INDIANAPOLIS — Harvest for farmers in Indiana normally only comes once a year.

But on one vacant urban lot on the east side of Indianapolis, two 40 foot shipping containers are filled to the brim with the freshest kale, mustard greens, and microgreens.

Inside this space, the food urban farmer DeMario Vitalis is growing at New Age Provisions can sustain a whole community, year-round. It's all possible through the process of hydroponics, a farming system that delivers water directly to the root of a plant.

Vitalis is the first farmer in Indiana to leverage the science of hydroponics inside shipping containers, and yields about five acres of food every year.

“Hydroponics open up a whole world of opportunities versus traditional farming. Because, with hydroponics, you can farm inside of a room, you can farm inside of a warehouse. You can farm on a table with the little arrow garden, or like I do, from inside a shipping container. So it's very versatile,” Vitalis said.

Vitalis is one of many farmers in Indianapolis whose fresh produce is being grown and distributed in spaces that are traditionally considered food deserts. In the middle of a state which last year ranked tenth in total agricultural food production, 200,000 people live in food deserts.

The city of Indianapolis has consistently ranked across multiple studies as one of the worst food deserts in the country. One study from 2018 showed at least 20 percent of Indianapolis residents live inside food deserts, areas where the nearest grocery store is more than a mile away, according to the USDA.

That’s a number that disproportionately affects Black people in Indianapolis, who represent a third of people living food deserts, despite not making up 30% of the population of Indianapolis. Meanwhile, just 18% of white people live in Indianapolis food deserts, even though they make up 60% of the population.

However, within these spaces where access to nutritious food can be hard to come by, it is Black gardeners and growers like Vitalis who are producing some of the freshest food in the city. The hydroponic process implemented within the shipping containers ensures the greens are pesticide-free and not vulnerable to bugs.

"You have to have healthy food in order to have a good sense of well-being, and a good overall life. If you don't have access to fresh foods, and you don't have access to nutritional food like this, then what are you going to do? You're going to go to the closest McDonald's. You're going to go to the closest chicken store or Jay Jays," Vitalis said.

Through a mix of innovative technology and community solutions, Black gardeners are bringing essential produce - and knowledge of how to grow it - to the next generation.

Dr. Jarrod Dortch is the owner of Solful Gardens in Indianapolis, an Indiana State Department of Agriculture recognized natural food provider. Their mission is to make fresh, natural food available to folks living in areas that may not easily get them, and leverage the power of community to disrupt industrialized food networks.

“With the ever-changing dynamics of grocery stores, it's more important now than ever to be able to sustain ourselves and to be economically stable as well," Dortch said.

According to InContext, an Indiana Business Research Center at Indiana University's Kelley School of Business publication, nearly two-thirds of Indiana’s 23 million acres is farmland. Marion County is among just a handful of Hoosier counties where just 11.4% of its land is farmland.

While Dortch said there has been an increase in Black-led organizations working to begin their own community gardens over the last five years, that already scant 11% is growing smaller.

"There's been an influx of larger farming groups that have taken quite a bit of the community's assets away from other smaller farmers by buying up the land," Dortch said.

