INDIANAPOLIS (WTHR) — Months after state officials pledged to help families in desperate need of in-home nursing care, those families say they are still waiting for help. And the state appears to have no plan to address a statewide home nursing shortage that has reached crisis levels.

13 Investigates helped expose that crisis with its Gasping for Care series broadcast in November. WTHR's news reports and documentary highlighted Hoosier families who are struggling to find home nursing care that has already been ordered by doctors and authorized by the state's Medicaid program. The struggles are due to a chronic shortage of home nurses and health aides across Indiana, and the home healthcare industry says that shortage has been greatly worsened by the state's low reimbursement rates for home nursing care. Most of Indiana's reimbursement rates for home nurses have barely budged over the past decade, forcing thousands of nurses to leave home healthcare for jobs at hospitals, nursing homes or outside the healthcare industry.

The impact on Hoosier families is often dire. WTHR showed some Hoosiers have been forced to quit their jobs and take on the role of a primary medical caregiver for a loved one due to a lack of home nursing care. For others, the shortage means children and seniors are trapped in a nursing home even though their doctors say they would be better served at home with in-home nursing care. And WTHR's investigation revealed several Indiana children died after they were discharged from a hospital and sent home without adequate home nursing care that the state had pre-authorized.

Indiana's Family and Social Services Administration told 13 Investigates it would intervene to find help for families that cannot get the home nursing services they are entitled to receive.

"We pledge every day to make sure those families are getting the services they need," FSSA secretary Jennifer Sullivan said in November. "We are here to be a voice and a connector for Hoosiers in need of help."

The governor pledged his support as well and said he took immediate action after learning of WTHR's reporting.

"When you brought that forward, my call within five minutes was to the FSSA and [I] said, 'Get with each of these families and figure out what the individual circumstances are so that we can work with them,'" Governor Eric Holcomb told WTHR in early December. "We have to manage them on a very personal 1-on-1 basis."

Help never materialized

All of the families featured in WTHR's Gasping for Care report did get a call from FSSA, just as the governor directed. But each of the families says the purpose of the phone call was unclear.

"I'm not exactly sure why she called us," said Brenda Berry after receiving her phone call from FSSA. Berry's quadriplegic son, Eric, requires daily home nursing care, but the family has lost multiple nurses who left for higher-paying jobs. "The lady who called didn't really talk about better pay or higher rates. But at the end of the call, she did say, 'Give Eric a hug for me,' which I thought was kind of strange."

"Yeah, they called, but I don't really know the point. They didn't talk about getting more hours for Josh," said Luther Sterrett, who also got a phone call from FSSA after his son was featured in WTHR's documentary.

"I don't think they were really calling to help. I think they were calling to say they called," said Tyesha Wright, who has now been waiting nearly a year to receive home nursing care for her daughter Desire. The 1-year-old Indianapolis girl relies on a ventilator to breathe. She was released from Riley Hospital for Children last March because her doctors were told the state had pre-authorized Desire for 80 hours of home nursing each week to monitor her complex medical needs at home. Ten months and hundreds of phone calls later, Wright has not been able to find a single home nurse to work with her daughter.1

Despite FSSA and the governor promising two months ago that "we'll work with them to make sure they get the care they need and deserve," none of the families profiled in Gasping for Care has gotten more nursing care. Some have gotten less, and others Indiana families are at risk of losing the nursing care they've got.

