GREENFIELD, Ind. — It's been almost eight years since Jeana Horner and her husband Jack wound up in a fight to get their cars back – confiscated by police for a crime they say they had nothing to do with.

“I had done nothing illegal, and yet they got to keep my cars anyway,” said Jeana.

Making things even harder, her husband's car had a handicapped plate on the back of it.

“We had to go buy another vehicle so he could get around. That’s how bad it was,” she said.

Jeana’s son had been borrowing their cars while his mom and step-dad were on vacation. He was pulled over one night and officers found marijuana inside.

Both vehicles were confiscated by police. Horner said it took eight months and a judge to get them back. Her son’s charges were eventually dropped.

“What happened was wrong. It was my stuff. I had no idea what my son was doing,” she said.

The law allows law enforcement agencies to take property, sell it and keep almost all of the money as long as it was most likely connected to a crime.

Critics have long called the practice “the greatest threat to property rights in the nation.”

Supporters call it an impactful crime-fighting tool. Others are somewhere in between.

Support for civil forfeiture

Supporters of civil forfeiture say it’s a useful way to put a dent in criminal enterprises. They say it puts a dent in the illegal drug trade by taking away a dealer's profits or their vehicles.

“Sometimes you find with defendants that … a lengthy sentence isn't enough if they can get out of jail and cash in on all the money they made on their crimes,” said Hendricks County Prosecutor Loren Delp. “Have there been nightmare stories in other jurisdictions? Absolutely. And no prosecutor wants to engage in any of that. It's really ‘how is it that we prevent crime from being profitable?’”

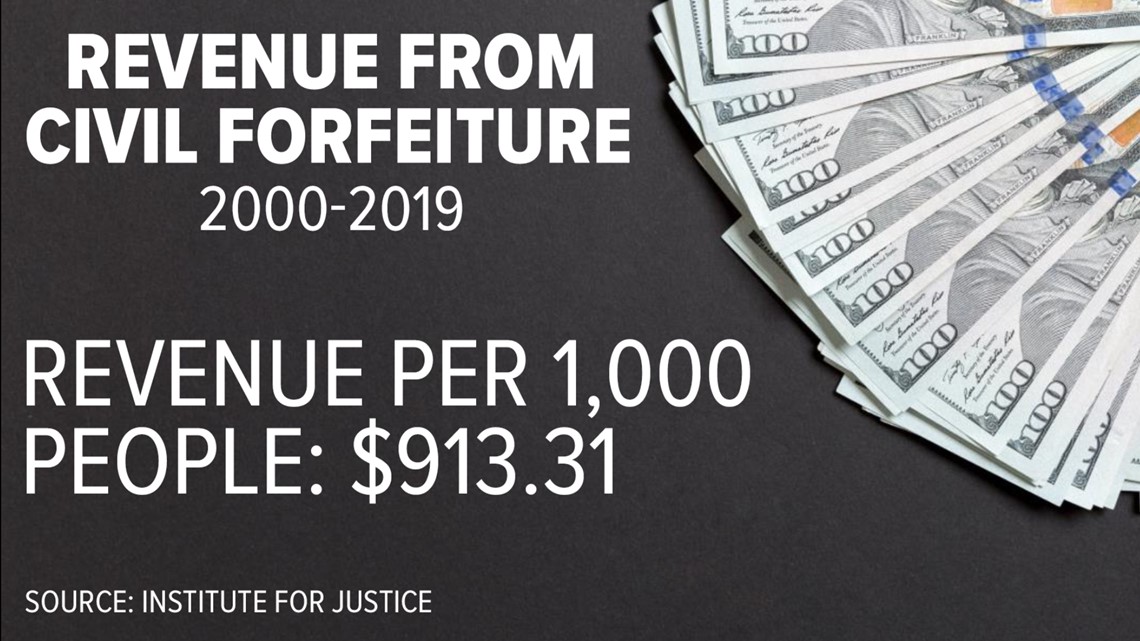

Forfeiture brings in billions

According to the Institute for Justice, civil forfeiture revenues topped $69 billion between 2000 and 2019. That includes $115 million from property owners in Indiana.