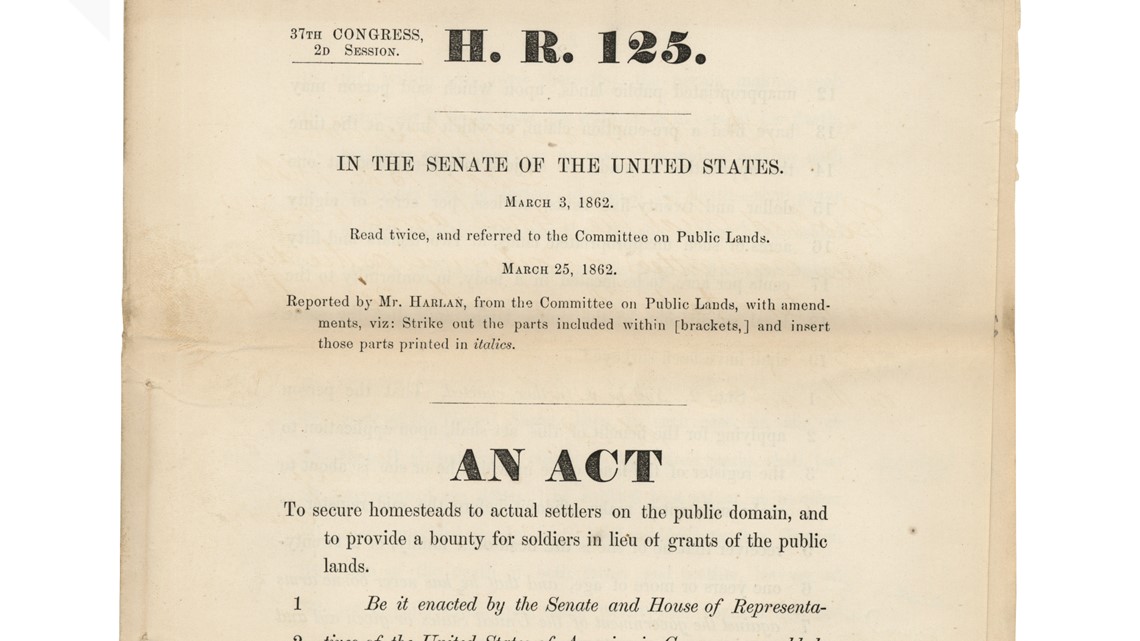

Lack of access to land for Black farmers, gardeners, or growers to cultivate food has historical and political roots. For centuries, the United States government worked systematically to separate Black people from land where they could have made a living farming. As early as 1860, the federal government passed The Homestead Act into law, which promised 160 acres of land for anyone willing to farm it. Black farmers were not eligible for those acres until 1866 because slavery was still legal until 1865.

Dr. Valerie Grim is a professor of African-American and Diaspora Studies at Indiana University, and said during the periods where Black families were burdened by racist policy making it difficult - or impossible - to profit from farmland, white families were turning massive profits and passing it onto their children.

“It's important to process what the federal government did in terms of making it possible for a white family to own land, and to become individual family farmers. This was also a way to transfer wealth from the federal government to families. They just did not do the same for Black families,” Grim said.

Presented barriers to large-scale farming productions, Black families would utilize whatever space available to feed their families and the larger communities. That often meant turning to the space in their own backyard, and sharing it with the greater community.

"A lot of Black people made up that difference in those deserts that way. From yard to yard, you could see gardens and people sharing things across gardens," Grim said.

But more racist policies preventing Black families from owning farms would affect their ability to garden in yards, which were difficult to obtain without owning a home. As America’s economy buckled under the Great Depression in the 1930s, the federal government faced a severe housing shortage crisis. In an effort to stave off what seemed like an inevitable wave of foreclosures on American houses, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the National Housing Act into law in the summer of 1934.

That legislation created the Federal Housing Administration, which was the first entity to implement redlining practices. Government surveyors graded homes on a scale from A to D - A was most desirable, D was least.

According to the government, property values in areas marked “D” and red were likely to go down. People who lived there were subsequently considered unworthy of homeownership or lending programs.

A majority of the areas given a “D” rating were neighborhoods where Black people lived. Merely existing as a Black homeowner within a space was cause for the surveyors to give the area a D rating, and families were further denied loans.

Researcher Brian Healey studied the effects of redlining on current food deserts for an IU-based project called Foodways Project, in 2021, and found a direct correlation between areas of the city that were given a 'D' rating, or the most undesirable rating decades ago, and current food deserts.

"As all of this redlining went on, they were denied loans and couldn't improve their neighborhoods. Then, stores did not want to move into these neighborhoods. So then, there was a lack of food stores, hardware stores, anything that they can use. People had to travel long distances to even access things like food, like goods, food especially. That continues today," Healey said.

The impacts of redlining, and its continued influence on areas struggling with access to fresh and affordable food, are real.

But to reduce these areas of Indianapolis to nothing but abandoned swaths of dirt where nothing ever grows is to ignore the persistent work of Black farmers and gardeners who remain committed to providing fresh produce to communities suffering from decades of racist policy, and who leverage the power of community to so.

"I have a community garden that's free and available to all my neighbors. And, besides that, we've done some trainings to schools and the individuals and families about how to grow vegetables," Dortch said

Community remains at the heart of both Solful Gardens and New Age Provisions, even in the midst of hardships that can accompany the task of working to grow food in areas not known for that practice, and on land not large enough to support full-scale food production.

When Vitalis went to the USDA in 2019 to get a loan for the shipping containers he now farms in, his request was initially denied.

"I think they took me for granted. You know, I came in there and they initially saw an African-American from the city. And then they're like, 'OK, well, what kind of farm and you're going to do?" Vitalis said.

But Vitalis remembered growing up hearing stories his grandparents told, about different recipes they cooked from greens tended by hand in southern Mississippi soil.

"During that time, you know, it wasn't too encouraging for Black folks and people of color, but we maintain. And we do what we can do. They were raised on the farm that they were once slaves on. And then, once my grandmother became of age, she went off. She was able to go to school, get an education, and when she became a teenager, she got up out the South," Vitalis said.

If his grandparents could find ways to farm land in their community, so would he. Vitalis appealed the decision, and a judge eventually sided with him. By 2020, his shipping container business was up and running.

"It's huge for me to have an opportunity to share my knowledge with people who don't have the opportunity to be exposed to it. To show people who look like me that there's opportunities outside of traditional farming," he said.

As he works to offer fresh produce to the community, that is a lesson he wants to pass on to the next generation.

"This is a type of farming that I want people to become aware of. Because if they're like me and just don't have the access to land, don't have the knowledge behind traditional farming to do that, this is maybe a turnkey solution that you can look into that can maybe overcome," Vitalis said.