many Indiana families looking for skilled nursing care and not enough nurses to meet their needs.

"We get calls on a daily basis, and there are a lot of cases we'd like to fill that we can't because we just don't have the staffing," said Angelina Leon, office manager of Independence Home Health in Nineveh, Ind. Her agency sends dozens of e-mails every day to nurses who've posted their resumes on online job search sites. Few prospective job candidates bother to return her e-mails.

"We just don't get many applicants," she said.

Why there's a home nursing shortage

It is no secret that there is a nationwide nursing shortage. Between 2016 to 2026, the Bureau of Labor Statistics says the registered nurse (RN) workforce in the United States will need to grow from 2.9 million to 3.4 million, an increase of 15%. (By comparison, the average growth rate of other occupations during that time period is 7%.) Adding to the challenge of an increased demand for nurses is the daunting projection that one million current RNs will retire by 2030 – at the very same time that an aging baby boomer population will need more nurses than ever. Then there's the nation's low unemployment rate, which makes competition for skilled workers even more difficult.

But Indiana's in-home nursing shortage cannot be explained simply by looking at the national figures. The chronic problem in the Hoosier state runs much deeper than that. And while the nursing and home healthcare marketplace is quite complex, industry insiders say Indiana's worsening home nursing woes can largely be boiled down to two words: lousy pay.

A large number of seriously-ill patients who get home nursing care get it through their state Medicaid program, and each state sets its own Medicaid reimbursement rates for home nursing services. Those rates are the largest factor when it comes to salaries for home nurses, and the rates in Indiana make home nursing look very unattractive.

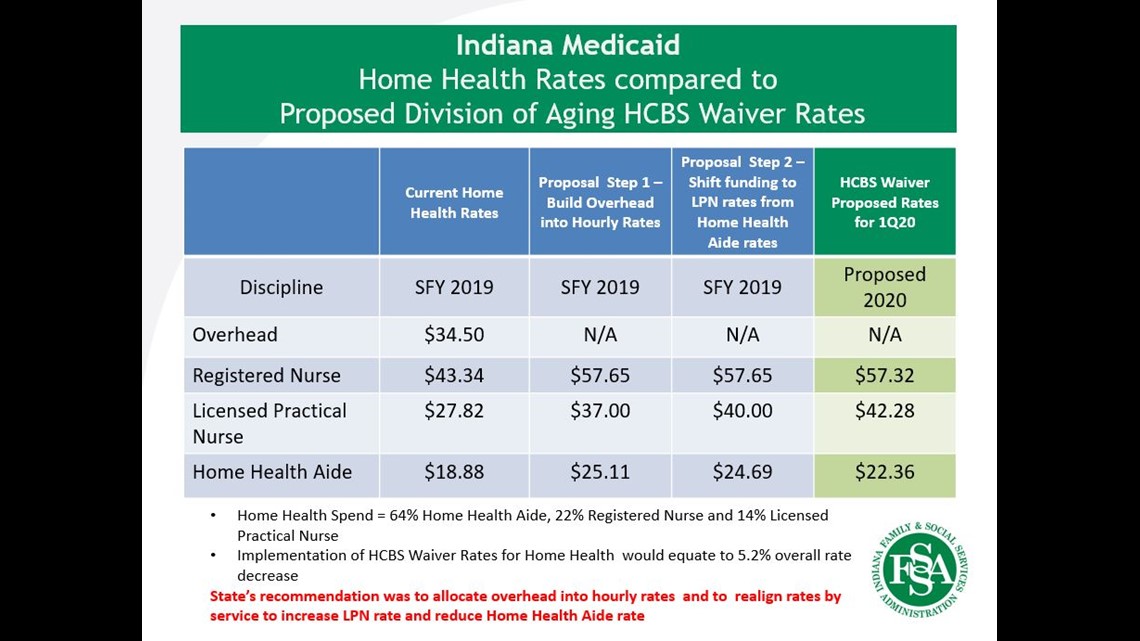

Here's a breakdown: Under Indiana's Medicaid program, the current reimbursement rate for a licensed practical nurse (LPN) who works in home healthcare is $27.82 an hour. That rate is paid to each nurse's state-contracted home healthcare agency, which must deduct its overhead costs for thing such as health benefits, insurance, taxes, training, regulatory compliance, and staff to coordinate case management, scheduling, new patient intake, billing and human resources. After those costs are deducted, the rest (minus a very thin profit margin) goes to the nurse in the form of salary.

It means a licensed practical nurse (LPN) who works in home healthcare in Indiana can make about $19 per hour. That same LPN can easily make $25 per hour working in a nursing home and at least $27 an hour in a hospital, and both of those settings usually offer much better benefits than home healthcare agencies.

