JACKSONVILLE, Fla — The classic image of Santa Claus, the big jolly man with a flowing white beard and red suit, may be one of the most recognizable characters throughout the world. Yet, it took hundreds of years to develop what we now know as Santa.

Prior to the 19th century, there were several variations of a Christmastime gift giver. Most of them were based on St. Nicholas of Myra, a 4th century Christian bishop and the patron saint of children. According to Catholic Insight, Christian tradition holds St. Nicholas would offer gifts to children as a form of charity.

This most popular folktale concerning St. Nicholas says he offered to help a poor father and his three daughters, who seemed destined to a life of either servitude or prostitution, the Catholic Insight reports. However, as accepting charity publicly was considered dishonorable in that time, Nicholas went to the family's home three different times to leave gold at their home so the father could pay his daughters' dowries while sparing them the shame of accepting the charity.

Over the centuries, the various European kingdoms told stories of folk characters that delivered gifts to children for Christmas, including Father Christmas in England and Sinterklaas in the Netherlands. However, all these versions of the Christmas gift giver had little resemblance to the modern Santa Claus.

Sinterklass Hudson Valley says it was not until the colonization of America that many of these characters truly combined into a single character that would be widely referred to as Santa Claus. In fact, the name Santa Claus is simply an Anglo translation of Sinterklaas, showing the mixing of English and Dutch culture during the height of the Columbian Exchange and colonization of the North America, Sinterklass Hudson Valley reports.

In 1809, Washington Irving updated the image of Sinterklaas from a bishop to a heavy Dutch sailor with a pipe in his book "A History of New York," a parody of New York’s Dutch population and culture. In the book, the character was notably renamed to Santa Claus. Though the term Santa Claus had been used for several years, Irving’s character helped sever the ties between the modern Santa Claus and the bishop-like Sinterklaas, according to Sinterklass Hudson Valley.

In 1821, the idea of the reindeer pulling Santa’s sleigh was introduced in an anonymously written poem titled "Old Santeclaus with Much Delight:"

"Old SANTECLAUS with much delight

His reindeer drives this frosty night,

O’r chimney tops, and tracts of snow,

To bring his yearly gifts to you."

The accompanying illustrations were some of the first to deviate from the Dutch bishop or Irving’s Dutch sailor. Those illustrations also showed Santeclaus delivering toys in a suit.

However, perhaps most importantly, the poem may have inspired one of the great works of Christmas literature: "A Visit from St. Nicholas," or as it is commonly known today "The Night Before Christmas." The poem, published in 1823, brings back St. Nicholas as the Christmas gift giver, but describes him as a dressed in furs, much like the Father Christmas character from England, according to the tale:

“He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot,

And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot;

A bundle of toys he had flung on his back,

And he looked like a peddler just opening his pack.

His eyes -- how they twinkled! his dimples how merry!

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry!

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow,

And the beard of his chin was as white as the snow."

One of the most important aspects of the poem is that St. Nicholas’ sleigh is pulled by eight reindeer named Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donner and Blitzen. It was the first time the now-iconic reindeer names had been used, according to literature. Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer would not appear until more than a century later in the 1930s.

While the poem introduced several important aspects of the Santa Claus character, including the rosy cheeks, climbing down the chimney and white beard, it did not have any accompanying illustration. Instead, it would be illustrations by an immigrant living in New York City in the coming years that would take the St. Nicholas portrayed in the poem and turn him into modern-day Santa Claus.