No nurse = no school

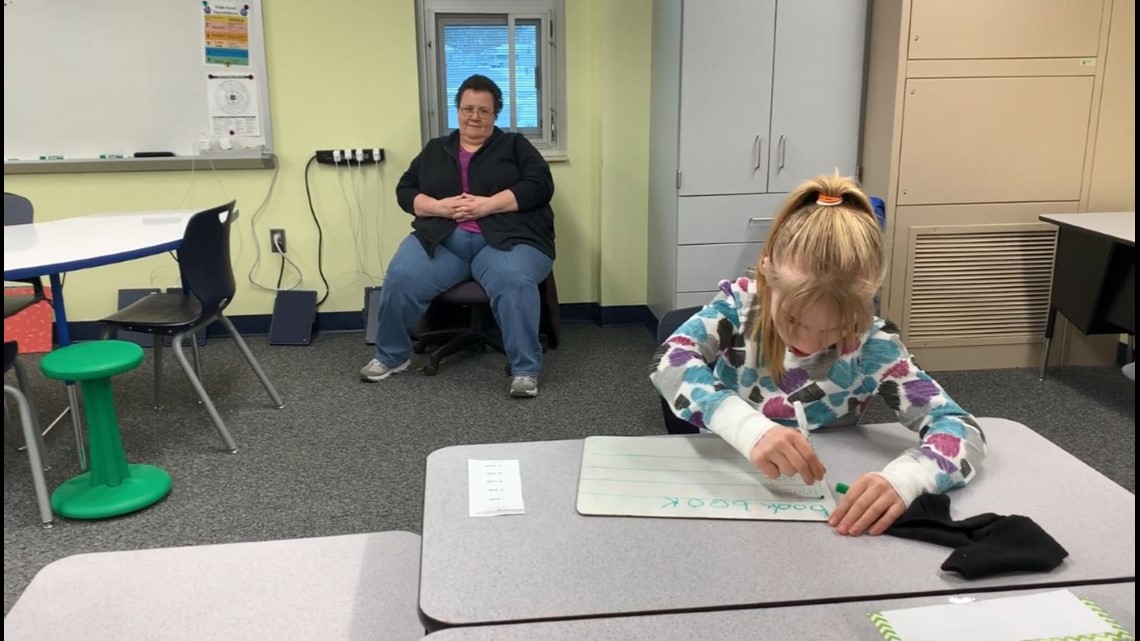

Sheila Pitts was born with mitochondrial disease, a genetic disorder that affects her nerves and muscles, resulting in chronic physical and developmental delays. The Greenfield girl also suffers frequent seizures. She takes 13 medications and currently has a team of seven doctors, who say Sheila must have trained medical staff nearby in order to attend school.

"The reality is she's got to be watched 24-7," said her mother, Detra Craft. "If Sheila doesn't have a nurse, she does not go to school. It would be too dangerous because [her health] can change very fast."

The state has pre-authorized a home-based nurse to attend school with Pitts every day, and the 10 year old with light blue eyes and a blonde pony tail adores her time at Greenfield Intermediate School, which is less than a mile from her home.

"Sometimes when my nurse doesn't make it, I just stay home. I'd rather be at school," she told WTHR.

But Craft recently received a discharge letter from the family's home heathcare agency stating that the fourth grader's nursing care would be ending. Craft says the nurse who had been accompanying Pitts to class this school year was not dependable – forcing Sheila to miss 16 days of school before winter break – and when that nurse left the agency, no one else was available to take her spot.

"They said they don't have enough help," Craft explained. "There's no funding for these nurses. With no nurse, I'd have to pull her out of school and quit my job to homeschool her."

Representatives from Advantage Home Health Care told WTHR they had little choice but to notify Craft that her daughter's home nursing care would be suspended.

"We did have to issue a discharge letter," said executive director Jennifer Heine. "We were not able to provide the hours needed. We have a very high turnover."

Advantage is one the largest home nursing agencies in the state, and it has struggled to attract and retain its nurses and home health aides.

"Because of the reimbursement rates, they're able to go down the street to McDonalds or Hardees and make more money than they could in home care," Heine said.

"It's kind of the perfect storm right now," said Advantage owner Paul Holeman. "Not only do we have a greater number of people who are in need of service, we have fewer people to provide it. While the demand exists, the ability to meet that demand does not because we don't have the staff to do it. We're just not competitive as far as wages."

It means Pitts is not the only patient getting a discharge letter.

"I've talked to four families this week, and it's heart wrenching," Heine said.

Advantage has been able to find a temporary fix. A home healthcare nurse who lives in Muncie has agreed to drive two hours roundtrip every day so Pitts can continue to attend school in Greenfield. The discharge letter has been rescinded – for now. Advantage does not know how long that solution will last.

Home nursing crisis is growing

Other home nursing agencies are in the same position.

Indianapolis-based Tendercare, another large home healthcare agency in central Indiana, says it has recently lost more than 100 nurses who left to take other jobs with higher pay. The agency has also had to turn away more than 200 patients due to the nursing shortage. Each of the past three years, Tendercare says it canceled more than 50,000 hours of home nursing care that the state authorized (and was willing to pay for) because there simply were not enough nurses to meet patients' needs.

"Yeah, it's heartbreaking when you see these families are in crisis and you can't help them," said Tendercare owner Leslie Deitchman. "It's because of the pay structure, and it's very sad. Home health aides are actually being paid less than they were in 2008 right now. How anybody thinks that makes any sense, I don't understand it."

Across the state, the demand for home nursing is rising quickly while the pay for home nursing isn't going anywhere.

"The combination of those two things has created a crisis level within the industry itself," acknowledged Evan Reinhardt, executive director of the Indiana Association for Home and Hospice Care. "It's tragic and these are things we've been communicating to the administration for a number of years now."

The trade association has been pleading with state leaders to increase reimbursement rates for home nurses across the board, but Indiana lawmakers rejected calls to do that in last year's budget. FSSA and the governor's office say they cannot increase funding this year because 2020 is not a budget drafting year for the Indiana General Assembly.

"Adjustments to the home health rates need to be ready to propose for the next biennium budget, which would be the 2021 budget," said FSSA secretary Jennifer Sullivan.

But the administration does have more flexibility to act than it is publicly acknowledging.

Millions of dollars unspent

While state officials claim they cannot immediately address the home nursing crisis, Indiana statute and the state's financial ledgers suggest otherwise.

