Uncovering the brutal history of Native boarding schools in Indiana

While the U.S Department of the Interior plans to release a report on residential schools, DNR will look closer at how many lives were lost in Indiana.

For a 14-year span in the late 19th century, the federal government worked in tandem with religious organizations to send hundreds of Native American children to two off-reservation boarding schools in Indiana.

Thousands of miles away from their families, and operating inside a structure dedicated to the eradication of their identity, the boarding school system used children as pawns in the federal government's overall strategy to destroy Native American communities through the policy of assimilation.

At the height of the off-reservation boarding school era, more than 350 institutions operated across the United States. Attendance at these schools did not only mark a spiritual or cultural death for Native children. It very often marked a physical one.

Dozens of children who lost their lives at these schools remain buried near or on, the grounds of those institutions — more than a century after they closed.

Now, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources is investigating whether there could be more innocent victims whose lives ended in the thralls of this lethal system and who remain unaccounted for across the state.

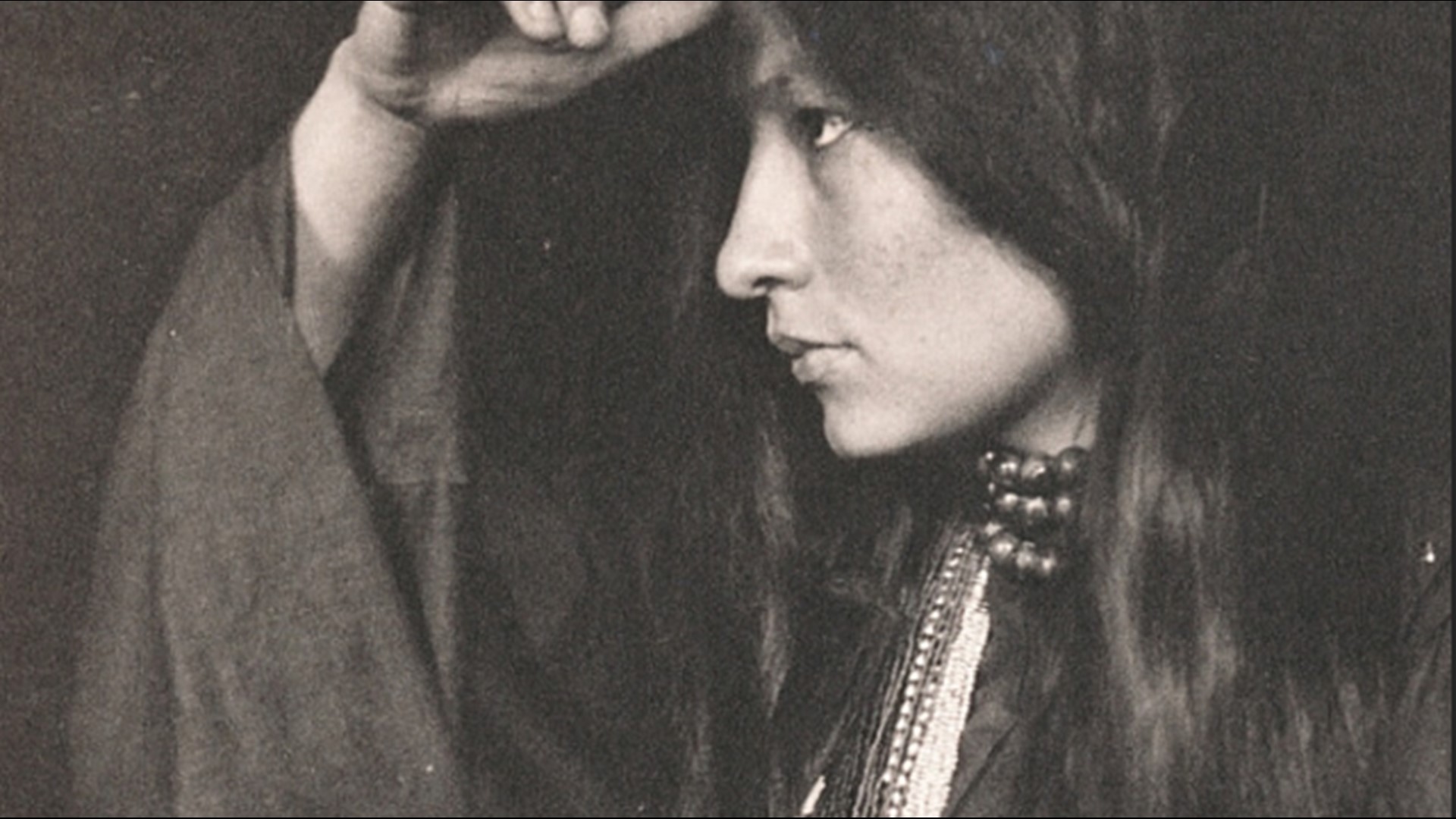

Zitkála-Šá was 8 years old in the spring of 1884, when Quaker missionaries came to her home on the Yankton Indian Reservation in Dakota Territory.

