INDIANAPOLIS — (WTHR) — For the older generation, it was Rodney King.

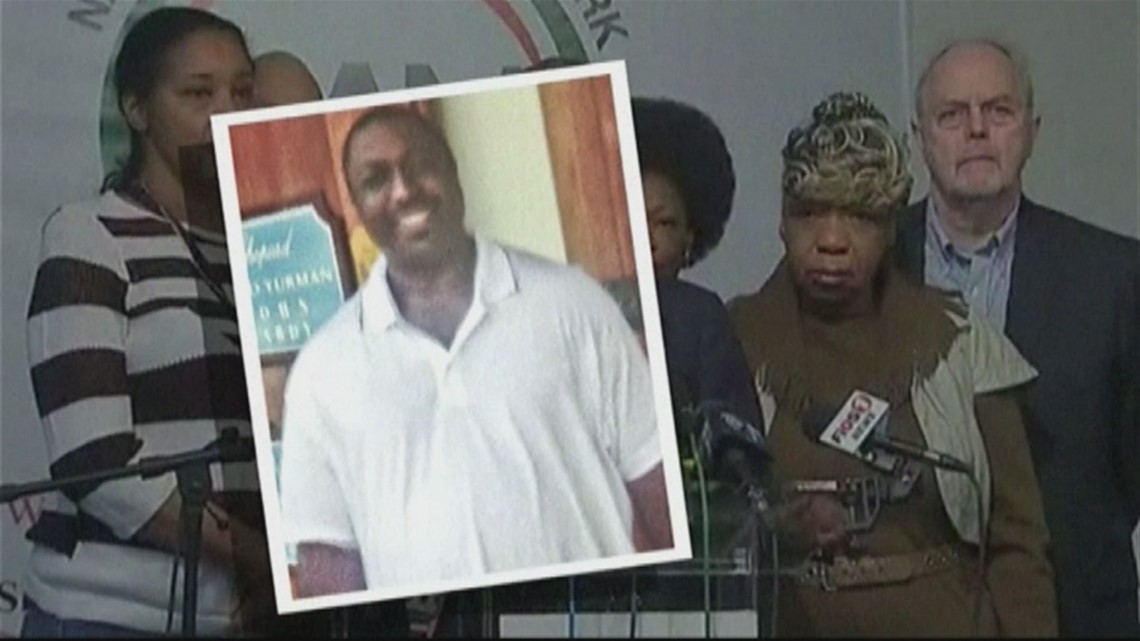

For younger millennials and Gen Z-ers, it was Freddie Gray, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Breonna Taylor, so many others, and most recently George Floyd.

The viral video filmed by 17-year-old Darnella Frazier in Minneapolis of officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on the neck Floyd for eight minutes and 46 seconds as other officers stood by, erupted into protests across the country and around the world. Demonstrators of all races began calling for change to the systemic issues, which allow the list of previously mentioned names to continue to grow and often with impunity.

Indianapolis mom Debricka Frazier said as a mother she can’t help but worry about her children.

“I mean, I ask him does he really understand what it’s like being black," she said. "I’m like ‘do you realize you’re a Black, deaf, male and you’re out in the world, anything can happen to you? It doesn’t seem like he’s really concerned, or that it’s sunk in him yet, but I need it to really sink in."

Frazier said she has been pulled over for speeding tickets in the past but has only interacted with officers who were doing their job and upholding the law in an effort to serve and protect.

Her 19-year-old son D.J. Goodner said having grown up with these viral videos of police violence, he thinks what happened to Floyd and countless others “is not right."

"Things need to be fair and we need to be treated equally now," he said. “It’s getting worse and worse every day. It’s frustrating for us people of color not just in the United States but around the world."

But justice advocates in the U.S. said that as the world begins to discuss police use of force, police violence and justice reform there’s a major piece of the dialogue that is missing.

“Most of the people whose stories we’ve heard about on television, or who unfortunately we’ve seen a lot of violent, catastrophic encounters with law enforcement the vast majority of them are in fact disabled,” said Community Lawyer and Helping Educate to Advance the Rights of Deaf Communities (HEARD) Volunteer Director Talila Lewis.

Eric Garner and Laquan McDonald had disabilities

“Freddie Gray was a survivor of lead poisoning, Eric Garner had asthma, Laquan McDonald had multiple disabilities including complex PTSD. The vast majority of people who we are witnessing their deaths at the hands of law enforcement do in fact have disabilities,” said Lewis.

