LAKE COUNTY, INDIANA, Ind. — On the news, we often share sketches of criminals, kidnappers and killers who police are desperately trying to catch.

But what goes into creating those drawings?

Exactly how does a police sketch artist help witnesses fight crime?

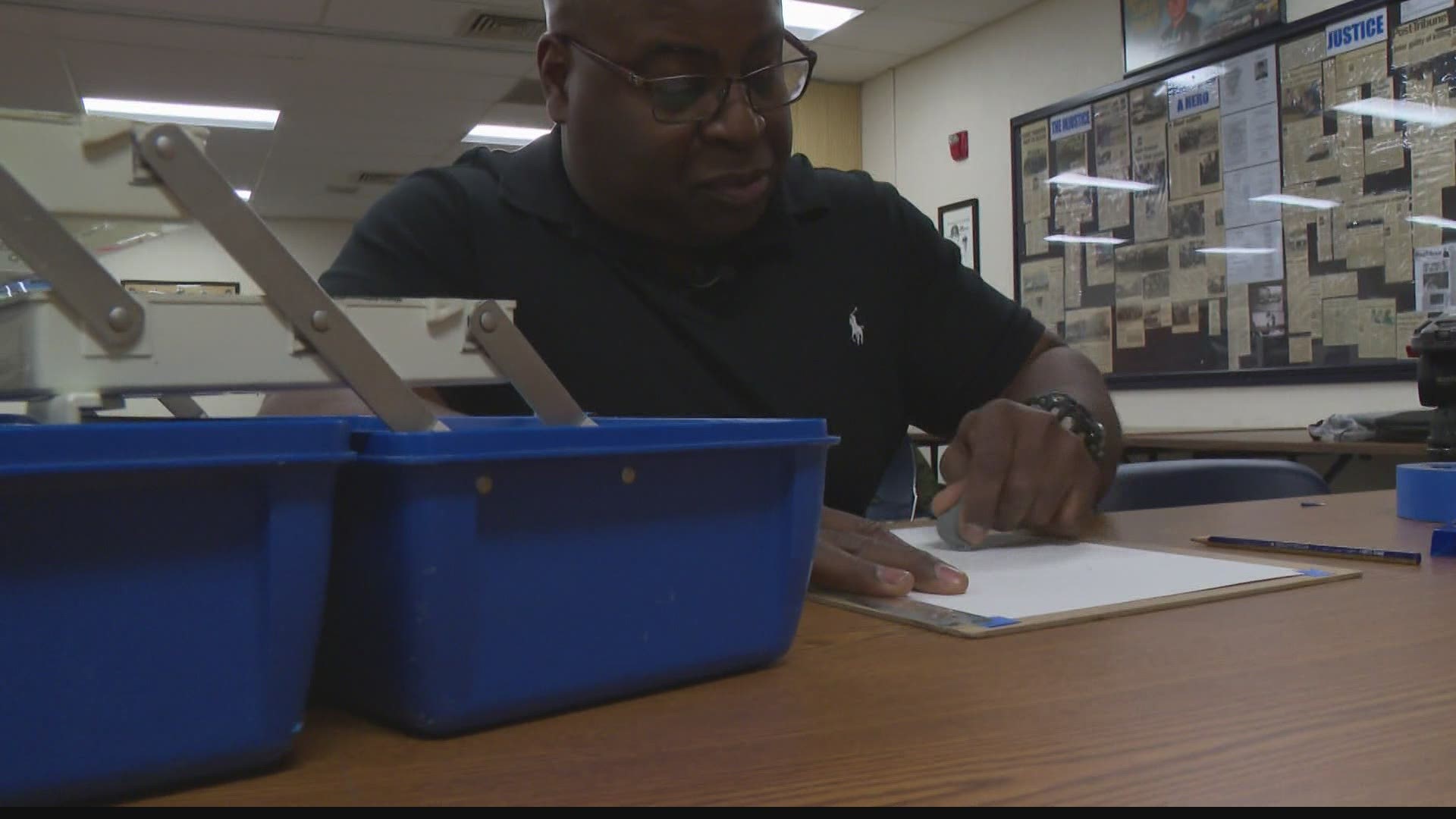

For Trooper Taylor Bryant, with Indiana State Police, it's a calling and a fulfilling part of the job serving the public.

