How new technology at the US-Mexico border aims to stop fentanyl from coming across

Our team traveled to Laredo, Texas, where questions arise about whether enough is being done as we see a record number of overdoses.

On the U.S.-Mexico border sits the town of Laredo, Texas.

Ninety-five percent of the people who live there are Hispanic. A bulk of them are Catholic. The only thing that separates the town of 300,000 people from Mexico is the Rio Grande River.

“Nuestra is power. Our story is power,” said Mayor Pete Saenz as he walked the streets of downtown Laredo, highlighting the culture that can be seen around every corner.

Saenz was born and raised here. Many locals have never left.

“What makes Laredo so important, too, is we’re the number one land port. We are number one land port in the nation in terms of trade,” Saenz said.

They welcome the on-flow of trains, trucks, cars and even walkers heading over the bridge from Mexico.

“The river doesn’t divide us. It really connects us,” Saenz said. The Rio Grande is just 200 feet wide between Laredo and Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. It’s what makes this town unique.

“Laredo does 60% of Mexico's trade...40% trade with the U.S. and Mexico,” Saenz said.

But what isn’t unique is that this town of 300,000 people is battling the same problem as many other cities across the country.

“Our overdoses are up 100% from last year. Fentanyl is very real,” Saenz said. "It’s got to be stopped, and the key is the border.”

Keeping goods in, drugs out Some illicit substances have even been found in machinery parts, according to border control.

Fentanyl is making its way from China to Mexico and then moves across the border into the U.S.

That’s why 10 Investigates headed 8 miles north from downtown Laredo to the World Trade Bridge, where we met exclusively with border patrol officers.

“There are 10,000 trucks daily crossing from Laredo, Texas. The only thing separating us from Mexico is that bridge right there,” said Assistant Port Director Javier Vasquez with U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

The agency is in charge of overseeing and inspecting the shipments coming into the country.

“On a typical day, you’ll see the bridge half full. We are making sure U.S. consumers get their goods on time,” Vasquez said.

They are also working to keep narcotics, like fentanyl, out.

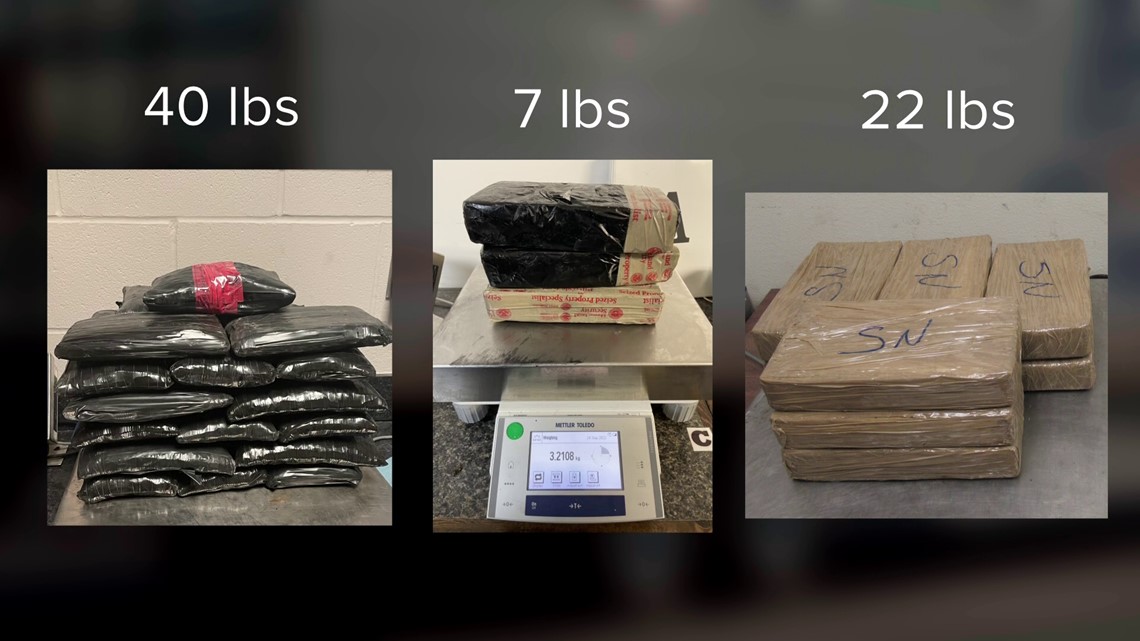

“We’ve seen all types of drugs here in Laredo. We’ve seen it in tires, in equipment itself, floors, ceilings, the commodity. Recently, we had one with broccoli and cabbage. We have meth hidden within the boxes. We’ve found drugs in machinery parts and automotive cabs,” Vasquez said.