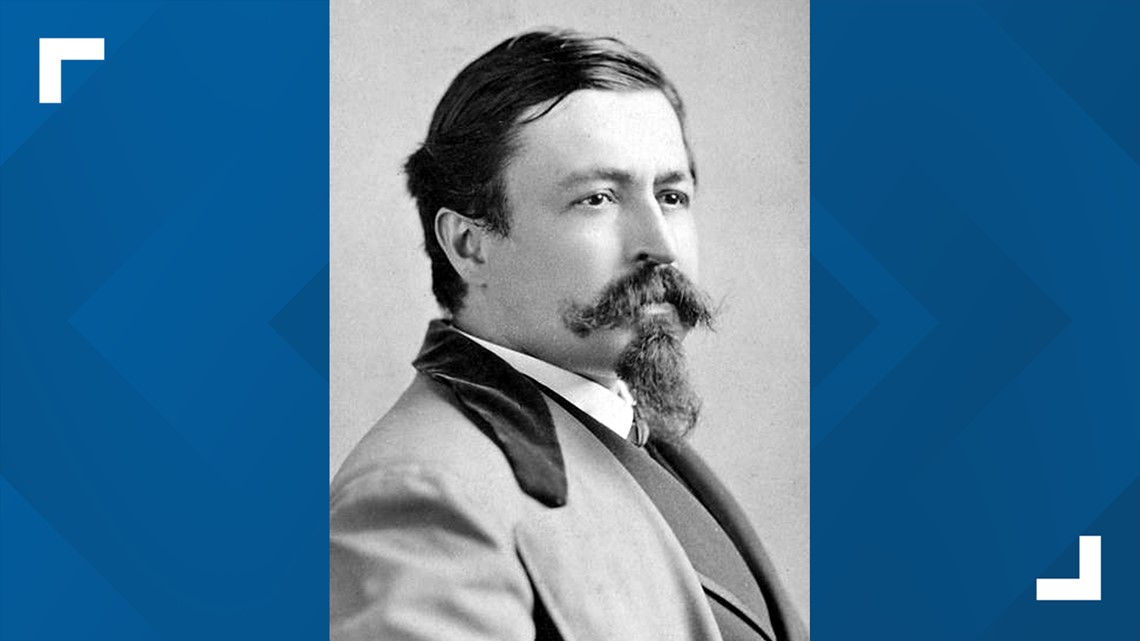

Born in 1840, Thomas Nast immigrated with his family to America from Bavaria as political refugee in 1850. The family settled in New York City, where Nast attended school. When he was 16, Nast began his career in journalism. By 1859, his illustrations and political cartoons would appear in Harper’s Weekly, one of the country’s premier newspapers. His cartoons in the 1870’s are widely credited for helping to expose and bring down the infamous Tammany Hall Political Machine in New York City.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, in 1862, while America was in the midst of a bloody civil war, Nast was a staff cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly. He was staunchly pro-Union, and his cartoons presented the Union cause as a noble endeavor, particular when it came to the freeing of the slaves, while presenting Southerners as bloodthirsty savages, the Smithsonian reports. According to Britannica, Pres. Abraham Lincoln referred to Nast’s cartoons as “our best recruiting sergeant,” while Gen. Ulysses Grant said Nast, “did as much as any one man to preserve the Union and bring the war to an end," according to Smithsonian Magazine.

During four long years of war, Christmas was a period that soldiers on both sides, many of whom had never left home before, found particularly difficult. Still, they found ways to celebrate as best they could by decorating their camps and singing carols with their regimental bands, according to the American Battlefield Trust. There were also stories of Union and Confederate pickets, who guarded their respective camps, exchanging small gifts, an act typically discouraged by their commanders.

“In order to make it look much like Christmas as possible, a small tree was stuck up in front of our tent, decked off with hard tack and pork, in lieu of cakes and oranges, etc,” a Union soldier wrote in his diary, according to the American Battlefield Trust. “We retire to sleep with feelings akin to those of children expecting Santa Claus.”

