INDIANAPOLIS — By the time police found a young man’s body, rotting on a neglected plot of farmland off a Rensselaer highway in the fall of 1983, he had already been dead more than a year.

The man had been found by a hunter laying down traps for foxes. At first, authorities thought the skull might belong to a monkey. Closer, more official examinations found the bundle of skull, teeth, jawbones, femur, tennis shoe, and bits of reddish hair recovered from the scene proved to be the remains of a man between 18 and 26 years old whose life, police believed, was cut short by homicide.

Those remains would stay locked, though not necessarily unexamined, in the recesses of the Jasper County Coroner’s office evidence room for more than two decades.

By the time Andy Boersma took over that position in 2000, he had inherited the case of a young man whose identity had haunted three coroners before him.

The case remained unsolved, and Boersma was unsatisfied.

“I just wasn't about to leave this kid laying in a box in the evidence room, without trying to put forth some effort to locate his family and return his remains. Somebody out there is looking for their son, and somebody has to take the initiative," he said.

He reopened the case. For the next 20 years, Boersma would pour through evidence about it any chance he got. A thick binder containing case information was hauled into his truck on fishing trips. His spare time was spent poring through NAMUS, the National Resource Center for Missing and Unclaimed Persons records, hoping to find a match.

“Everything sat at a standstill. Other than what identifying markers we had, which was a crooked tooth and the jaw. A silver crown, or cap. That stuff was entered into the database that the state police and the FBI had, but none of the family had entered anything like that in his missing persons report,” Boersma said.

Without the resources of a full investigative unit on the case, giving the young John Doe his identity back was work Boersma and his wife, Diana, mostly took on alone.

Somewhere, he felt, a family whom he did not know was mourning the loss of this young man. He wanted to piece it together, and pestered any law enforcement agency that could help make an identification.

“Some of the state police officers, and some of the county sheriff's deputies, know that I'm a pain in the ass. And I don't let sleeping dogs lie. I got to kick the can every now and then,” Boersma said.

Then, at the start of 2021, Boersma got a call that would change the trajectory of his investigation.

It was from an intern who worked at a trans-led, forensic genealogy non-profit based in Massachusetts called The Trans Doe Task Force.

They specialize in finding and researching cases of LGBTQ+ missing and murdered people to make positive identifications and were interested in assisting with the Jasper County John Doe case.

It was work they had been doing for years as part of the DNA Doe Project, before branching off to create a unit dedicated to identifying missing people in the LGBTQ+ community, with a specific focus on victims who may have been trans.

“While we were working with them doing genealogy, we asked each other, could we find trans cases? Could we be able to help out our own community through this work that we're already doing? And we thought maybe we would find a couple cases. And now we've found about 175,” said Anthony Redgrave, a forensic genealogist who helped found the non-profit in 2018.

Their team leverages the science of genealogy to solve decades old cases, using family genetics to piece together mysteries.

It’s the same technology that was used to identify the Golden State Killer and, locally, what Indiana detectives used to identify the so-called 'I-65 Killer' as Harry Edward Greenwell.

“Instead of having the information from an adoptee of their birth date, and roughly where they were born, what we have instead is information from anthropologists that gives us a post-mortem interval and age estimate, which gives us a broad range of how old the person might be,” Redgrave said.

The organization assists law enforcement departments, medical examiners or forensic anthropologists with getting their cases worked on by forensic genetic genealogists.

“Really cannot overstate the importance of the grassroots work that they do. They are like complete workhorses. And they actually get things done,” said Dr. Amy Michael, a biological anthropologist out of New Hampshire who assists the task force.