While the pay scales are different for in-home RNs and home health aides, the disparity is the same; they can make more money – often much more – in a nursing home or hospital setting than working in a home. And the reimbursement rates for home healthcare nurses have seen only very small increases over the past decade. The state's reimbursement rate for an LPN in 2008 was $26.79 per hour compared to $27.82 in 2019 – less than a 4% increase over the past decade. The state's reimbursement for home health aides is less now ($18.88 per hour) than it was in 2008 ($19.10 per hour.)

It's no wonder home healthcare agencies are having trouble finding nurses and home health aides to meet family's medical needs.

"A lot of the shortage stems from reimbursement rates. It's just makes it an uphill battle to get skilled nurses," said John Cosgrove, administrator at Indianapolis-based Together Homecare. "We can't afford to pay them what a hospital can pay and what nurses are expecting."

Tendercare, one of the state's largest home healthcare agencies, says retaining staff is very difficult under the current reimbursement rate structure. It employed more than 360 home healthcare nurses in 2016. Now it has 257. Its owner says the loss of more than 100 nurses is a direct result of low reimbursement rates, and finding new nurses to replace those who left is very difficult.

"When they come in to interview and you tell them we can pay you $18.50 or $19.00 per hour, they're like going, 'I can't live on that. I'm making $25 at the nursing home.' You just can't compete with that," said Deitchman. "When you have a $1.03 raise in LPN rates in twelve years and home health aides are actually being paid less than they were in 2008, how anybody can think that makes any sense, I don't know."

A recent national survey shows the turnover rate for home healthcare agencies at a staggering all-time high of 82%. Turnover was so severe in 2018, more than half of the home healthcare agencies participating in the survey reported they had to turn away new clients because they did not have enough caregivers.

Nurses face tough choices

The impact of the state's low reimbursement rates impacts not only families seeking home nursing care but also the nurses working on the front lines.