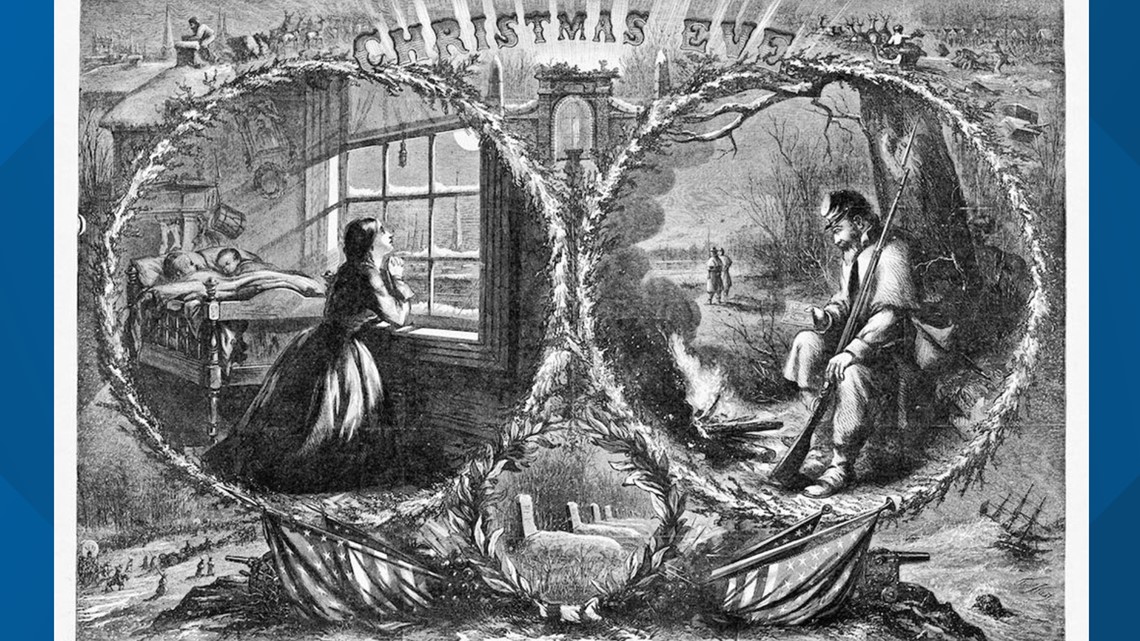

Nast made a point to portray the hardships of spending Christmas on the frontline in his illustration "Christmas Eve, 1862" that appeared in the Jan. 3, 1863 edition of Harper’s Weekly.

The main image, now public domain, presents a soldier on the frontline solemnly praying for his family on Christmas Eve while his wife back home prays for her husband’s safe return with their small children tucked in their bed. Below them is an image of gravestone marking those who would never return home. Depictions of battle on land and sea at the bottom left and bottom right of the image shows the reality of the seemingly interminable war at hand.

Nast drew the image only weeks after the Battle of Fredericksburg, a major defeat for the Union that cost more than 12,000 casualties, including 1,284 killed in action. Morale in the Union camp, huddled along the Rappahannock River, had never been lower. Nast’s image captured the feeling of soldiers at the end of 1862 and their families, who regularly checked their local post office for the lengthy casualty list.

Yet, despite the melancholy image in the foreground, in the top right and top left of the image is perhaps some of the most important developments in the Santa Claus character. On the left side, Santa Claus is depicted as a sort of elf, is climbing into a chimney with gifts in hand. His sleigh and reindeer are seen behind him. On the top right side of the cartoon, Santa is seen again, this time riding by a Union camp on his sleigh. The image shows Santa throwing gifts to grateful soldiers who are chasing the sleigh. These small images help to present that despite the horrors of war, Santa Claus still did his annual duty of delivering gifts.

However, the Santa Claus in the drawing had a brown beard and was not fat, as we imagine Santa Claus now. In fact, Santa Claus in that drawing is said to be based on Nast himself, with his family inspiring the images of the other characters. Yet another Nast illustration in the same Jan. 3 edition of Harper’s Weekly would be a slightly different version of Santa Claus.