In just the past few months, the Laredo Field Office area, which is comprised of eight ports of entry from Brownsville to Del Rio, seized enough fentanyl that could kill everyone in the state of Florida. The latest data obtained by 10 Investigates shows five times as much fentanyl has been seized by border patrol in 2022 than in 2019.

Innovative technology helps spot drugs There are just not enough resources to go around.

While there have been a record number of seizures, we are still seeing a record number of overdoses, so we asked if enough is being done to stop this drug from coming into our communities.

“I know CBP is investing a lot of money in technology, especially here at the World Trade Bridge,” Vasquez said.

The Assistant Port Director says the brand-new technology at the World Trade Bridge Port of Entry is a Multi-Energy Portal (MEP) system. The FORTUNE 500 company Leidos has a $480 million contract to integrate the systems at sites across the U.S.

After trucks drive through the first point of entry, the ones that are flagged are then sent to the second point, which is the MEP machine. It uses multi-energy technology, X-rays to check cargo similar to what’s used to screen baggage at airports.

“When the driver passes through the MEP, the low dosage of energy is on the driver. The high energy is on the trailer itself. We have shipments of machinery, so for steel items, we need something that can penetrate steel and look inside. This high-energy we can see what’s inside," Vasquez said.

There is a team of officers that monitor the cargo scans.

“They sit here and can take a look at what’s inside, so we don’t have to unload the trailers, which is time-consuming, and we have to find a balance where we don’t slow down the drivers and the trade coming in,” Vasquez said.

But the problem is there’s only one of these machines in Laredo. One other is in Brownsville, Texas. There are 50 crossings along the U.S.-Mexico border. That’s where officers are checking automotive parts, groceries and other items that are part of the trade economy.

At the World Trade Bridge port, where there’s one machine, there are 15 lanes truckers can drive through.

“Laredo is one of the test beds. The next phase is for us to have four additional machines at pre-primary area. We will eventually have 15 machines, so every single truck and everything is 100% scanned,” Vasquez said.

But that takes time. The next phase of the four machines could take more than a year to construct.

“We have to have that balance. The time it takes to install them, we have other officers out there, dogs, the old technology. The other tools we have go hand in hand,” Vasquez said.

He says they will never say no to more resources.

“The more people, the more technology we have will help us with the smuggling come across from the border,” Vasquez said.

Stopping the fentanyl epidemic "...It takes a full community effort."

Because once it makes it across the border, it can make its way to Tampa Bay in just 19 hours. Once fentanyl hits the streets, it takes the equivalent of less than five to seven grains of table salt to make someone overdose. A salt shaker’s worth of fentanyl could wipe out entire populations like Venice, Haines City or Tarpon Springs.