The well traveled men spoke of a mysterious, far eastern land they called Big Red Apple Country.

They wanted Zitkála-Šá , as her older brother had three years prior, to get on a train and go with them.

Despite her mother's hesitations, the men eventually persuaded Zitkála-Šá's mother this would be in her child's best interest. White settlers had already begun to encroach on that land in Dakota Territory, and perhaps an education out east would give Zitkála-Šá a chance for survival.

Zitkála-Šá, not fully aware of what going with the men meant, begged to go with them and was put on a train with eight other children.

"Soon, we were being drawn rapidly away by the white man's horses. When I saw the lonely figure of my mother vanish in the distance, a sense of regret settled heavily upon me. I was in the hands of strangers whom my mother did not fully trust," she later wrote.

When Zitkála-Šá eventually did set foot on those lands a few days later, icicles clung to bare trees where she had been told red apples would grow.

Within days, she faced abuse typical of the boarding school system.

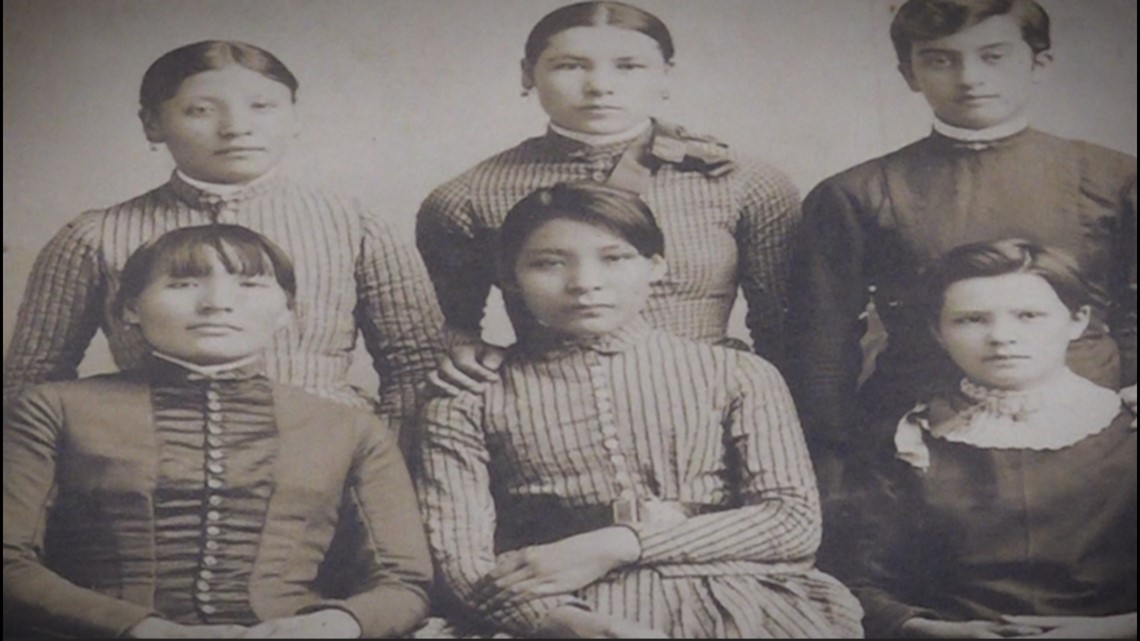

Her clothes were taken from her, replaced with the standard uniform everyone else wore. When she began to cry over a bowl of porridge, an older student whispered, "Wait until you are alone in the night."

The next day, school officials cut Zitkála-Šá's hair. Growing up, she only saw people in mourning, or people who lost in battle, cut their hair. She hid under a bed to avoid the violation, but school officials strapped her to a chair and took it by force anyway.

"I cried aloud, shaking my head all the while, until I felt the cold blades of scissors against my neck, and heard them gnaw off one of my thick braids," she wrote. "Then, I lost my spirit."

Zitkála-Šá's testimony of her time at White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute, detailed in her 1921 memoir "American Indian Stories," is one of the only surviving student perspectives that recounts what brutal conditions hundreds of children endured at that school — the older of two institutions established in Indiana during the off-reservation boarding school era of the United States.

Utilizing institutions under the guise of education to strip Native Americans of identities and culture throughout generations predates the United States.

As early as the mid-1600s, a smattering of missionaries worked to establish religious schools across New England, intentionally placing those institutions near indigenous communities in an effort to further spread Christianity, and destabilize native culture.

Although European farming practices likely would not have survived had they not been implemented on ancestral lands indigenous people cultivated for centuries, the federal government was eager to rid them of it.