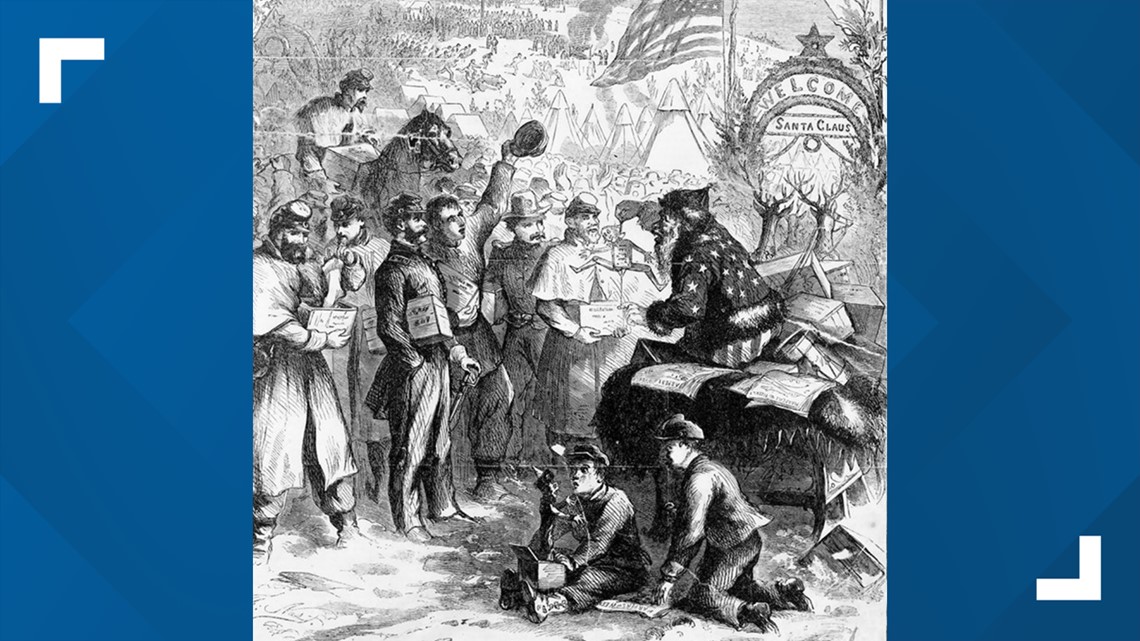

The picture, titled Christmas in Camp, shows a white-bearded, elf-like Santa Claus wearing an American flag coat and hat, as he distributes gifts to joyful soldiers in a Union camp. It is a noticeably different tone than the Christmas Eve image.

In the back to his right is a wreath that proclaims, “Welcome Santa Claus.” Some of the gifts include a jack-in-the-box, editions of Harper’s Weekly and a macabre depiction of a man, believed to be Confederate Pres. Jefferson Davis, hanging from a noose from Santa’s hand, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

By 1866, after the Civil War had ended, Nast had modified the image of Santa Claus into a jolly, heavy-set old man with a long, thick white beard. In the December 1866 edition of Harper’s Weekly, Santa Claus can be seen in his workshop in one panel and carrying a large bag of toys near a fireplace in another panel. A panel also shows him hanging gifts on a tree, an old Christmas tradition that pre-dates presents underneath the tree.