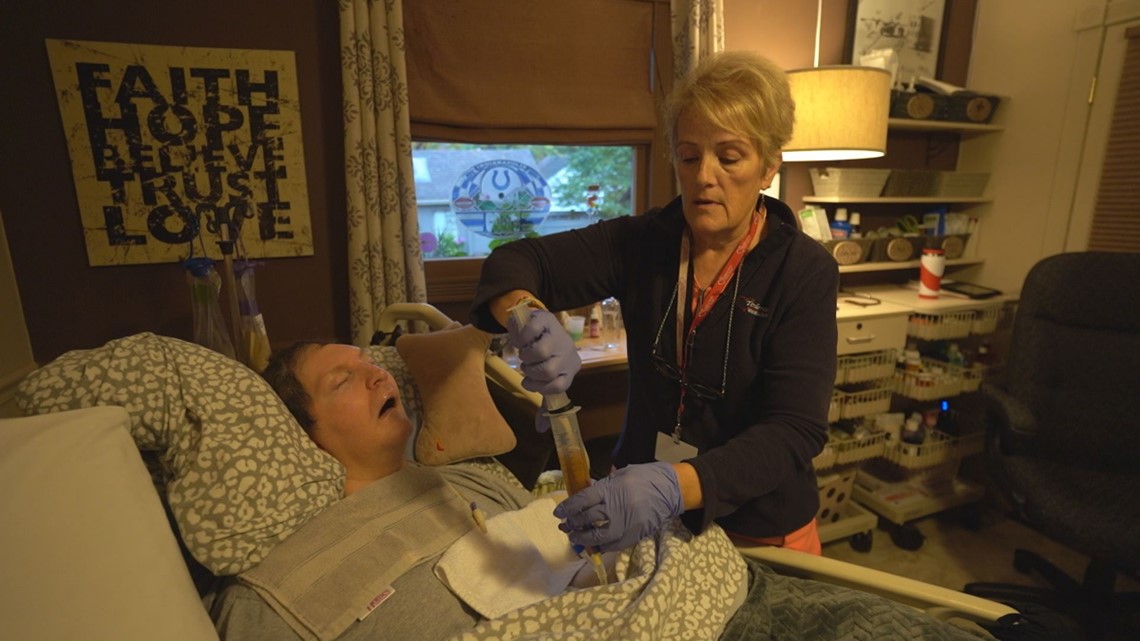

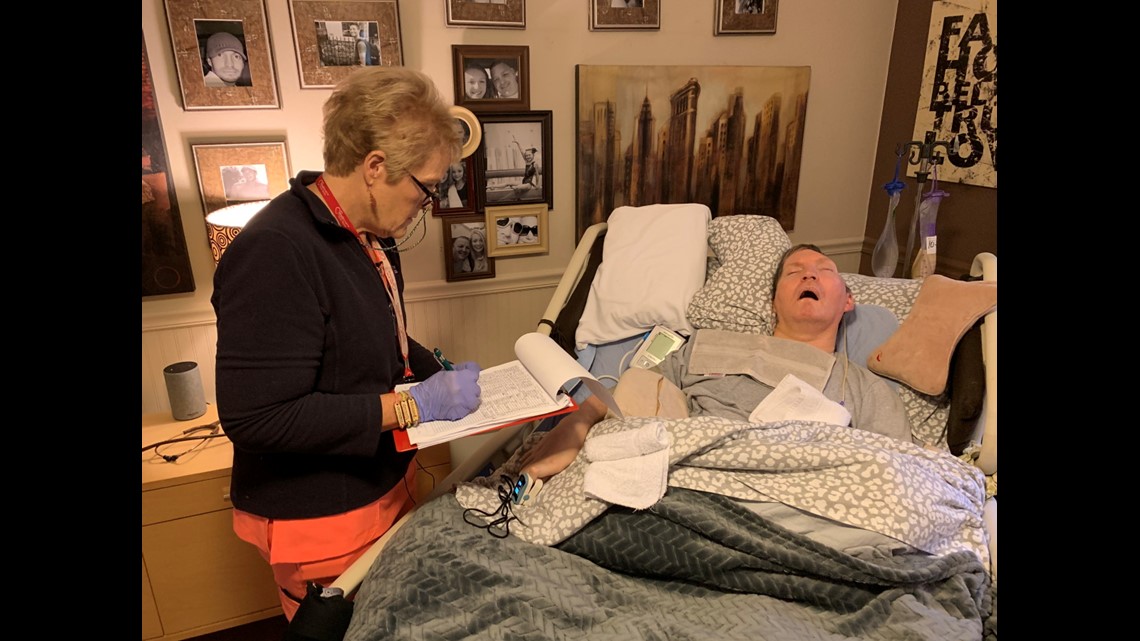

Sue Halvorson is a longtime LPN who moved to Indiana three years ago. She quickly found a home healthcare agency eager to hire her and was assigned to work with a young man named Eric Berry.

"He's great, and his family is just wonderful. It's an honor to care for him," Halvorson said.

The pictures hanging near Eric's bed show a strong, handsome graphic artist who lived a very independent life in Chicago. Then tragedy struck.

"Oh boy, that was probably the worst day of our life," recalls Eric's father, Brian, who just happened to be in Chicago on a business trip when he found his son in the nick of time. "I kicked the door in on the apartment and found him on the couch, just hanging on to life. He was just barely hanging on."

An undiagnosed tangle of blood vessels in Eric's brain ruptured, causing massive damage. Doctors cut away part of Eric's skull to relieve the pressure, saving his life. But the life Eric and his parents knew would never be the same.

"It changed everything, but it didn't change anything, if you follow me," said Brian, sitting alongside his wife, Brenda, and tightly holding her hand. "From day one, after we got him stabilized and he was out of the hospital and in a nursing home, we had one goal, and that was to get him home."

And that's where Halvorson comes in.

She is one of several rotating home healthcare nurses who care for Eric. Halvorson works three 12-hour shifts each week while Brian and Brenda work at their own business. The nurse has plenty to do. Eric is paralyzed from the neck down. His nutrition and medications are delivered through a feeding tube. He does not speak. Once a while, Eric will laugh, providing his parents a glimpse of the fun-loving boy they remember from a decade ago – and a rare chance for his nurses to see a side of Eric they have only heard about.

Halvorson has grown very fond of her patient. She does not want a different job, but lately she has been having doubts about being a home healthcare nurse. Over the past three years working with Eric, she has received a raise of 25 cents per hour.

"Sometimes it keeps me awake at night. I'm single. My rent's going up. Cost of living is going up, and I just had to borrow from my 401K just to make ends meet," she told WTHR. "I feel frustrated. I'm not getting the pay I feel I deserve for being a nurse for 36 years. A couple of housekeepers I know make $25 an hour under the table, so there's no taxes. Here I am at $19.25 and I'm taking care of a person, keeping them comfortable. I don't get it."

Brian Berry doesn't understand it either. He knows the importance of home nursing care for Eric and his entire family.

"It's everything. It's absolutely the most important thing. If we didn't have it we couldn't have had him at home," he said.

The Berrys know firsthand that finding nurses for their paralyzed son can be hard to come by, and they know the state's current formula for reimbursing nurses isn't working.

Halvorson often wonders the same thing.

"You shouldn't have to dip into your savings to do this work. It shouldn't be like that. That's the frustrating part," she said.

Even more frustrating, the state's decision to not improve rates for home healthcare nurses isn't hurting just the nurses and families who struggle to find enough nursing care. It's also hurting the state, costing the Indiana Medicaid program more – not less – because many patients who lack the home nursing care they are entitled to end up right back in the hospital.