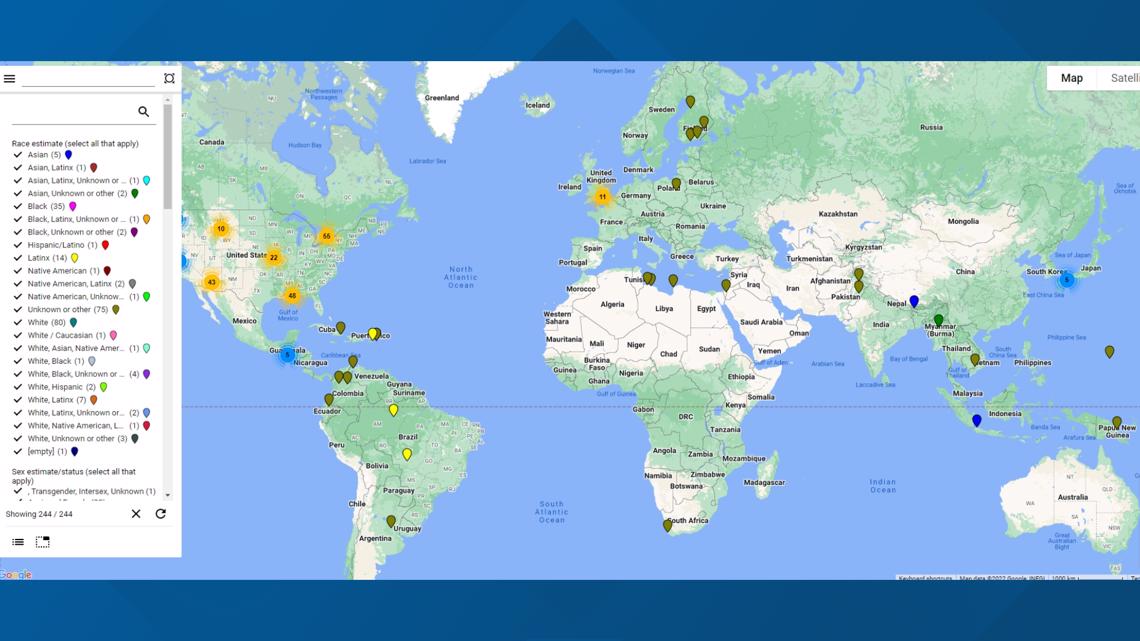

Their team also established a LAAMP database, a free service which allows people to submit case information about missing people who may have been LGBTQ+, or whose case requires LGBTQ+ informed care and consideration. An additional TDTF Map on their site shows information about cases currently being investigated.

From the start, the Jasper County John Doe was a speck on that map. Although they couldn't know for sure whether the young man belonged to the LGBTQ+ community, there was one brutal fact about the case that motivated the Trans Doe Task Force to take it on.

While the Jasper County John Doe's identity remained a mystery, his killer's was well known.

The many crimes of Larry Eyler

Between 1982 and 1984, serial killer Larry Eyler terrorized large swaths of the Midwest.

"He was dubbed as the Highway Killer. And he would pick up transient people, or people who were hitchhiking. He would drug them and offer to do other things. And then, he would murder them," Boersma said.

In 1994, Eyler was dying in prison ahead of a scheduled execution for the death of a 15-year-old boy. He made a deathbed confession to then-lawyer Katherine Zellner, revealing a list of at least 20 men he killed over the years.

Most of those victims were part of the LGBTQ+ community. It was this horrific tendency of preying on gay men, almost exclusively, that was enough to motivate the Trans Doe Task Force to help solve the Jasper County John Doe case.

“We'd been aware of Larry Eyler and his unidentified victims for a long time, and we'd been wondering, why haven't these been worked on?” Redgrave said.

Eyler admitted to picking up a young man in 1982, along U.S. 41 near Vincennes, in southwestern Indiana. He admitted to killing him, then dumping his body about 70 miles south of Chicago.

Whether Eyler actually knew the Jasper County John Doe’s identity or not remains a mystery.

“He was going to take that one to his grave,” Boersma said.

If the young man had indeed been a member of the LGBTQ+ community in life, he would have been murdered during a time when queer people were not always accepted by the broader community, or even their own families.

Ted Fleischaker was the editor-in-chief at The Word Magazine, one of Indy’s only LGBTQ+ magazines in the early 80s. It was a time when multiple young men from the queer community went missing and then turned up murdered. That was sometimes at the hands of Larry Eyler, whose total victim count in Indiana remains uncertain.

Fleischaker recalled the societal prejudice and stigma of the time created an environment where young men could be targeted, but were left without a community to help.

“People preyed on the fact that a lot of these people had nobody at home, looking to see where they were. And if they disappeared, it would be weeks and weeks or longer before anybody would say they were missing," Fleischaker said.

The Trans Doe Task Force knows when they take on cases of homicide victims in the LGBTQ+ community, they may be the only ones looking for them.