Why he does it

Picture a face from memory.

Now, imagine you only saw that person for a few moments during a crime.

Could you describe them?

Provide a portrait that other people recognize?

Well, with each pencil stroke, Bryant has to bring those crucial memories from victims and witnesses to life.

"You want to be a help on every drawing you do because, you know, you have people who have been wronged by this individual and you want to get some kind of satisfaction in this case," Bryant said. "You want activity, people calling in because possibly one of those tips or call-ins can lead to an apprehension."

Sketching criminals isn't his day job.

Most of Bryant's time is spent patrolling the highway, as a commercial vehicle enforcement officer at the Lowell post.

But Bryant also has done about 70 sketches for police departments across the state.

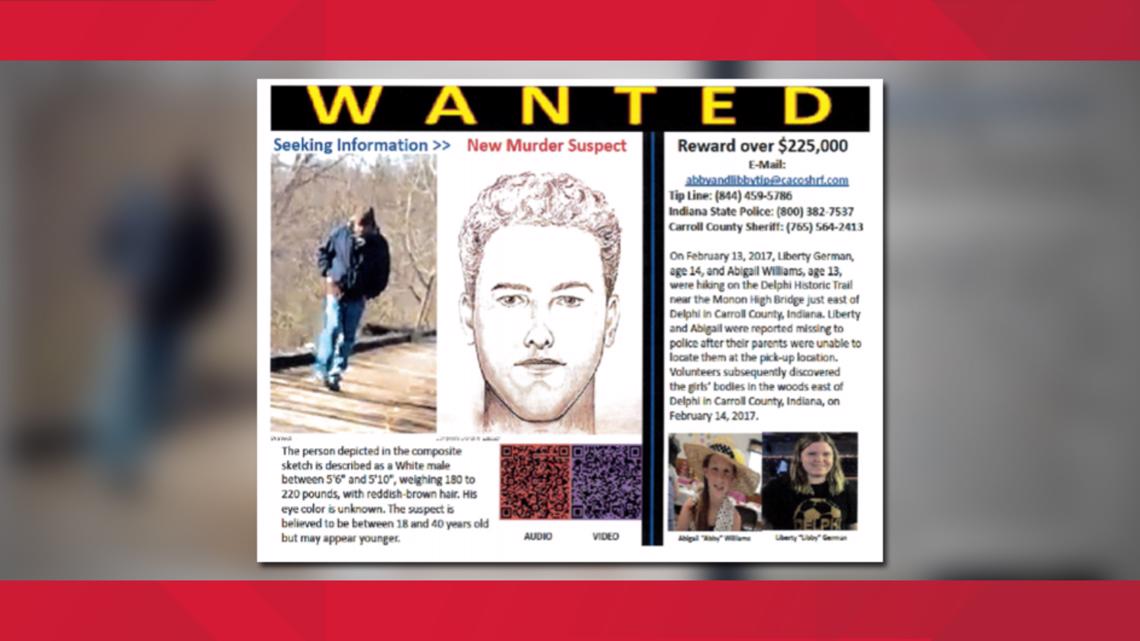

That includes a high-profile picture we've seen a lot: the man police believe killed Abby Williams and Libby German in Delphi.

He's not allowed to talk about it since the investigation is still active.

But make no mistake — this is a sketch he really hopes leads to an arrest.

"It was a sketch created from a witness. That's about all I can say," Bryant said. "Yes, I believe the whole country really would like to see something come of this."

How he started

Bryant started sketching suspects in 2008.

That's when State Police put out a memo saying they were looking for a trooper with artistic ability.

Bryant has a degree in commercial art from the University of Evansville.

So he accepted the challenge and trained for three weeks with the FBI in Virginia.

"We learned how to interview witnesses, how to talk to a witness, how to not ask leading questions of a witness," he said.

He also learned the most important part of the job happens well before pencil ever hits paper.

This is a four-hour process that starts with an interview.

It takes time.

It's often filled with tears and emotion.

Bryant wears plainclothes, not his uniform, to make the victim and/or witness feel more comfortable.