Injuries, institutions and deaths

As Tyesha Wright waited month after month to find a home nurse for Desire, she began to get accustomed to her new around-the-clock routine of caring for an infant who relies on a respirator. At times, the rapidly-growing girl with bright eyes and a toothless grin was able to breathe without the help of the machine, and Desire even showed interest in crawling.

Those signs of progress didn't last long. What started as a normal day deteriorated quickly when Wright noticed her daughter was struggling.

"Around 9 in the morning, I noticed she kind of like stopped breathing. The ambulance came pretty quickly, and I had gotten her breathing again by the time they got here," she recalled.

Paramedics wanted to take Desire to Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis. Based on months of caring for her daughter, Wright knew Desire first needed to have her breathing tube replaced, but she said paramedics dismissed her concern and did not want to wait.

"Right before we got to the hospital, she stopped breathing again so they had to do CPR, and then she started having seizures," Wright said, wiping away tears. "They said she stopped breathing for like five minutes, so she lost oxygen to the brain. She hasn't really been the same since."

Would the outcome have been different if a home healthcare nurse had been by Desire's side? Would Desire have needed to go the hospital at all? Her mother will never know, but she does think about it every day.

"I just keep saying like, 'What if?' What if a skilled nurse would have been there? She also would have known we had to change her trach," Wright said, shaking her head and repeating herself as she stared into the distance. "What … ifffff?"

Since Desire first came home from the hospital on March 4, she has been readmitted for several long stays in the pediatric intensive care unit. The price tag for those stays can quickly add up, costing Medicare hundreds of thousands of dollars – far more expensive than the cost of home nursing care.

"They should do something to get more nurses to assist families like me because I know I'm not the only one," Wright said.

That's exactly what the medical director of Riley Hospital's home ventilator program tried to tell state officials last November.

In a powerful letter, Dr. Ioana Cristea reminded state leaders that "many years ago it was determined that it was best for children to be in their homes and not placed in an institution." She went on to say "families are suffering greatly" due to Indiana's lack of home nursing services. In a surprising acknowledgment, the doctor said the Riley Home Vent Team discharged at least 25 children on ventilators from the children's hospital who "did not have any [home] nursing," and that several deaths occurred where parental fatigue played a contributing factor – a dangerous symptom of a home nursing care shortage that often leaves parents getting too little sleep. Cristea blamed the state's "decreasing or stagnant reimbursement for Home Health" for the challenges home healthcare agencies are facing in hiring and retaining nurses for her patients, and she said the resulting nursing shortage has forced some parents to place their children in nursing homes.

"Nobody just wants to give their child up to a facility," Wright said. "When that happens, that's basically the state saying they're giving up on kids like this, and that's not an option for me."

Big pay raises proposed

For years, home healthcare agencies have been working with state lawmakers and Indiana's Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA) to try to address this problem – but with little success.

"They'll tell you, 'Don't worry. We'll fix it in the budget or we'll fix it with new rate methodology.' They always keep telling you that and then they jerk it back, you know?" said Deitchman, the Tendercare owner who has repeatedly discussed low reimbursement rates with state leaders.

Dr. Jennifer Sullivan hopes to change that. She runs FSSA, the agency that oversees the state's $2 billion Medicaid budget, and she knows Indiana is considered one of the worst states in the country for providing quality long-term care.

"I know our numbers are horrible and, quite honestly, we have a lot of work to do in that area to make things better," she told 13 Investigates earlier this month.

Sullivan was talking about a scorecard from AARP that measures the ability of all 50 states and the District of Columbia to provide day-to-day help for frail individuals with disabilities or long-term medical conditions. AARP says Indiana ranks 51st – dead last in the nation – because of its poor affordability and access of long-term care, limited choices for healthcare settings, and inadequate support services for family caregivers.

The secretary of FSSA said supporting home healthcare is a priority for her agency, and she strongly supports home nursing care for individuals who wish to receive their long-term care in a home setting. "Our job at FSSA is to facilitate that choice for as many kids, families, aging Hoosiers as possible to make that choice a real one for them," she said.

To accomplish that goal and to help alleviate the state's in-home nursing shortage, Sullivan told WTHR her agency has asked the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to approve a significant increase in the state's Medicaid waiver reimbursement rates. Those are the rates impacting home nurses who work mostly on nights and weekends to provide caregivers like Brian and Brenda Berry a chance to see their grandchildren and to get out of the house. If approved, the rates for a RN providing home respite care would jump from $43.34 to $57.32 per hour. LPNs who offer respite care would see their reimbursement rates increase from $27.82 to $42.28 per hour, and the rate hike for home health aides would rise to from $18.88 to $22.36 per hour.

Sullivan said the process to raise rates is complex, lengthy and ongoing. "It's not something we're doing in the future. It's something we're doing now," she explained.

It is not clear when or if CMS will approve FSSA's reimbursement rate request. The federal agency has not yet responded to WTHR's questions about a timeframe for completing its review.