First, the state's budget includes a provision that clearly allows the governor, the State Budget Agency and FSSA to direct additional funding for Medicaid-related spending if the budget is not sufficient to meet the needs of the state's Medicaid obligations.

Second, the state has a huge surplus of unused Medicaid money available to tackle pressing healthcare needs like the home nursing crisis.

In November, WTHR reported that state leaders were planning to divert $182 million of that Medicaid surplus to unrelated projects, such as highway construction projects and a new swine barn at the Indiana State Fairgrounds. But an internal document obtained by 13 Investigates shows the amount of Indiana's Medicaid surplus is much larger than originally thought. The State Budget Agency spreadsheet, presented at a closed-door meeting last summer, reveals Indiana ended 2019 with nearly $350 million in unspent Medicaid funds built up over the past five years. It is money the state had originally budgeted to provide much-needed healthcare for vulnerable Hoosiers, but most of those dollars are now being re-directed for state expenses that are unrelated to healthcare.

Reinhardt says he was not informed of the $350 million Medicaid surplus when his trade association was at the table last fall with FSSA negotiating for higher reimbursement rates for home nurses. Instead, FSSA and state budget officials told home health agencies that any proposed rate changes would have to be "budget neutral." That means the administration did not want to spend any additional money for increased home nursing rates, and any proposed rate hikes for in-home nurses would have to be offset by equal funding cuts that would impact other home healthcare workers.

"That puts us in a very difficult situation. We think not only is there significant money available to make the changes we'd like to make, but we think those changes in the aggregate will save the state dollars," Reinhardt told WTHR. He said because providing nursing care in a home setting is often less expensive than in a hospital or nursing home, state taxpayers would benefit by shifting more Medicaid dollars to home healthcare.

The governor does have the ability to spend the state's Medicaid surplus anytime he want in order to fix a statewide home healthcare crisis. Asked directly by WTHR whether he is willing to do that, the governor suggested he is not.

"FSSA will continue to work with those families to see if we can accommodate and satisfy what their needs are on a case-by-case basis," the governor replied.

Governor defends his position

The governor's plan to help individual families on a case-by-case basis has not been effective. The isolated phone call from FSSA to four families who are lacking adequate home nursing care had no impact, and the state seems to have no plan to help thousands of other families across Indiana who are in desperate need of a home nurse.

The governor told 13 Investigates any plan to address the crisis must be financially responsible, indicating he is not a fan of spending surplus dollars as a long-term solution.

"The last thing we want to do is create a cliff to where it drops off and then there is no resources there in the future for more families," he said. "We're operating under a framework that has to be sustainable."

That response does not sit well with some state lawmakers, like Rep. Greg Porter (D – Indianapolis).

"You're going to calculate someone's health for sustainability? Doggone it! I'm tired of that. We're better than that," Porter said in disgust.

As a voting member of the state Budget Committee, Porter believes the state's large surplus should be used to confront the home nursing crisis now, rather than waiting for another budget cycle to address it in 2021.

"We have the money to be able to tackle this problem… There's no doubt in my mind those dollars are there, and the legislature has to take care of its citizens," he said.

State Budget Director Zac Jackson told WTHR he believes Indiana leaders should be cautious in how they use the state's surplus funds, which now exceed a combined $2 billion dollars.

"Since the surpluses represent one-time leftover dollars and not an ongoing funding source, we have to be very careful when deciding to use surpluses (one-time) to fund (ongoing) rate increases," he told WTHR in an e-mail. At the same time, Jackson acknowledged that Indiana has had a significant Medicaid surplus in each of the past five fiscal years. Some of that surplus – about $21 million – has been earmarked for increased rates for respite care provided by home nurses. But that increase has not yet been approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and if it is approved, the majority of in-home nursing provided in Indiana will still fall under a much-lower reimbursement rate structure.

Yet the governor remains convinced that families needing home healthcare can find it despite Indiana's low reimbursement rates for home nurses.

"The important thing is we have to working with these folks to meet their needs right now," he said. "And we'll continue to work with them this week – not next year. We need to work with them this week."

But this week doesn't look any different than last week for families all over the state. They still cannot get the level of home nursing care they need – largely because the state's low reimbursement rates for home nurses have turned a home nursing shortage into a home nursing crisis.

"It's not tomorrow. It's not 2021. The crisis is today," Reinhardt said. "We need to advocate for more money in the system."

"Indiana really needs to look at what they're doing because these children need the help, and they're not getting it," agreed Craft. "I think it's unfair to the children and the families that are suffering."

1 Despite not getting promised assistance from FSSA or the governor's office, Tyesha Wright believes she has finally found some home nursing care for her daughter. She told WTHR that with help from the Tendercare home nursing agency, she hopes to have a home nurse working with Desire three days per week by the end of the month. While that is much less than the number of hours the state has pre-authorized for Desire to receive, Wright hopes it will eventually lead to the full-time nursing assistance her family needs.