Having forced thousands of tribes onto reservations in the western United States by the early 1800s through a series of broken promises and faulty treaties, the federal government moved fast to adopt a harsher iteration of the assimilation framework previously established by churches.

Day schools were set up on reservations as a way for the United States government to further their influence within Native American communities, in the hopes of eradicating ways of life for hundreds of tribes.

By 1819, the government had provided its first allocations for boarding schools with the Civilization Fund Act.

But government officials were displeased by how close children remained to their families at those locations. Seeking to further disrupt whole tribes more permanently, the government implemented a new strategy for children.

It was the brain child of a U.S. army sergeant charged with overseeing 72 Native American prisoners of war at Fort Marion in Florida.

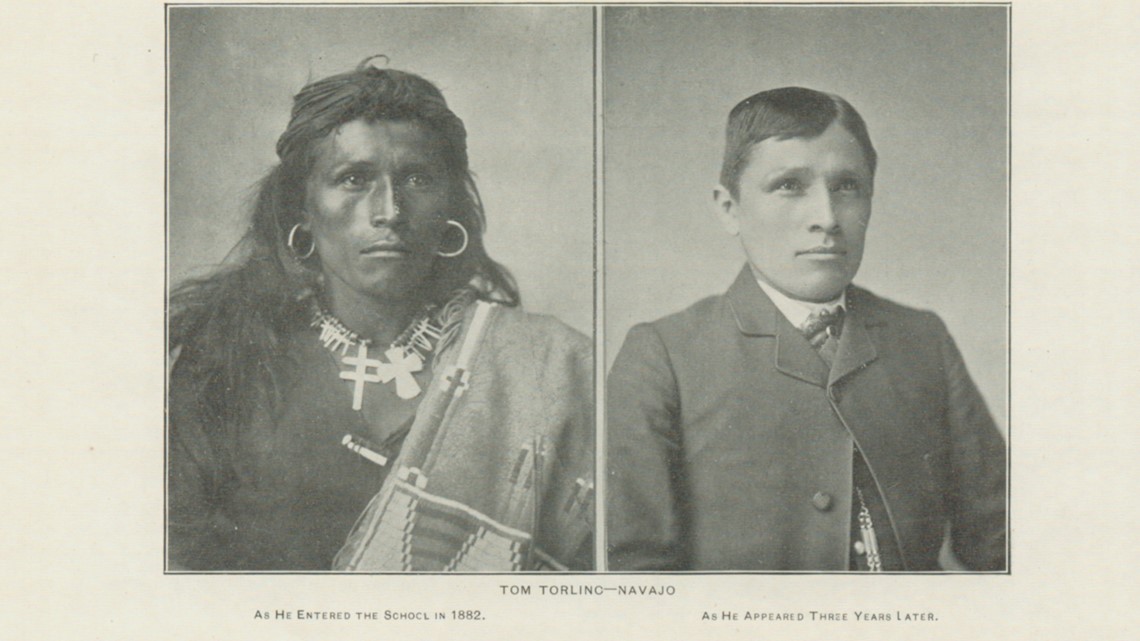

"A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one," U.S. Army Captain Richard H. Pratt said. "In a sense I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: That all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him and save the man."

Pratt's common refrain, 'kill the Indian, save the man' was later embedded into the curriculum at the boarding school he persuaded the federal government to build.

"He was a war criminal. His whole idea of killing the Indian and saving the man was so detrimental to generations of people, generation after generation after generation of people, just dealing with what he created," Meg Singer, a producer and Native American Initiative Director at Utah Valley University, said.