Even if CMS does approve the rate increase, it will not impact the reimbursement rates for the many nurses who provide in-home services while caregivers are working or sleeping. Those rates are set under a completely separate plan, known as the state pre-authorized Medicaid (P.A. Med) Home Health program. FSSA says it reviewed and increased those rates in 2017 and cannot seek another increase in funding right away.

"Adjustments to the Home Health rates would need to be ready to propose for the next biennium budget, which would be the 2021 budget," Sullivan told WTHR.

Nurses dispute FSSA's suggestion that the agency raised P.A. Med reimbursement rates just a few years ago, pointing out the small increase awarded in 2017 simply reversed a rate cut that FSSA had implemented two years earlier. They are frustrated that the average annual .35% (approximately one third of one percent) rate increase offered to Indiana LPNs over the past 11 years falls well below the 1.8% average annual rate of inflation during that same time period.

Following WTHR's interview with Sullivan, an FSSA spokeswoman contacted 13 Investigates to explain the agency is now re-examining its P.A. Med reimbursement rates for all in-home nurses.

"The state has been working on an interim solution to address state plan nursing pay, particularly among licensed practical nurses, reviewing the methodology used for setting home health rates and has proposed an alternative to the home health industry that would align state plan rates closely with the proposed waiver rates," wrote FSSA deputy communications director Marni Lemons. She said FSSA hopes to implement higher rates as soon as January but is now waiting on stakeholders to review the proposal.

The interim solution that FSSA shared with WTHR shows the state agency would not allocate more money to in-home nursing, but rather shuffle existing P.A. Med reimbursement money in an effort to increase the take-home pay for both skilled nurses and home health aides working in home healthcare. The plan includes eliminating an "overhead" payment for each visit from an in-home nurse. That $34.50 per visit overhead payment would instead be rolled into higher hourly wages. Under the proposed FSSA plan, the home RN reimbursement rate would increase from $43.34 to $57.65 per hour. The LPN reimbursement rate would jump from $27.82 to $37.00 per hour. And the state's home health aide rate would increase from $18.88 to $25.11 per hour. In step two of the plan, FSSA would slightly reduce the reimbursement rate for home health aides (down to $24.69 per hour) in order to add an additional $3.00 in reimbursement for LPNs, bringing their rate up to $40.00 per hour.

If approved and implemented, the reimbursement rate increases now being proposed by FSSA could translate to an immediate pay increase of $5 to $7 per hour for home healthcare nurses across the state. Agencies like Tendercare welcome what they consider to be a long overdue rate adjustment. But some industry experts are skeptical that the increases will have much of an impact on the nursing shortage.

"Is it enough to offset what a nurse can make in a hospital or institutional setting? No, I don't think so," said Chad Bales, assistant director of case management at CICOA.

The non-profit agency oversees state and federal funds to provide advocacy and support services for seniors, the disabled and family caregivers across eight counties in central Indiana. It also helps facilitate home nursing for those who need it, and at any given time, the agency maintains a waiting list of at least 50 people searching for in-home nursing care.

"We really try to keep people at home rather than sending them to an institution. That's definitely their preference, but it's one of the hardest services we provide because it's so hard to find nurses," Bales said. "The rate nurses can get in a hospital, they're still going to flock to those places because they get paid so much more. Even with the raise, I don't anticipate it will get better anytime soon."

A lawmaker who understands

The other option for increasing salaries for in-home nurses is for state lawmakers to allocate money for a pay raise.

Sen. John Ruckleshaus (R-Indianapolis) proposed a measure earlier this year that would have earmarked millions of dollars for better pay for home healthcare nurses. It did not succeed.

"We had allocated $20 million for this, and unfortunately in conference committee things happen all the time," the senator said. "That money was given to other areas of the budget."

Ruckleshaus knows all about the need for home nursing care. He has a quadriplegic son and says he understands what other parents of children with special needs are going through.

"Yeah it hits home. Very, very personal to me and I completely get it," Ruckleshaus told WTHR.

Asked why the state legislature has repeatedly failed to approve increased funding for home healthcare, the senator said he believes most of his colleagues do not appreciate what children like Elias and Desire are experiencing – and the impact on their families.

"I think honestly there's probably a handful of us that truly understand this issue on a personal basis," he said. "This is reality. This may not be the norm they see on a daily basis or what they've been exposed to, but this is something we need to do. It's our job to help them."

Because state lawmakers did not specifically approve more money for home nursing care in the current 2-year budget the governor signed this spring, it would appear that no additional state funding would be available until the General Assembly considers and approves its next budget in 2021.