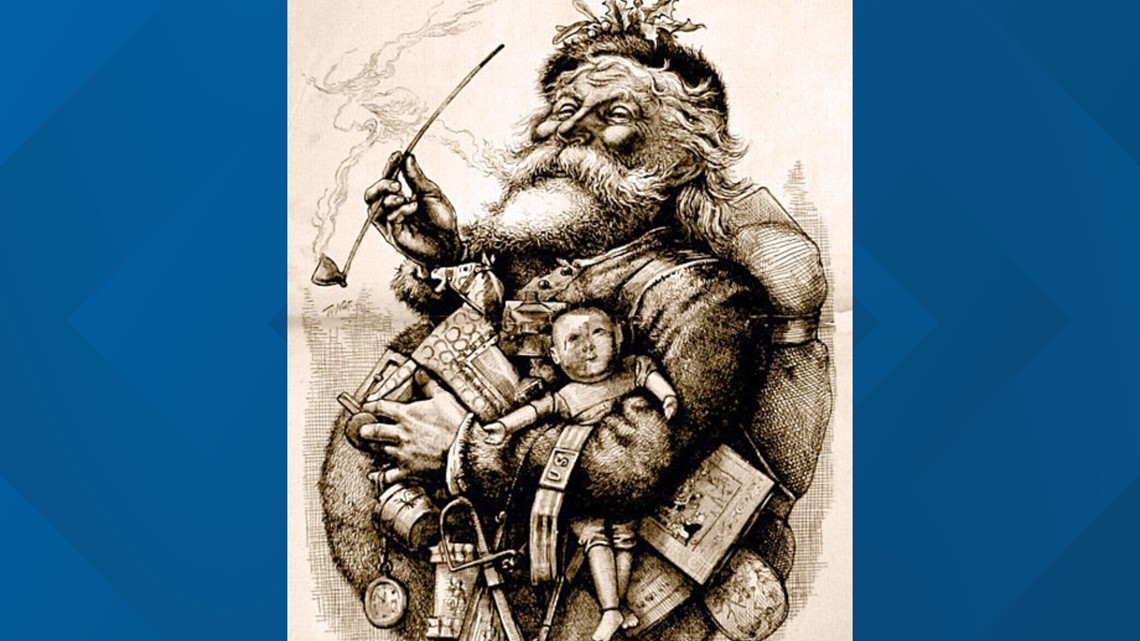

According to the Smithsonian Magazine, Nast would illustrate more than 30 images of Santa Claus during his career with Harper’s Weekly. The most famous of these is his 1881 Merry Old Santa Claus. The image is instantly recognizable as a modern Santa Claus, though in this illustration, his bag is replaced with an Army sack, he is smoking out of a pipe and his clothes are still fur, remnants of previous depictions, including Father Christmas and the Dutch sailor.

Nast’s last published Christmas illustration was in 1886, shortly before his departure from Harper’s Weekly. By then, he had either invented or modernized several now-iconic American images, including the Democrat donkey, the Republican elephant and Uncle Sam’s goatee, the Smithsonian reports. Yet, it is his depictions of Santa Claus that is perhaps is most lasting legacy in popular culture. However, Santa Claus had a few more developments to make over the next century.

By the 1930s, Santa Claus had been given a wife, known simply as Mrs. Claus. His home of the North Pole had been firmly established and the character was recognized as immortal. But the last developments of Santa Claus would be cemented by the Coca Cola company in the earliest series of perhaps the most widely known Christmas campaign.

According to Coca Cola, in 1931, the company commissioned illustrator Haddon Sundblom to depict Santa Claus for a holiday advertisement. Sundblom’s version of Santa Claus showed a more human-looking Santa with rosy red cheeks, a warmer personality and most importantly, with a red suit. Sundblom painted the iconic image of the now-standard Santa Claus drinking a Coca Cola from its famous glass bottle until 1964.