“With regular John or Jane Doe case, you can say to yourself, oh, this person might have family who's looking for them. With LGBTQ cases, you don't have that guarantee, because sometimes people specifically have left because their family didn't support that. And the people who are going to be looking for them are the people who have no rights,” said Lee Redgrave, a co-founder of the Trans Doe Task Force.

The same year they took up the Jasper County John Doe case, the Human Rights Campaign group revealed there had been a record 57 known murders of transgender people – the most since 2013.

Despite the continued prevalence of violence against trans and queer people in the United States, the Trans Doe Task Force remains one of the only agencies that can apply a queer lens to cases that need them.

“As members of the community, we're pretty much constantly aware of the fact that we're not that far removed from being in that position. We could, at any turn in our life, have ended up in that same place. Because that's what the world has done to us,” Redgrave said.

Task force members take great care to ensure mistakes made by other law enforcement or investigative agencies, deadnaming or misgendering victims that can cause further harm to that person, does not happen.

"As the experts having lived in these bodies, and having to deal with this kind of level of violence and bias towards our people, need to be the one spearheading these initiatives. No one knows this content like we do, no matter how well meaning they are or experienced they are in related fields," Anthony said.

They would take the same care with the case of the young man found in Rensselaer.

His name is William Lewis

In January of 2021, Boersma accepted the task force's help in identification of the Jasper County John Doe.

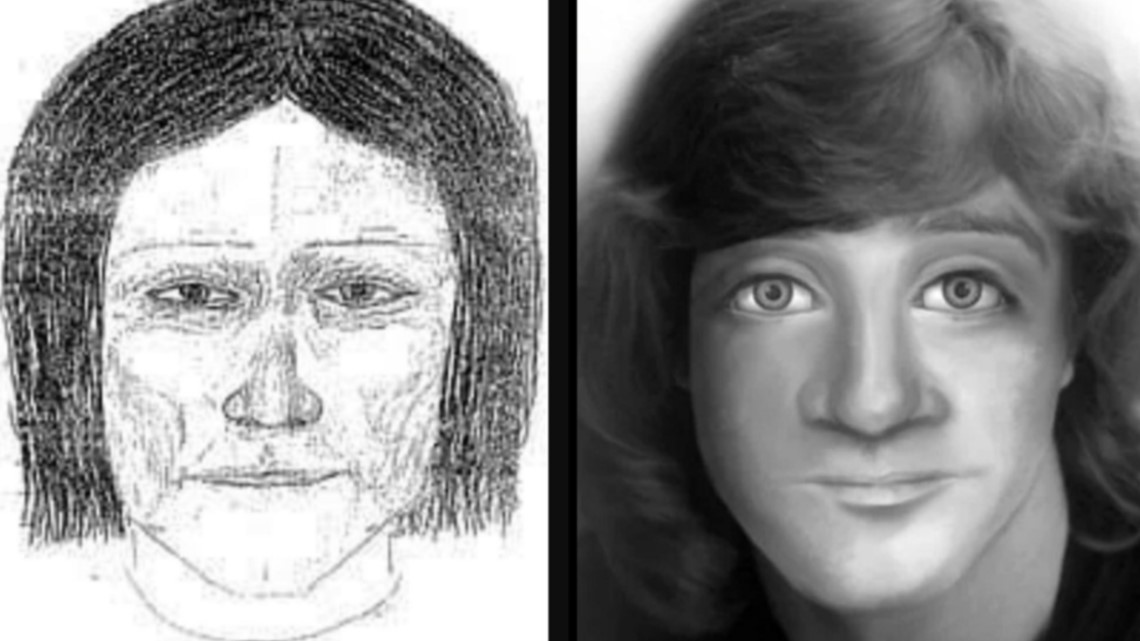

While awaiting DNA data, Anthony Redgrave was provided photos of the victim’s skeletal remains to produce a second piece of forensic art that could help lead to an identification.

From January to September of 2021, the victim’s DNA was processed and uploaded to GEDmatch, a free DNA site built for genetic genealogy research.

In just six days, that team of forensic genetic genealogists and student interns found a potential candidate.

Under the direction of Boersma, and an accompaniment of police, team member Katie Thomas was granted permission to make contact with the candidate’s family in order to obtain a DNA sample and gather further information.