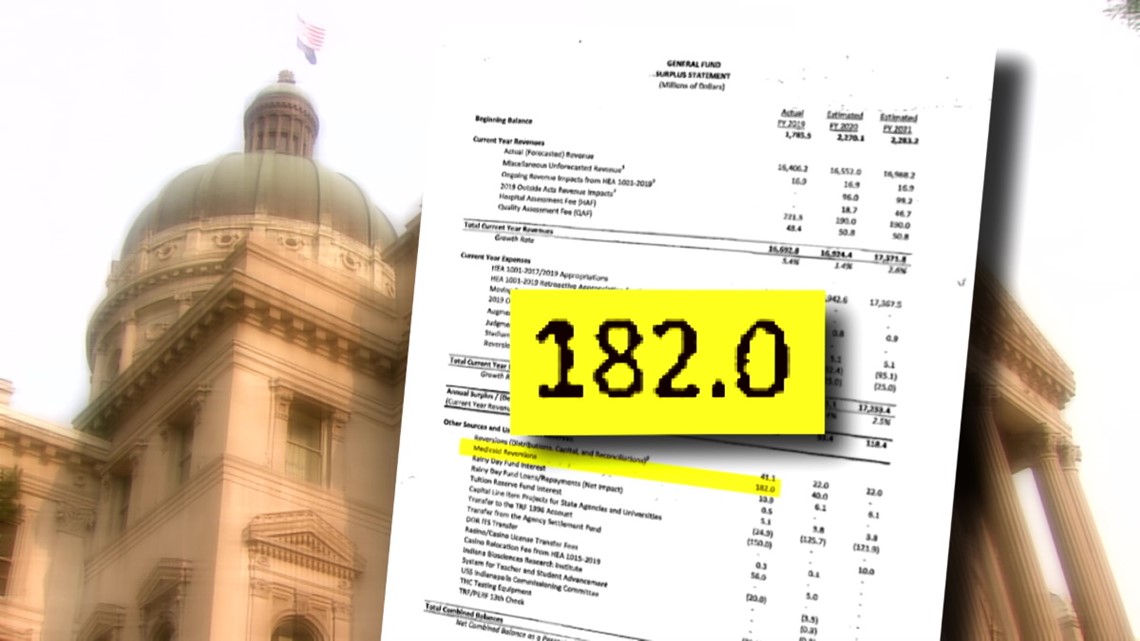

But appearances can be deceiving – especially if you don't look very closely at the state's balance sheet, which shows the state of Indiana has been setting aside hundreds of millions of Medicaid dollars and diverting the money for purposes other than healthcare for the state's most vulnerable citizens.

$182 million in healthcare funding unused

Touting years of fiscal responsibility, the governor and many state lawmakers proudly boast of Indiana's surplus, which now exceeds $2 billion. The reserves set aside in the state's General Fund put Indiana in a financially-stable position in the event of an economic downturn, while also giving state leaders flexibility to spend the additional dollars in areas of urgent or unexpected need.

13 Investigates has learned a big slice of that surplus comes from FSSA – specifically, unused Medicaid money that could be used for home healthcare if state leaders want to do so.

This year alone, FSSA gave back $182 million dollars of unused Medicaid funds that were sent straight to the state's General Fund to pay for things like highway projects and a new barn for pigs at the Indiana State Fairgrounds. The State Budget Office has already earmarked another $40 million of the unused Medicaid money to be sent to the General Fund next year, according to a General Fund Surplus Statement obtained by 13 Investigates.

Underpaid nurses and families desperately seeking home healthcare are frustrated to learn money paid by Medicaid is not being spent to help alleviate the state's severe home nursing shortage.

"It's a shame that Indiana is behind on this because we're one of the few states that actually has money," said Brian Berry. "We have a state that has a surplus, and they need to use some of it on things that need to be corrected."

"I just see monies being used in places where it makes no sense," added Halvorson.

FSSA has not responded to WTHR's questions about the exact amount of unspent Medicaid dollars it discovered this year. But its deputy communications director told WTHR that surplus dollars are "routinely" returned to the General Fund and "if any of these dollars go unspent … then we work with the State Budget Agency and Office of Management & Budget to determine how those funds should be used."

While Lemons, the FSSA communications deputy director, told 13 Investigates "any increases in total expenditures would need to be included in the next biennial state budget," the state's actual budget says something different.

According to the budget, if the money allocated by state lawmakers for Medicaid obligations and administration is not sufficient to meet those obligations, "then there is appropriated from the general fund such further sums as may be necessary for that purpose, subject to the approval of the governor and the budget agency."

In other words, the governor and State Budget Agency can use surplus money from the General Fund to meet urgent needs of the state Medicaid program, even if those dollars are not specifically earmarked by state lawmakers.

WTHR contacted the governor's office to discuss the state's severe home nursing shortage. When his staff did not reply after several weeks, 13 Investigates met the governor at a public event to ask some questions – including whether he would consider spending some of the recently-reverted $182 million in unused Medicaid funds to supplement higher reimbursement rates for in-home nurses.