In a legal context, disability is defined by the American Disabilities Act (ADA) as a “physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of major life activities, a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment. The ADA does not specifically name all of the impairments that are covered.”

But oversimplification by advocates, the media and others plays a role in changing the narrative of these stories.

“What we’re finding is that news media, advocates and families alike for various reasons erase parts of those identities," Lewis said. "So within racial and economic justice advocacy spaces they tend to erase disability identities and within disability and deaf advocacy spaces they tend to erase race, class and other marginalized identities like gender, sexual orientation, former incarcerated status and things of that nature that really do play a role in these catastrophic encounters with law enforcement."

33 to 50 percent of all use-of-force incident involve a person who is disabled

Law enforcement is not required to keep data on use of force, police killings or violence. Justice advocates say the lack of data is part of the problem.

“The statistics that we have are based on public records act requests and media reports,” said ACLU Director of Disability Rights Program Susan Mizner. And based on the data collected a third to half of all use of force incidents involve a disabled person according to a study by the Ruderman Family Foundation.

Lewis argues that the number is probably a low estimate “because the methodology to define disability was very American Disability Act specific,” and required that people had been diagnosed.

“Whereas what we know is that most of the folks who are targeted by law enforcement don’t have those diagnoses prior to those interactions with law enforcement,” Lewis said.

Does training in recognizing disabilities or de-escalation help?

Lewis said part of the reason violence arises when it isn’t necessary is because there’s a one size fits all solution for a demographic that doesn’t conform to that notion.

“The simple act of handcuffing a deaf person is an act of violence. If a deaf person uses their hands to communicate. That in itself is violence,” said Lewis.

“Some people have disabilities that make it impossible to respond, some people are wearing headphones, so they can’t respond there’s myriad reasons why people might respond in the particularized way,” said Lewis.

Mizner said miscommunication between a person who police are not trained to recognize as disabled can lead to escalation.

“Often, it’s criminalization of survival, criminalization of existence as someone who is outside of those norms that is causing law enforcement to interact with these folks," Lewis said. "And that’s really what at the heart of all of these catastrophic encounters."

Mizner said “having police involved in situations that don’t really demand someone with a gun is all part of the mix.”

Lewis doesn't believe that more training is the answer and believes that “it’s often those who are trained who are enacting some of the worst violence against communities and that’s because they then are called upon more often to interact within(in) those communities."

Lewis said the Atlanta police officer who shot Rayshard Brooks in the back after he grabbed an officer’s taser and began to flee had recently been trained in descalation tactics. THV11 also reports that Garrett Rolfe had also taken cultural awareness coursework in April, and in January passed a course titled “Use of Deadly Force.”

There is plenty of anecdotal qualitative data to support de-escalation based training. And the Washington Post reports that in Baltimore “where training was overhauled” after a Justice Department investigation, “the police department saw excessive force complaints drop by 36 percent in 2016 and a further 42 percent in 2017.”

But without uniform data collection it is very difficult to quantify the impact of training on a national scale. Researchers from Harvard and Northeastern University found that police officer shootings (legal) recorded by the FBI and CDC are under counted.

Researchers have long been calling for peer reviewed evidence on use of force as it relates to the safety for both law enforcement and suspects.

Police officers are often called for situations that don’t necessarily fit into the box of crime fighting. It’s one of the reasons some police departments have started adding a social worker to their department. Last year, when Channel 13 profiled Bloomington’s Police Social Worker, Police Chief Mike Diekhoff said substance abuse, homelessness and mental health are generally repeat calls, so he created a force to respond to those calls, and police try their best, but they’re not social workers. So he added Melissa Stone to the department as one of Indiana’s first police social workers.

IMPD does not receive disability training but all officers are trained in crisis intervention.

“They’re trained in how to intervene and deescalate in situations where someone may need a little extra conversation, a little extra understanding,” said Sgt. Grace Sibley of IMPD. “We are also constantly seeking out better ways to listen to the community and to get feedback on the community on how to better serve or residents who may have other needs."

Frazier said in the few times she has been pulled, officers were doing their job as they should.