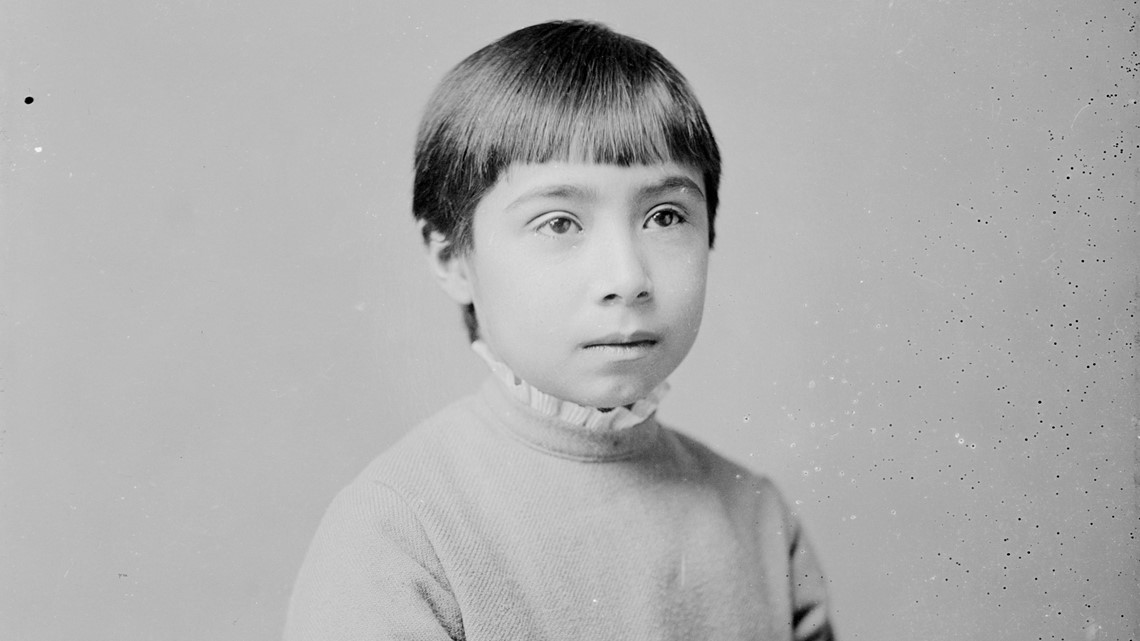

By 1879, the army barracks at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, were converted into an "Indian school" as a way to force children into culturally assimilative practices.

Once within the walls of Carlisle Industrial School for Indians, children were subjected to physical and sexual abuse, forced to convert to Christianity, and beaten for speaking their own language. Their heads were shaved. They often died from sickness and endured psychological trauma.

In January 1880, a cemetery was established — four months after the school opened.

"What sort of high schools have cemeteries? This is not normal. Generally, children are the healthiest demographic of any population. Children just — don't die. And so, something must have been precipitating these deaths," Preston McBride, a postdoctoral research fellow of Native American and Indigenous Studies with the University of Southern California, said.

McBride's research focuses on health and environmental situation students endured at some of the largest residentials schools in the country. It found conditions within those institutions were not suited for survivability. Institutions underreported the deaths of students, or intentionally left them out of the records.

"Ultimately the federal government doesn't care about the deaths of indigenous children in their custody. This is all part of, number one, the belief that indigenous people are just going to die out naturally — kind of the disappearing Indian myth. But also, these children are acceptable collateral damage from the government's perspective," McBride said.

Carlisle, despite the human rights atrocities that were recorded there, fast became the standard for other boarding schools across the country.

It wouldn't be long until these genocidal curricula, implemented at more than 350 institutions nationwide, made their way to Indiana.

White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute

Quaker missionaries established White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute in Wabash three years after Carlisle's was founded.

The White Institute Board of Trustees purchased more than 600 acres of land directly from the Miami tribe upon which to build a school for poor children. The first classes began on the premises in 1862, but 20 years later, the school faced financial distress.

In 1882, the board moved to approve a plan that would turn the existing White's Institute into an "Indian training school" — a move that allowed them to start accepting $167 per year for every Native American student brought to the school from reservations. That equals about $4,645.15 per year in 2022.

The surplus of federal funds that accompanied a certain quota of Native American children could, White's administrators deduced, help them stay in operation.

Historians John W. Parker and Ruth Ann Parker recalled finding evidence missionaries affiliated with White's, the same men who encouraged Zitkála-Šá to come to Indiana, often took manipulative liberties to recruit enough students they needed to receive government funds, in their book "Josiah White’s Institute: The Interpretations and Implementation of His Vision."

Native American parents were not always properly informed of the terms of their children's enrollment. Once the children were at the school, it was sometimes impossible to get them back.

Parker also found evidence in school archives that the children's parents, unaware of those terms of enrollment, pleaded with White's leaders to return their children to their care. Those pleas were often ignored.

"The Indian agent would normally choose to keep the child at school," Parker wrote.