"We do have funds that could be allocated in areas of high need," Gov. Eric Holcomb told 13 Investigates. "We just need to know the exact people and make sure we are shepherding them to the right resources if they're available."

The state does have resources, but it also has a troubled track record of not making those resources easily accessible to its most vulnerable residents. When it comes to in-home nursing care, no one illustrates that spotty track record better than a woman who recently won a federal lawsuit against FSSA.

State loses home nursing lawsuit

Going home at the end of the day is something many of us take for granted. Not Karen Vaughn.

She recently fought a three-year battle against the state of Indiana simply for the right to roll her wheelchair into her living room and to sleep in her own bed at night.

"Sometimes you think, 'Why? Why do I have to fight so hard? Why don't they see this is the right thing to do?'" she said. "It just makes no sense."

Vaughn's fight began when she was shot in the neck at the age of 18 and, at that moment, was paralyzed from the neck down.

Since then, she has lived a remarkably full and independent life: working, serving on community boards, and advocating for other Hoosiers with disabilities. That lifestyle took a hit in 2016, when Vaughn developed pneumonia, resulting in a trip to Methodist Hospital. Doctors performed a tracheotomy to help her breathe, meaning she'd need more frequent nursing care rather than the brief visits from home health aides that she had received from home health aides.

But what should have been a one-week or two-week hospital stay soon turned into months – and then much longer than that. She was admitted to Methodist hospital in 2016. She would not return home for three years because nobody could find a home healthcare nurse to help Vaughn at her apartment.

"They don't have enough nurses. They don't have that for anyone because they don't pay enough," she told WTHR.

Eventually, the hospital told Vaughn she had to leave. After all, it is a hospital – not a hotel – and doctors were convinced she didn't need to be there. They said she could live comfortably at home with nursing care – care that Medicaid was willing to pay for.

But since there were no nurses willing to work in Vaughn's home at the rates the state was willing to pay, she was instead sent to a nearby nursing home. She soon developed horrible bed sores and infections that put Vaughn right back in the hospital. When the she recovered, nursing care still wasn't available, so Vaughn was sent to another nursing home, against her will, that was an hour away from her family and friends.

"I wanted to live a life. I wanted to have a life. You don't do that when you're in a facility. You don't live there – you exist," Vaughn said.

It was at that point that she filed a lawsuit in federal court, claiming the state of Indiana and FSSA were essentially holding her hostage in hospitals and nursing homes in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The judge agreed and issued a scathing order that said FSSA "failed (its)moral test" to care for the state's most vulnerable citizens. In her order, Chief Judge Jane Magnus-Stinson of the U.S. District Court Southern District of Indiana wrote FSSA was stuck in a "bureaucratic quagmire" that even its own employees couldn't explain. She said the state agency discriminated against Vaughn, and criticized FSSA for arguing that it could essentially "set its reimbursement rates so low that ... individuals [on Medicaid] would all be forced into nursing homes."

Frustrated at the state's lack of effort and follow-through to help secure in-home nursing care for Vaughn, the federal judge declared "if the defendant will not act to protect Ms. Vaughn and her civil rights, then the court will."

"That's an awesome judge," Vaughn says smiling after hearing the judge's words read aloud." Her first thought when she learned of the ruling?

"I get to live," she said.

The federal court ruling was issued in January 2019. Vaughn moved back into her downtown apartment a few weeks later, and FSSA is now legally required to ensure she has home nurses around the clock. Constant care is necessary to clear Vaughn's breathing tube whenever it gets blocked – something she cannot do by herself since she is paralyzed.

It's just the latest triumph in a life full of victories for Karen Vaughn – but the ruling is bittersweet, as well.

Vaughn thought her court case would mean other vulnerable Hoosiers would now also get easier access to home nursing care. After learning about families like the ones interviewed by WTHR, she now realizes FSSA has not yet changed much at all.

"It breaks your heart," she said. "How can the state of Indiana justify doing to their families what they do? How? Why?"

Vaughn also realizes her court victory might be short lived. FSSA is now appealing the case, meaning the state might not have to ensure that Vaughn gets home nursing care after all.

Asked why the agency has chosen to appeal the case, FSSA secretary Dr. Jennifer Sullivan said she cannot comment because the legal case is still active.

For some Indiana families who care for loved ones who have special medical needs at home, the appeal makes them question whether the state really is serious about providing better access to home nursing care. They also wonder whether state leaders are really listening and whether they are aware of their daily struggle for survival.

"I get the sense they've given up on our kids," Wright said. "Like do they even care? It doesn't seem like they care."

Families living in rural parts of the state have the same concerns. They say access to home healthcare resources is even worse than in Hoosier cities and suburbs.