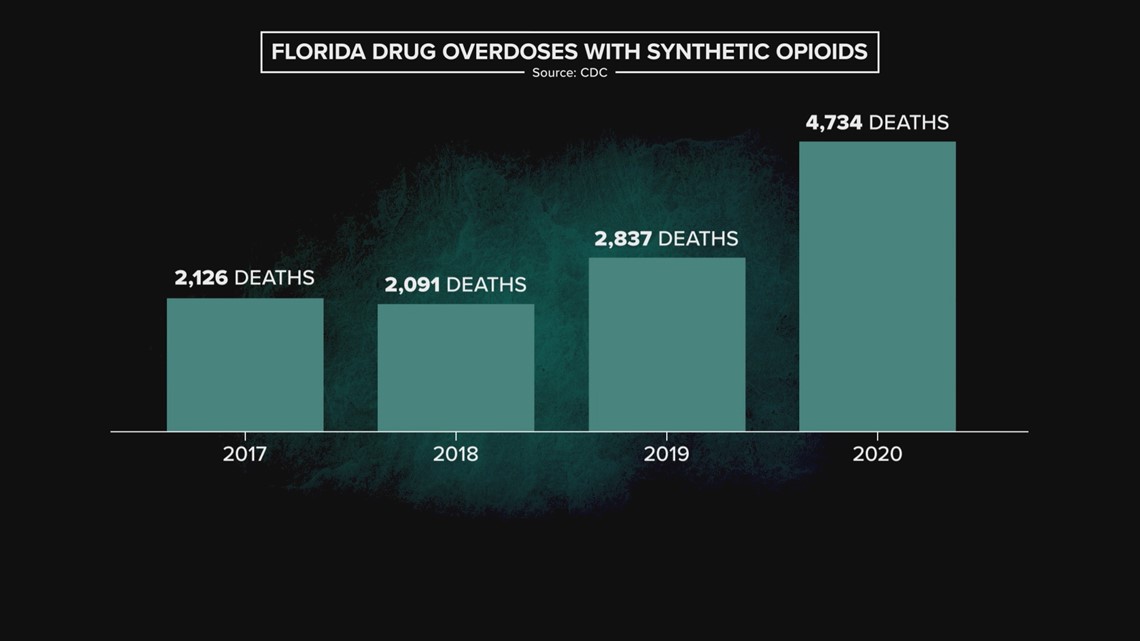

The number of drug overdoses in Florida involving synthetic opioids increased from 2,837 in 2019 to 4,734 in 2020, according to CDC data.

Here’s why experts say we are seeing more fentanyl coming into the U.S. from Mexico. Let’s start with a report from the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit public policy organization based in Washington, D.C., with more than 300 policy experts from all across the world.

Their researchers found prior to 2018, China was a direct supplier of fentanyl, shipping the finished product to the U.S.; however, China changed how it classified the drugs in 2019. That’s when the chemicals started going to Mexican cartels, and as a result, the drug is smuggled into the U.S.

According to the CDC, the U.S. is in a third wave of overdoses. The first wave of drugs included prescriptions in the 1990s. Then, it was heroin in the early 2000s, and starting in 2013, the next wave was synthetic opioids, like fentanyl.

Former DEA Acting Administrator Uttam Dhillon says Mexican drug cartels have what they need to produce the drug. He says these groups are the biggest threat to the U.S. and believes they should be considered terrorist organizations. He also says fentanyl should be considered a weapon of mass destruction and shared the same sentiments with Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody. Back in October, Polk County Sheriff Grady Judd blamed cartels for the agency’s largest fentanyl bust.

According to the DEA, the two main cartels responsible for fentanyl are the CJNG and the Sinaloa. Both are based in Mexico. Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman was once Sinaloa’s cartel leader. He made headlines in the U.S. when he was sentenced to life in prison for dozens of drug-related charges.

According to the public policy research organization Cato Institute, more than 86 percent of convicted drug traffickers in 2021 were U.S. citizens. The group looked at data from the U.S. Sentencing Commission on federal convictions. Cato researchers say they are subject to less scrutiny, so Americans are able to more easily smuggle drugs. Cato also found more than 90 percent of seizures occur at legal crossing points or checkpoints.

10 Investigates Reporter Jennifer Titus sat down with Mike Furgason, the DEA Assistant Special Agent in Charge at the Tampa District Office, to talk about how fentanyl comes from the border and into our community. He says there needs to be a multi-layered approach to stop the fentanyl epidemic:

“I think it takes a full community effort. DEA believes that our education programs, our enforcement and our communication with our state local counterparts and combining with state and local counterparts will be successful. But the most important thing we have to do is attack those organizations," Furgason said. "There are two organizations responsible for fentanyl coming into the United States. It’s CJNG and Sinaloa both based in Mexico, and they've been stalwarts of drug trafficking organizations for a very long time. And it's gonna take a full attack on those organizations, both domestically and internationally to dismantle them.”

In a 2020 intelligence report, the DEA said Mexican Transnational Criminal Organizations (TCOs) are diversifying their sources of supply. It shows the flow of fentanyl from China or India to Mexico or Canada where it’s being smuggled into the U.S.

Parents should be aware that a study published earlier this year in the JAMA shows three-quarters of teen overdose deaths last year involved fentanyl. That’s why Furgason recommends checking out the emoji decoder on the DEA’s website. It's part of the agency’s One Pill Can Kill campaign. In addition to how fentanyl gets to the streets in the Tampa Bay area, Furgason talked to 10 Investigates about rainbow fentanyl and what parents need to look out for with their kids.

You can see our extended interview on our streaming platforms, including 10 Tampa Bay+.

You can find addiction resources and learn more about the problem and possible solutions to the fentanyl epidemic in Florida through our series Overdosed.

10 Tampa Bay's Liz Crawford recently spoke with families impacted by fentanyl overdoses. You can watch their discussion in Faces of Fentanyl.