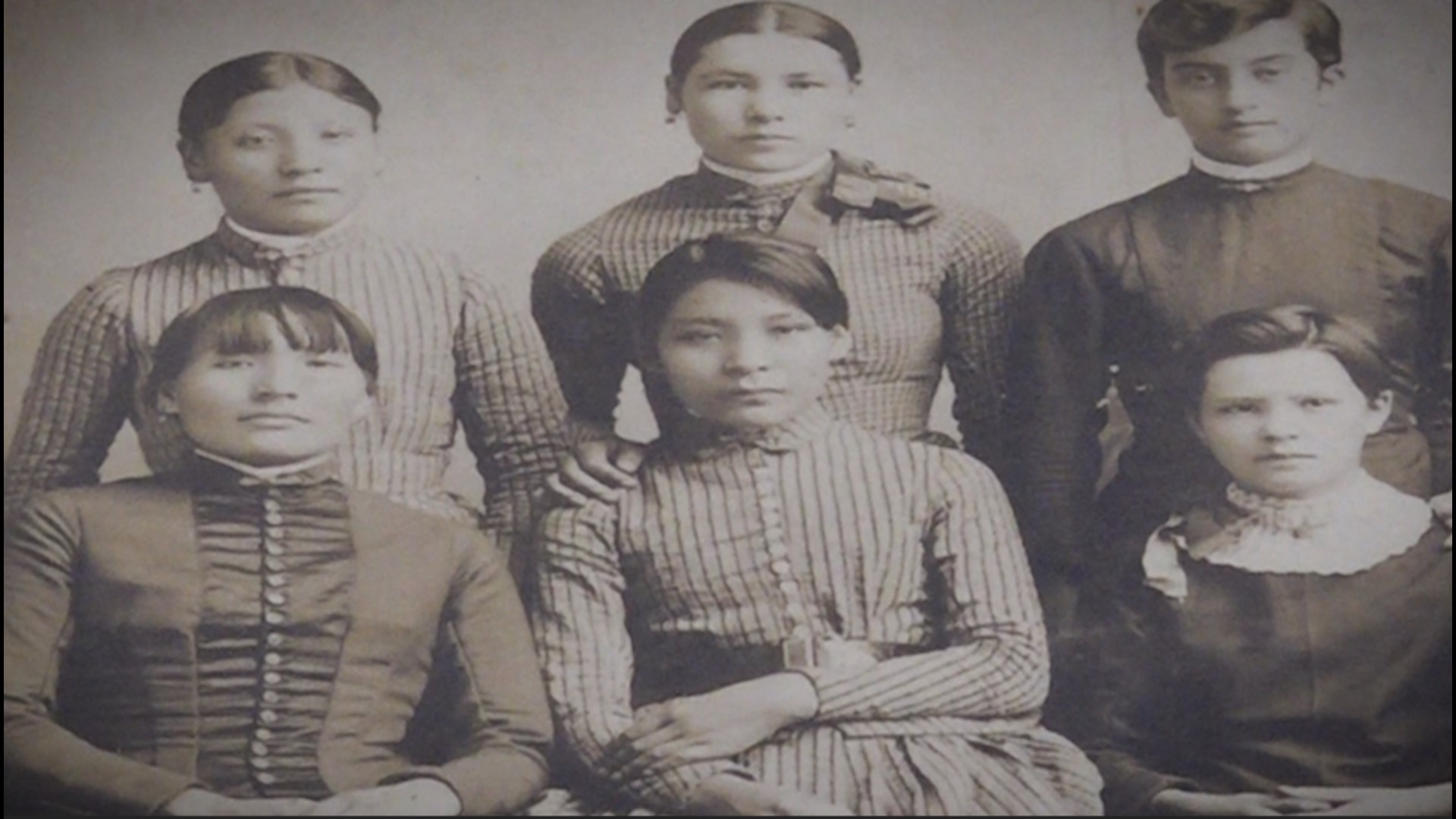

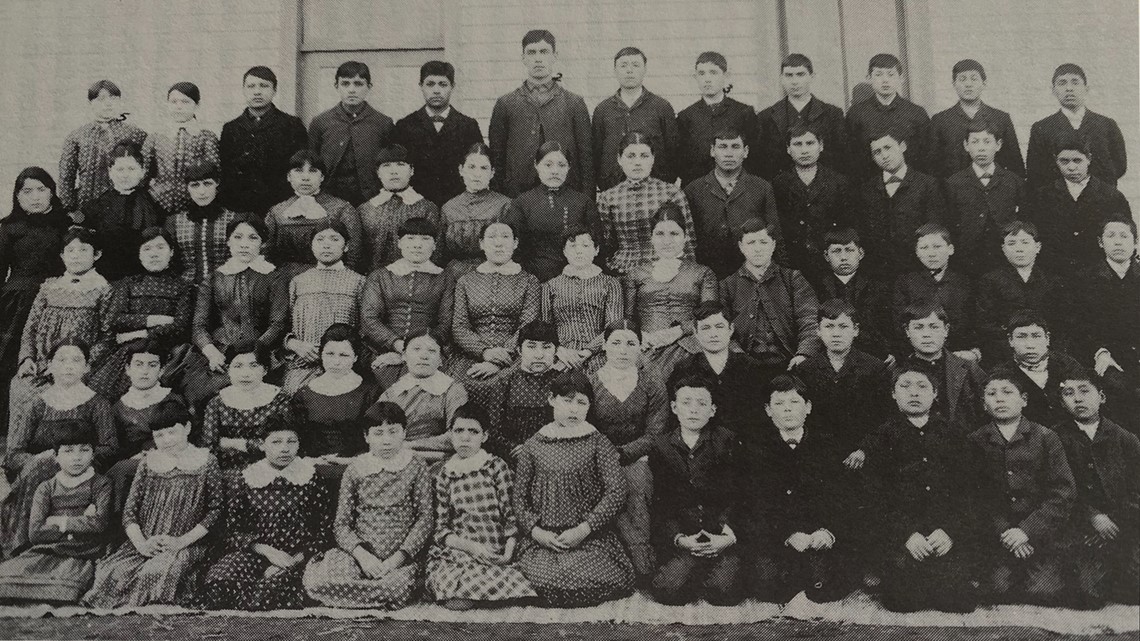

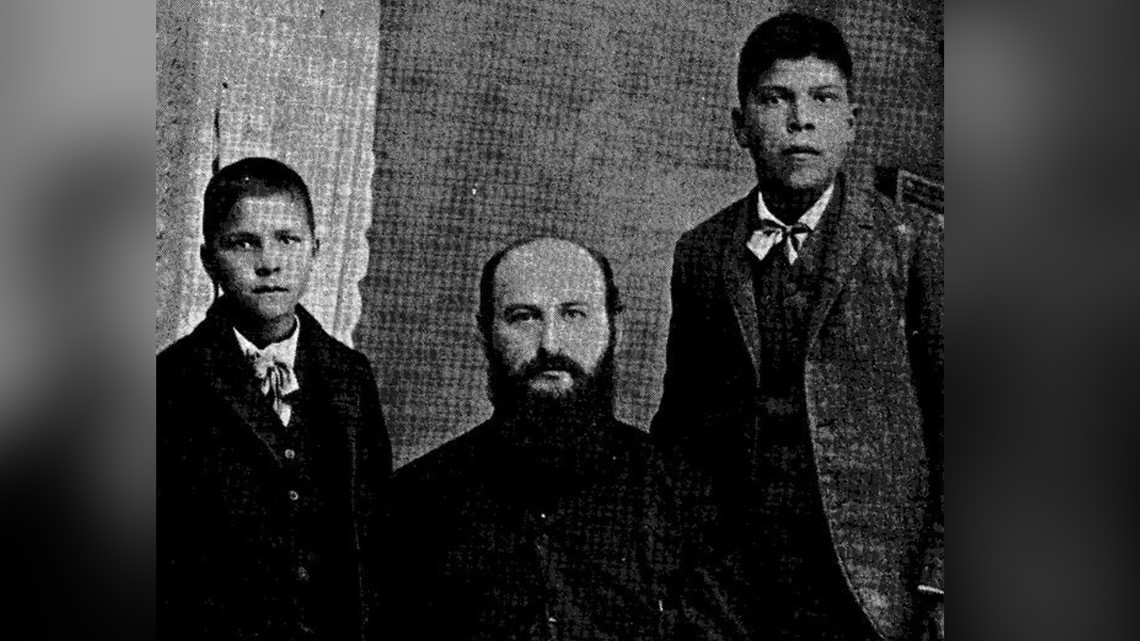

It is within this context that 27 children — 16 boys and 11 girls — were brought from their parents arms and into those of staff members' in Wabash.

School archival records provided to 13News from White's Residential and Family Services, which still exists on the same grounds today as a Christian-based residential school affiliated with the Indiana Department of Child Services, show at least 200 more Native children would attend White's between 1883 and 1895. Although, there could be more students not accounted for within those records.

Enrollment entry rosters from 1883 to 1891 obtained by 13News show Indiana's involvement in the off-reservation boarding school system impacted the lives of Native American children and families across the country. Sac and Fox, Potawatomi, Modoc, Seneca, Shawnee, Ottawa, Quapaw, Wyandotte and Cheyenne children were all in attendance at White's.

The school enrollment entry roster shows a majority of the children enrolled at White's came from Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota, where Zitkála-Šá was born. She is listed in school records as Gertie Simmons — her given name was Gertrude Simmons and she changed it to Zitkála-Šá as an adult.

If children initially felt unique upon entering White's, they were soon given just one identity: Indian.

According to Zitkála-Šá accounts, their languages were prohibited. She remembered how a fellow classmate was beaten in the snow by a "paleface woman" for not understanding the word "no."

"The poor frightened girl shrieked at the top of her voice when she was hit," Zitkála-Šá wrote. "During the first two or three seasons, misunderstandings as ridiculous as this one of the snow episode frequently took place, bringing unjustifiable frights and punishments into our little lives."

Zitkála-Šá considered running away several times. While some students were able to return home to reservations, it was highly contingent on school officials. Three boys ran 37 miles away to Logansport in the summer of 1895, and were forced into isolation from the rest of the school as punishment.

A typical term of enrollment at White's was usually three years long, throughout which time students would suffer through 10-hour work days. Boys were trained to be common laborers, while girls were trained as housewives.

Despite the missionary's promises of an enhanced education at the facility, students spent most of their day performing manual labor.