“Very calm, relaxed, always tell them I deaf, I get my pen and paper to write,” said Frazier. “People always say it should be their responsibility to get a paper and pen but it’s not a big deal to me. They’re usually fine with me and I’m fine with them."

Goodner hasn’t been pulled over or had any interaction with police other than saying hello. He said that if he were to be pulled over he would not reach for the pen and paper he needs to communicate until after he was certain the officer knew he was deaf.

“I’m just going to wait keep my hands on the wheel till the police officer comes up, and I’m going to tell them I’m deaf," Goodner said. "Make sure I have eye contact, I’m not going to reach for anything before they know what I’m doing, because I’m not going to be a number or a statistic."

Historical context and bad cops are hurting good cops and society

The first known traces of policing in America in the North, dates back to 1631 in Boston with a group known as the Watch. In the South, it began with first formal slave patrol in the Carolinas in 1704. Dr. Gary Potter a professor at EKU’s School of Justice Studies said historically policing “emerged as a response to ‘disorder.’” Lewis said that Black, Brown and Indigenous communities have a violent history with police.

Lewis said sometimes people in certain communities might be triggered by their experience of “policing systems in their neighborhood,” or “even just witnessing it time and again online.”

“It causes triggers for people who can self-actualize each of these people who we are literally witnessing being murdered by law enforcement such that our natural response, our natural response as Black and Brown people is to terror," Lewis said, tensing her muscles to re-enact a sense of stress.

Lewis said the fear that some Black and Brown people see in response to police is what she believes causes some people “to fight, run or freeze in the presence of law enforcement.”

But points out these are the same reactions that illicit use of force.

“A lot of the people who are running from law enforcement are fighting for their lives because of the trauma and terror of all of these generations and especially social media and all of these viral videos," Lewis said. "It’s difficult not to have that feeling as a Black or Brown people in this Country that..any interaction with a police officers could very well be your last."

It’s is difficult to quantify police use of force and police violence without any data points.

How use of force with albleism and racism can turn into police violence and brutality

HEARD has been working to compile a list of police violence on the deaf and hard of hearing community and say finding this data is very difficult. But as with police violence with the hearing world, Lewis says police violence on the deaf and hard of hearing disproportionately impacts ethnic minorities.

“All except three were Black or Brown (or) Indigenous. There were several indigenous people,” said Lewis. In an incident with police, an individual with an untreated mental illness is 16 times more likely to be killed by police according to the Treatment Advocacy Center.

It’s important to establish the difference between police use of force and excessive use of force by police also referred to as police violence and police brutality.

There is “no single, universally agreed upon definition for use of force” according to the National Institute of Justice. The International Association of Chiefs of Police describe use of force as the “amount of effort required by police to compel compliance by an unwilling subject,” according to NIJ.

“Broadly speaking, (NIJ defined) the use of force by law enforcement officers (as) become necessary and is permitted under specific circumstances such as in self-defense or in defense of another individual or group.”

In regard to police involvement with the disabled community the “ADA requires that police departments have policies practices and procedures that prepare their officers to work with the disabled community. That officers are prepared to offer reasonable modifications to people in their interactions. And when they don’t we view that as a violation of the ADA,” said Mizner.

Cornell Law School defines excessive force as “force in excess of what a police officer reasonably believes is necessary. A police officer may be held liable for using excessive force in an arrest, an investigatory stop, or other seizures. A police officer may also be liable for not prevention another police officer from using excessive force. Whether the police officer has used force in excess of what he reasonably believed necessary at the time of action is a factual issue to be determined by the jury.”

Police brutality is the “unwarranted or excessive and often illegal use of force against civilians by police officers. Forms of police brutality have ranged from assault and battery to mayhem, torture and murder. Some broader definitions of police brutality also encompass harassment (including false arrest), intimidation, and verbal abuse among other forms of mistreatment,” according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Police violence and brutality are faced by ethnic minorities at a disproportionately higher rate. Native Americans are killed by law enforcement at the highest rate of any racial group in the US.

When it comes to police violence and police brutality “the law doesn’t allow this,” said Mizner. “Racism and ableism intertwine to create heightened fears in the officers.

Mizner said that the perception is that someone who doesn't fit the norm nor is responding in an expected way is considered dangerous, which creates a response.

“And courts have too often said ‘well rational fear, maybe it was OK,’ Mizner said. "And they get away with it."

But again, without data it is difficult to determine at what rate.