"We were involved in a more unusual way. In finishing out a case, we aren't usually there. So, that was a very emotional experience for the team," Lee said.

The DNA sample, collected from a full sibling of the candidate, was compared to that of the Jasper County John Doe. It confirmed the two were siblings.

The Jasper County John Doe finally had a name.

A few days before Thanksgiving, Andy Boersma and the Trans Doe Task Force announced publicly that, after so many years, the young man found nearly forty years ago had been identified.

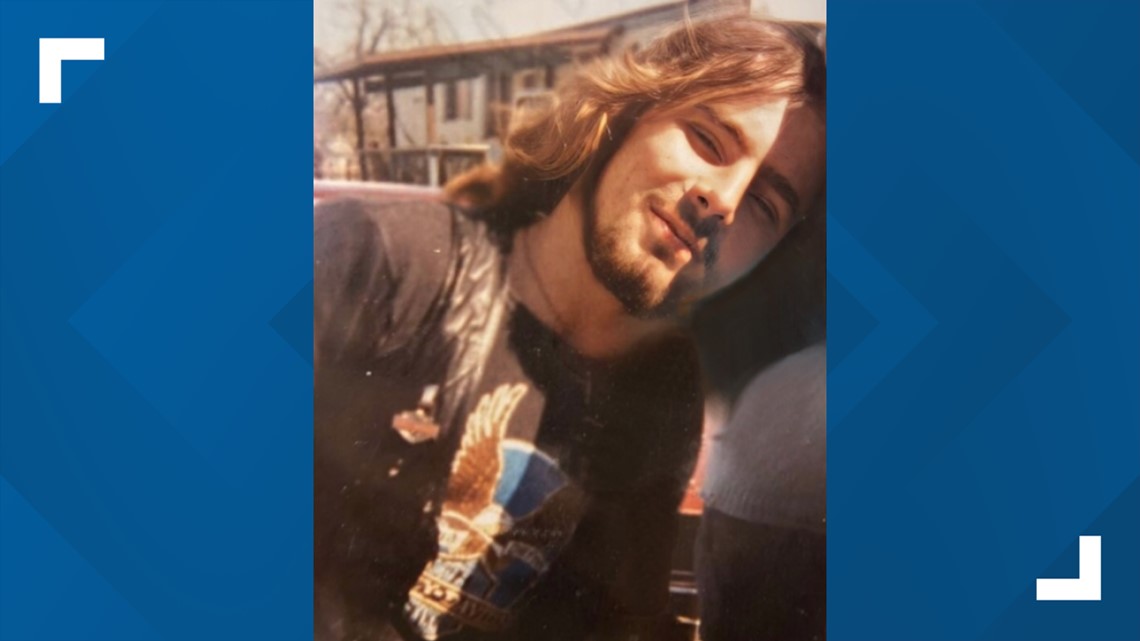

His name was William "Bill" Lewis. In life, he was a quiet person who played football in high school. Lewis was last seen by relatives in Houston, Texas in February of 1982. The 19-year-old attended a friend’s funeral in Indiana, and never made it back home.

He would be 58 years old, if he were still alive today.

For Andy Boersma and members with the Trans Doe Task Force who worked to make the identification, the announcement was not a time for celebration or to applaud themselves for years of hard work coming to an end.

When cases are closed, a somber reality is reiterated.

There are families like Lewis', who prayed he would one day come home, but now know he won't, across the country.

His parents did not live long enough to learn what happened to their son.

“He was loved a great deal. His parents looked for him until they passed. And then, his siblings had picked up from where the parents left off,” Lee said.

As far as they could tell, Lewis was not a part of the LGBTQ+ community. He was a young man caught in the wrong place, at the wrong time, and whose life ended on the side of the road by hands police had tried to track before.

For the Trans Doe Task Force though, it does not matter if a missing or murdered person was actually part of the LGBTQ+ community or not.

As cases continue pouring in from across the country and their work expands to countries like Canada, Argentina, Finland or Libya, they refuse to let these victims who may have been forgotten in life remain so in death.

"There's this concept of chosen family, of who is taking care of these cases. If they won't look for you," Lee said. "I definitely feel like we adopt people until we can find out where they go."

If you want to learn more about the Task Force, or learn how to get information into their LAAMP database, head to this link.