"Rising at 5 a.m., they prepared for the day, did some housekeeping chores, had breakfast and morning devotions, and were ready for the day's activities by 7 a.m. Half the day was spent in the schoolroom and half on the farm," the Parkers wrote.

Tardiness, even for sick days, was not allowed despite the prevalence of deadly diseases at these boarding schools.

Trachoma and tuberculosis especially ran rampant at these institutions across the country, and there is evidence within White Institute's records that the school was no different. The Parkers noted a rash of disease causing sore eyes broke out in 1885.

"Trachoma is a debilitating eye disease that often causes blindness. And they had all sorts of really, really crazy treatments — like cutting off eyelids. It was very nasty stuff. And so, students can't study because they can't read. So the schools said, you know what? You can't read, but you can still lift up a shovel or an ax. And you can still work," McBride said.

White's school officials noted in checkups with multiple students after their term of enrollment ended, that they were afflicted with "sore eyes" or suffered from poor health many years later.

McBride's research aligns with the testimony of Zitkála-Šá, who recalled school officials were unwilling to compromise their strict schedule for sickness.

"No matter if a dull headache or the painful cough of slow consumption had delayed the absentee, there was only time enough to mark the tardiness. It was next to impossible to leave the iron routine after the civilizing machine had once begun its day's buzzing," she wrote.

Illness did not guarantee a return home because written communication between parents and their children often only took place through Indian agents, who enforced policies of the federal government on reservations.

One father reached out to an Indian agent saying his daughter had been taken to White's without his consent or knowledge, and that he was also receiving letters from her that she was very ill, but was not able to convince Indian agent Captain Charles Penney that his daughter should return to his care.

"If some means could be devised to prevent pupils from writing letters of this sort to their parents, it would be a matter of great satisfaction to the agent here. The children are in the habit or writing that they do wish to come home. The parents...are always in favor of the child coming home. These complaints...avail to nothing," Penney wrote to White's superintendent Oliver Bales in 1894.

When one student was sent to Chicago to give birth after becoming pregnant at the school, Indian agent Captain George Leroy Brown advised Bales that he should not make plans to notify her parents.

"I do not deem it well to cause any unnecessary excitement by making this fact known to (her father)...I would recommend you take the girl back to your school after her confinement and place her child in some orphan's asylum in Chicago or some other city to be raised," Brown wrote in 1893.

This disregard for children's well-being wasn't just playing out in correspondence between White's officials and Indian agents on reservations. Zitkála-Šá recalled how one classmate languished until, one day, she could not lift her head from her pillow.

"At her deathbed I stood weeping, as the paleface woman sat near her moistening the dry lips….I grew bitter, and censured the woman for cruel neglect of our physical ills," Zitkála-Šá wrote.

But Zitkála-Šá found ways to resist the situation. Ruining a batch of turnips she was made to prepare for dinner, or smashing jars, were small ways she resisted school officials.

Zitkála-Šá was eventually able to return home to Yankton Reservation to visit her mother after three summers at White's Institute, along with a few other classmates. She pained during that visit how her friends' experiences at different boarding schools across the country had broken them away from their way of life.

"That moonlight night, I cried in my mother's presence when I heard the jolly young people pass by our cottage. They were no more young braves in blankets and eagle plumes, nor Indian maids with prettily painted cheeks. They had gone three years to school in the East, and had become civilized. The young men wore the white man's coat and trousers, with bright neckties. The girls wore tight muslin dresses, with ribbons at neck and waist. At these gatherings they talked English," she recalled.

But during that same year in 1887, another religious order was eyeing plots of land 70 miles of Chicago upon which to establish a boarding school.

The goal of that institution would be to sever more children from their cultures.

But documents show the continued resistance of students forced to attend school there, that same spirit of revenge motivating Zitkála-Šá through her time at White's Institute, played a part it's eventual undoing.

St. Joseph's Indian Normal School

Five years after White's was established in Wabash, the Catholic Church was eager to spread it’s influence in Indiana, and would utilize the federal government’s exploitation of Native American children to do so.