Going to great lengths to find home nurses

The Sterrett family in Delphi, Ind., feels the impact of the state's home nursing shortage every day.

Shirley and Luther Sterrett spend much of their day – and night – caring for their son Josh, who was diagnosed with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy when he was seven years old. The cruel, incurable disease weakens muscles all over his body.

"He can't take deep breaths. He can't cough, so we have to suction him. It's not that taking care of Josh is hard, but there's mental strain because you can't be a more than a room away," said Shirley.

"Yeah, if you go outside for a few minutes and something happens to Josh, he's probably not breathing by the time you get back," added Luther.

The avid fan of Western movies and Purdue University sports has beaten the odds that doctors gave him as a young boy. They told Josh's parents years ago that their son's life expectancy was 18. He is now 39 – thanks, in large part, to constant home medical care provided by his parents.

Sitting on the couch talking with a reporter is the most time Shirley and Luther will get to spend together all day. Shirley leaves early in the morning to deliver mail for the U.S. Postal Service while Luther takes care of Josh at home. As soon as Shirley gets home, Luther heads off for his nightshift at the Subaru assembly plant in Lafayette, and it's Shirley turn with their son.

And if they are lucky, a home healthcare nurse will come to give them a helping hand so Shirley and Luther can each get at least a few hours of sleep. The Sterretts are supposed to get 92 hours of home nursing care every week, but they don't. Often, it's just a fraction of that because there just are not enough nurses to cover all the hours. When nurses are scheduled, they can't always make it.

"If a nurse doesn't show up, then you're the nurse," Shirley said. "Luther will work all night, stay up with [Josh] all day, and then he'll go to work that night, so he goes without sleep all that time. You miss work or go without sleep, that's the way it is."

And that happens frequently enough that Shirley has used all her vacation days and personal days and sick days. If she were to take another day off, Shirley worries she'll lose retirement benefits she's been earning for more than 30 years.

"I need my dental surgery. I can't do it. I have cataracts. I need my cataract surgery. I can't do it 'til I retire because I'm out of time," Shirley told WTHR. "It's not like we don't work. We both are trying to earn a living here. We're both trying to be productive citizens and all that, and we need help!"

The help the Sterrett family does get, they're very grateful for.

Doris Crites is a retired RN with lots of hospital experience. Several years ago, she shifted to home nursing, and she loves it. The 85-year-old nurse is one of the closest skilled care nurses to the Sterrett home who's available to work the hours they need. She drives 85 miles each day to care for Josh.

"It is quite a ways. It takes about an hour because I live out in the country, she said. "I really don't mind driving."

If Crites does not make that drive, well, it means Josh won't have a nurse tonight.

That's just how it is in rural communities across Indiana, where the state's home nursing shortage leaves some families with few options.

The good news for the Sterretts: so far, they've been able to find a way to keep Josh at home. The bad news: a severe home nursing shortage means, for years, Shirley and Luther have essentially been trapped at home with him.

"Imagine not being able to walk out your front door. Imagine not being more than two rooms away. It's hard," Shirley said. "I'd love to go outside and plant some flowers, but you don't get to go outside. you don't get to do that."

Governor's response

Other families feel they are in the same position.

"We haven't had a date night since May," Natasha Boling said.

"It shrinks the area of our world. We can't travel," agreed Brian Berry.

Making it to the Statehouse is not easy for these families and nurses, but they hope state lawmakers and decision-makers might still hear their voices anyway.

"I want them to understand it's important, that we need the funds for these nurses because without them, we are suffering and our kids are suffering," Wright said.

"The governor keeps saying he wants to put people first. This is his chance because these kids and families are in crisis," added Deitchman.

The governor told 13 Investigates he is interested in the issue. "Our administration absolutely cares about this home healthcare desire for every Hoosier," Holcomb said. Asked if he would be willing to visit Wright and other families currently impacted by the state's home healthcare shortage, the governor said yes.

"Sure. I would. That's how we're best informed and what this administration does each and every day. Absolutely," he said.

So far, none of the families interviewed by 13 Investigates have been visited by the governor, and his staff has not returned WTHR's phone calls or e-mails to follow up on the governor's apparent willingness to better inform himself on the dire situation facing families across the state.

Dr. Sullivan, who also expressed interest in meeting some of the families highlighted in WTHR's reporting, personally contacted Wright by phone just days after 13 Investigates told her about Desire. The FSSA secretary pledged her agency's help for families in need of home nursing care, and Wright says FSSA has since expressed interest in finding home nursing care for Desire. For now, the little girl is still waiting for home nursing care – 260 days after she was first released from the hospital.

"You can't do it all alone," Wright said, acknowledging that Indiana's lack of home nursing care has left her to do just that. "It's stressful, and it's depressing, and it's unfair all the way around. Our kids deserve better than this."