About 90 percent of that money can be used for law enforcement budgets – including the cost to reimburse them for the cost of working the case. The remaining money must go to the Indiana Common School Fund.

But critics call that an incentive to police for profit.

“(Defendants) don’t have to be charged with a crime,” said Jennifer McDonald, a research analyst with the non-profit organization Institute for Justice.

And McDonald and her colleagues say even if you are charged with a crime, the punishment of taking your property can be harsher than the crime itself.

They point to Tyson Timbs of Marion.

Timbs case

Tyson Timbs admits he’s made some wrong turns in life. But nothing that should’ve cost him his car.

“Our system is supposed to be about rehabilitation,” said Timbs. “That's not what any of this is.”

Timbs pleaded guilty in 2013 to heroin charges. He served home detention, got probation and paid several hundred dollars in fines.

Police then seized his Land Rover, claiming Timbs has used it to traffic drugs. And that’s when Timbs said he went from criminal to victim.

“We already came to an agreement in court what I would do, with probation and all that,” he said outside a Grant County courtroom in February, 2020. “And then they throw this is on.”

Timbs had bought the Land Rover months before with proceeds from his father’s life insurance policy.

“And if someone like me is supposed to be trying to rehabilitate myself and reintegrate myself into society, what sense does it make to make it harder?" he asked.

Timbs’ legal team said forcing Timbs to forfeit his $42,000 Land Rover was excessive, given the crime. They say he didn’t have a prior record of drug use and has since beaten addiction and turned his life around.

"It doesn't help the people of this state for Tyson not to have a car. He's got obligations to go to probation meetings, get to work, he's got to go to substance abuse counseling,” said Wesley Hottot during an interview in 2020. “All of those things are impossible in a place like Marion, Indiana without a car.”

In 2019, the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court which ruled the Constitution’s Excessive Fines clause doesn’t just apply to the federal government, but states, too.

Months later, a Grant County judge ruled the forfeiture did amount to an excessive fine – and Timbs got his Land Rover back.

But the case is back in court again. The Indiana Attorney General appealed that lower court ruling and the case is now before the Indiana Supreme Court.

“Incredibly, the State of Indiana has devoted nearly a decade to trying to confiscate a vehicle from a low-income recovering addict. No one should have to spend eight years fighting the government just to get back their car,” said Sam Gedge, Timbs’ attorney.

A spokesperson for the State of Indiana responded with a statement:

"The State of Indiana is appealing for two main reasons. First, prosecutors need greater clarity as to how the Indiana Supreme Court will apply the “grossly disproportionate” standard it set forth the last time it had the case before it. Second, if the Indiana Supreme Court decides that this forfeiture is “grossly disproportionate”—despite Tyson Timbs’ use of the vehicle to deal heroin and to buy over $30,000 of heroin—the State will need to decide whether to ask the U.S. Supreme Court to weigh in, as such a result could impact forfeitures not only in Indiana but across the country."

Here is the video from the 2020 story with Timbs:

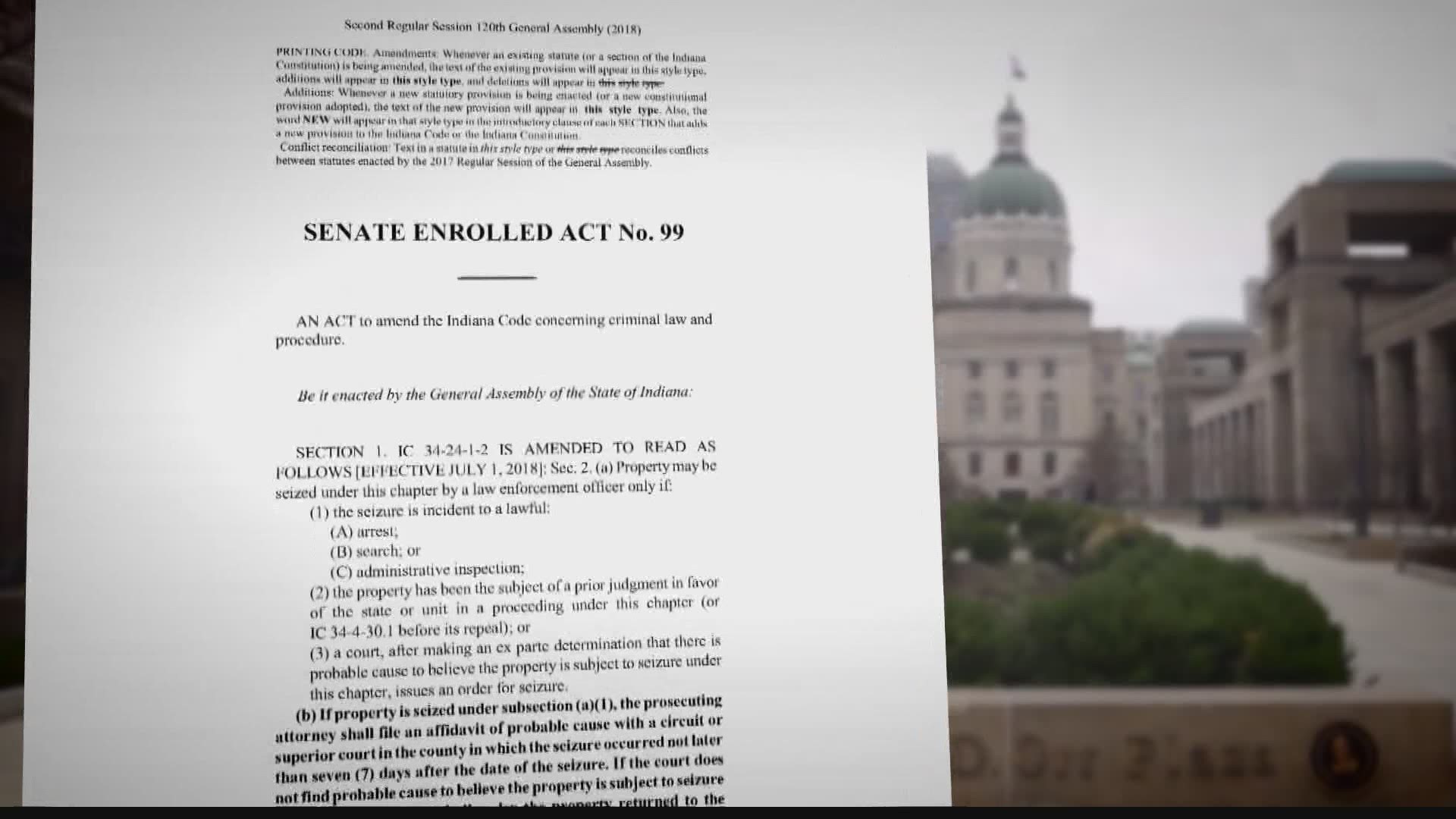

2018 reforms

In 2018, Indiana reformed its civil forfeiture law, requiring that prosecutors file probable cause within seven days of seizing a vehicle. If the court finds none, the car goes back to the owner.

It also allows owners who have vehicles or property taken – to file for a “provisional release” of the property as the forfeiture case moves through the court system.

Another reform shortens deadlines for prosecutors to file a forfeiture complaint.

Additionally, the law specified where exactly proceeds from civil forfeiture should go. Money should first be used to reimburse law enforcement agencies for the cost of investigating, then to police departments, and finally to the Indiana Common School Fund.

The Institute for Justice estimates 93 percent of revenues end up going to law enforcement.

More changes to come?

State Senator Phil Boots wants to go even further.

“The Constitution says there's a process that should be followed and often times we're not using that process,” he said.

Boots filed a bill in the 2021 legislature that would require people be criminally charged and convicted of a crime before their property can be seized.

Senate Bill 24 would also establish “procedures by which a property owner may regain custody of seized property pending a final determination of the forfeiture action.”

Jeana Horner says those are all steps in the right direction.

“I'm glad that somebody's picking up the torch and running with it,” she said. “Because its not right.”