"Sometimes it's a harrowing experience for the witness. You know, sexual assaults, things of that nature, so you want to get them to more or less trust you to do a drawing," Bryant said.

Then, victims go through an FBI catalog, pointing at and choosing facial features that most match the suspect's look.

They pick out head shape, eye shape, nose and hair, for example.

Only then will Bryant finally start to sketch.

"I tell the witness 'I'm your artist. If something is going on, speak to me,'" Bryant said. "I'm periodically checking with them and seeing is everything still looking as you like or whatever. 'Would you change anything? Move anything?'"

He's awaiting that light bulb moment in the end, when recognition sets in.

"Getting a response of 'oh.. wow...yeah. You know, that's the guy,'" he said.

When the drawing goes public, the goal is to generate tips and get an arrest.

That's happened a lot for Bryant.

And some cases in particular, stick with him.

Getting justice

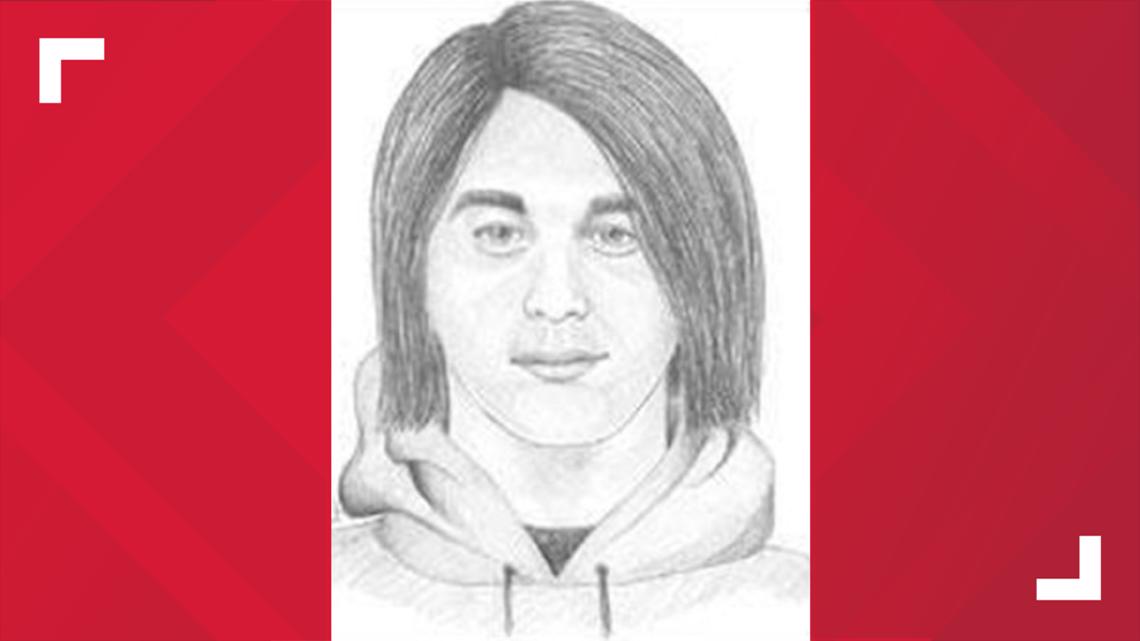

Two teenage brothers got arrested and convicted after the sketch he did with 77-year-old Mary Voland.

"Yes, yes, and that was maybe my second sketch," Bryant said, recalling his work after a deadly attack in Brown County in 2008.

Stabbed and badly hurt, she watched her husband, Richard, get shot and killed in their own home.

"I remember doing the sketch at the hospital. I mean this was the week she was recovering from her injury and I had to listen to her story," Bryant said, "and she was a very, very good witness - described his olive skin - very good witness."

He said the main suspect, then 17-year-old Bennie Reed, cut his hair after the crime.

But people still recognized him and called in tips.

Within two months of that sketch's release came the arrest.

"I was very, very happy with the process of how it turned out," Bryant said.

The growing use of surveillance cameras has cut down on the need for composite sketches.

But when there's no video, DNA or fingerprints — a hand-drawn sketch, using this trooper's skill can give victims back their power and bring bad guys to justice.