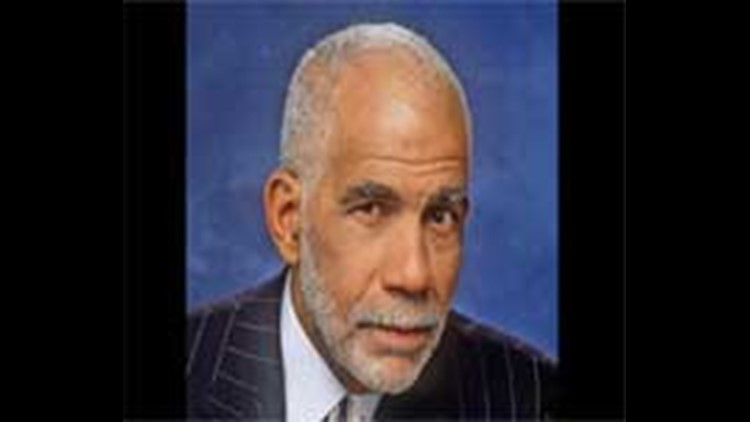

With his signature beard and earring, he more resembled the image of a musician than an award-winning journalist and 26-year veteran of "60 Minutes." But Bradley, who died Thursday of leukemia at 65, straddled many worlds during his career at CBS News.

He covered Vietnam and the White House. He profiled singer Lena Horne and scored the only TV interview with Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh. He collected the latest of his 19 Emmys for a segment on the reopening of the 50-year-old racial murder case of Emmett Till.

He defied expectations and stereotypes, and, as a black man who penetrated an overwhelmingly white profession, broke racial barriers along the way.

Bradley "was tough in an interview, he was insistent on getting an interview," said former CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite, "and at the same time when the interview was over, when the subject had taken a pretty heavy lashing by him, they left as friends. He was that kind of guy."

"He could do it all," said Mike Wallace, Bradley's longtime "60 Minutes" colleague. "When he was doing the story of the Vietnamese boat people in the 1970s, I'll never forget the picture of Ed picking up a man who was about to drown, and helping him avoid drowning by bringing him back to safety."

Though he had been ill and had undergone heart bypass surgery about a year ago, he remained active on "60 Minutes." In a segment airing last month, he scored the first interview with the Duke lacrosse players accused of rape.

Wallace said Bradley was "private" about his illness. "The first time I really understood that he was ill, on the air, was a couple of weeks ago. He was narrating a story, and his rich voice wasn't there anymore. It was just thinner."

Bradley's years on "60 Minutes" took him a long way from his start in broadcasting: as a schoolteacher moonlighting on a radio station in his native Philadelphia as a jazz DJ.

But he was always mindful of where he had come from, said journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault, a longtime friend.

"He was a star that never forgot his roots," she said. "He could do stories of every kind, and do it excellently. He never hesitated to do stories about his own people."

And, in recent years, he took on a side gig that recalled his professional beginnings: radio host for "Jazz at Lincoln Center," for which he won one of his four Peabody awards.

Wynton Marsalis, artistic director of Lincoln Center's jazz department, called Bradley "one of our definitive cultural figures, a man of unsurpassed curiosity, intelligence, dignity and heart."

Born June 22, 1941, Bradley grew up in a tough section of Philadelphia, where he once recalled that his parents worked 20-hour days at two jobs apiece. "I was told, 'You can be anything you want, kid,'" he once told an interviewer. "When you hear that often enough, you believe it."

After graduating from the historically black Cheyney State College (now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania), he launched his radio career as jazz DJ and news reporter in 1963. He moved to New York's WCBS radio four years later.

Then, in 1971, he moved to Paris and hung out, enjoying the art scene until his money ran out, whereupon he joined CBS News as a stringer in its Paris bureau. A year later, he transferred to the Saigon bureau during the Vietnam War, and was wounded while on assignment in Cambodia. He was named a CBS News correspondent in early 1973 and moved to the Washington bureau in June 1974. He later returned to Vietnam, covering the fall of that country and Cambodia.

After Southeast Asia, Bradley returned to the United States and covered Jimmy Carter's successful campaign for the White House. He followed Carter to Washington, in 1976 becoming CBS' first black White House correspondent, a prestigious position that Bradley didn't enjoy.

Seeking a longer form of storytelling, he jumped from Washington to doing pieces for "CBS Reports," traveling to Cambodia, China, Malaysia and Saudi Arabia. It was his Emmy-winning 1979 piece on Vietnamese boat refugees that eventually landed his work on "60 Minutes."

He joined "60 Minutes" in 1981 when Dan Rather left to replace Cronkite as anchor of "The CBS Evening News."

"60 Minutes" producer Don Hewitt, in his book "Minute by Minute," was quick to appreciate Bradley. "He's so good and so savvy and so lights up the tube every time he's on it that I wonder what took us so long," Hewitt wrote.

As an interviewer, "Ed could get people to say the damndest thing because he put them at ease," said former NBC News anchor Tom Brokaw. "It was like talking not to a reporter, but talking to an interested counselor of some kind. He had this wonderful way of stroking his beard and saying, 'Well, what do you mean by that?"

President Bush issued a statement hailing Bradley as "one of the most accomplished journalists of our time."

Perhaps only once did his subject get the best of him: In a perfectly staged joke, Muhummad Ali pretended to doze off in mid-interview, then swatted at Bradley in his "sleep." For one rare moment before Ali began laughing, Bradley lost his cool.

In 2003 alone, Bradley won three Emmys: for lifetime achievement, a report on brain cancer patients and a report about sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic Church.

Accepting a lifetime achievement award from the National Association of Black Journalists two years later, he remembered being present at some of the organization's first meetings in New York.

"I look around this room tonight and I can see how much our profession has changed and our numbers have grown," he said. "I also see it every day as I travel the country reporting stories for '60 Minutes.' All I have to do is turn on the TV and I can see the progress that has been made."

But, he added, "There are many more rivers to cross, and many more stories to cover and, I hope, a lot left in this lifetime."

Bradley is survived by his wife, Patricia Blanchet.

(Copyright 2006 Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.)