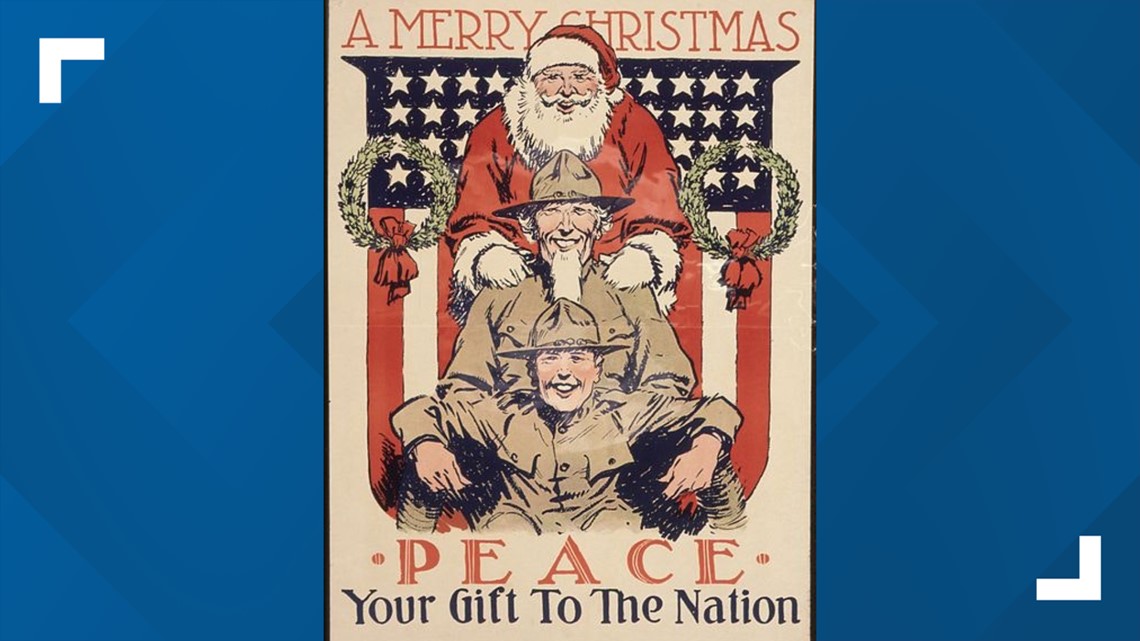

However, Sundblom’s image was by no means original. The Public Domain Review said numerous images depicting the character as jolly and human-like, instead of elf-like with a large body in a red suit appeared in advertisements, magazines and even several World War I propaganda posters.

“A standardized Santa Claus appears to New York children. Height, weight, stature are almost exactly standardized, as are the red garments, the hood and the white whiskers,” the New York Times wrote in 1927. “The pack full of toys, ruddy cheeks and nose, bushy eyebrows and a jolly, paunchy effect are also inevitable parts of the requisite make-up.”

Even pre-1930's Coca Cola ads used the red-coat look. Yet, according to Coca Cola, the company's previous attempts at capturing a warm, inviting character were unsuccessful and never fully caught on. Sunblom’s 1931 panting and his subsequent depictions of the character in Coca Cola ads marked the last major development in the Santa Claus character and help solidify his appearance and personality.

It did not take long for his depiction to take root while the film and television industry boomed. Tens of thousands of people watched Sundblom’s Santa Claus come to life in Coca Cola advertisements from the 1950’s. During that same time, depictions of our modern Santa Claus in films like “Miracle on 34th Street” and “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” brought many of the literary characteristics to life, like his deep Ho-Ho-Ho cheer.

Throughout the years, artists in different forms would add their own spin on the Santa character. Songs like “Santa Baby” and “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus” portrayed Santa Claus in a more promiscuous light. Meanwhile, The Beach Boys interpreted Santa's sleigh as a hot rod in their famous Christmas hit "Little Saint Nick."

The children’s book "The Polar Express" invented the image of a train pulled by a steam engine taking kids to the North Pole on Christmas Eve to receive the first gifts of Christmas. "Elf" with Will Ferrel portrayed Santa’s sleigh as being powered by people’s belief in him. Films like "The Santa Claus" with Tim Allen and "Ernest Saves Christmas" show Santa Claus not as single, immortal person, but a job title to be inherited by future generations.

Even NORAD has put their own mark on the Santa Claus character through their annual NORAD tracks Santa, which shows his flight from the North Pole to children’s houses throughout the world.

From cruising in on a float during the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade to accepting children on his lap at shopping malls across the country, each year, Santa Claus brightens up the holiday season for millions of people around the world. His image instantly brings up feelings of excitement and anticipation for children, and nostalgia for adults.

Perhaps the best way end any story of Santa Claus is to offer a quote from an editorial that appeared in the New York Sun in 1892.

Virginia O'Hanlon, then 8 years old, wrote to the popular newspaper at the behest of his father:

“DEAR EDITOR: I am 8 years old.

Some of my little friends say there is no Santa Claus.

Papa says, ‘If you see it in THE SUN it’s so.’

Please tell me the truth; is there a Santa Claus?”

Veteran journalist Francis Pharcellus Church, a former Civil War correspondent known for dismissing religion and superstition, instead responded with a kind and warm editorial in what has become the most reprinted newspaper article in history:

“Yes, VIRGINIA, there is a Santa Claus. He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy.”