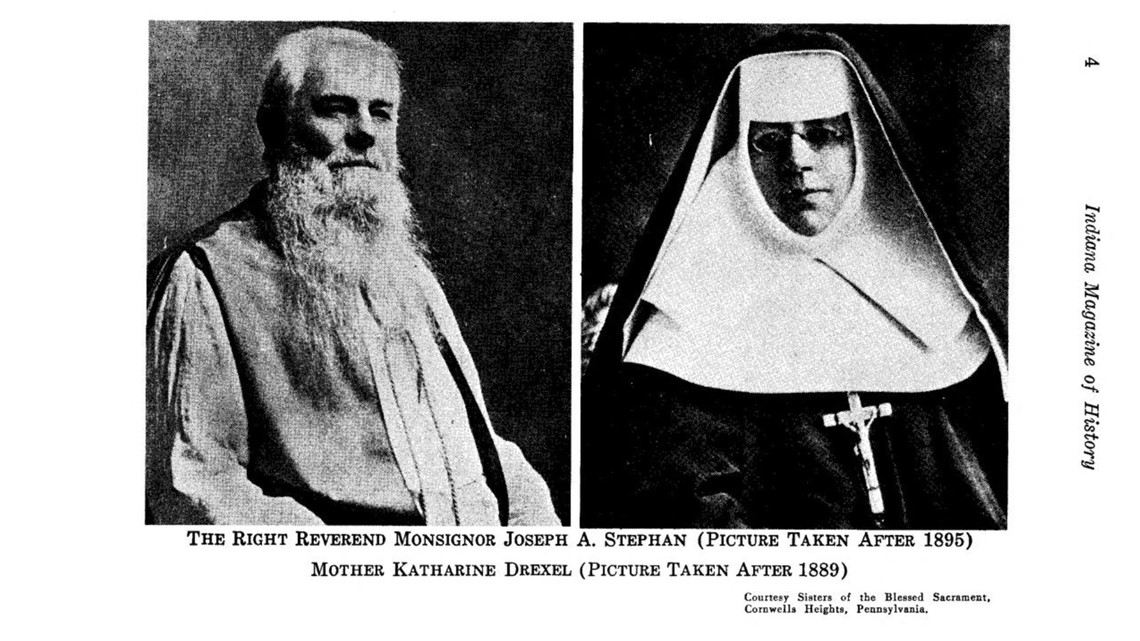

Disturbed by what they saw as the rise of various Protestant groups who were creating a foothold in the Midwest, the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions began to expand its boarding school activities under the direction of an enthusiastic new director from Fort Wayne, Father Joseph A. Stephan.

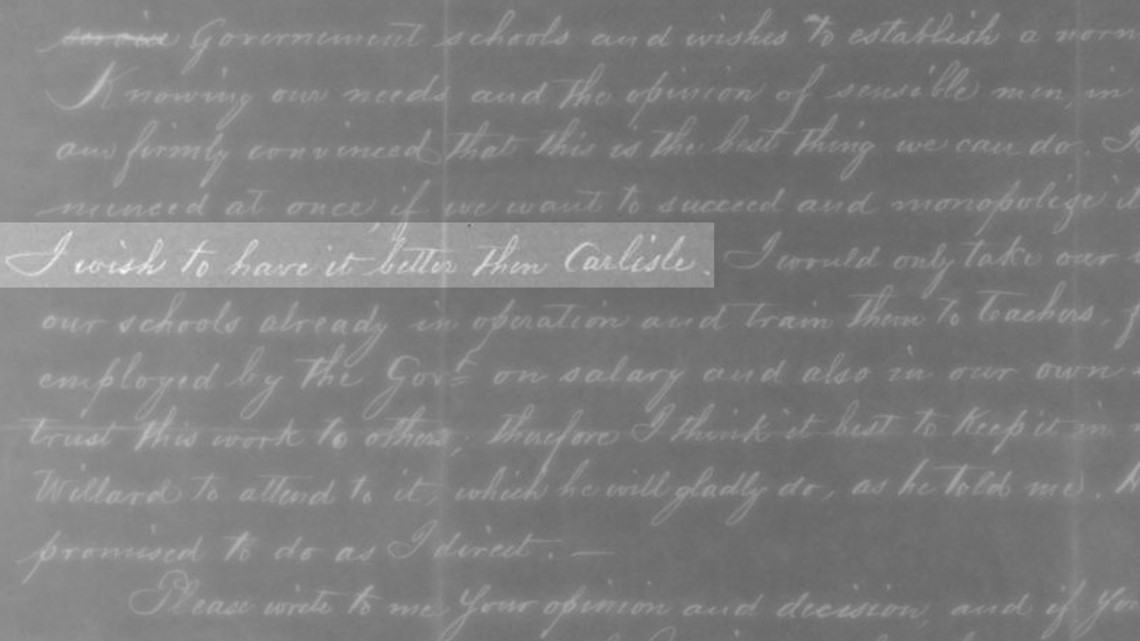

"I cannot sleep. I am firmly convinced that this is the best thing we can do. It must be done well and commenced at once, if we want to succeed and monopolize it. This is very important! I wish to have it better than Carlisle!" Stephan confided to a nun in 1886.

That nun, Sister Katharine Drexel, had more than an unwavering faith in the Holy Spirit to see the duo's shared vision of a Catholic school for Native American children to fruition.

She had cash — around $14 million inherited from her steel tycoon father — to purchase a piece of land upon which to build the school.

Father Dominique Gerlach wrote about the school one of few surviving histories about the institution, in the book titled "St. Joseph's Normal School for Indian Boys" in 1973.

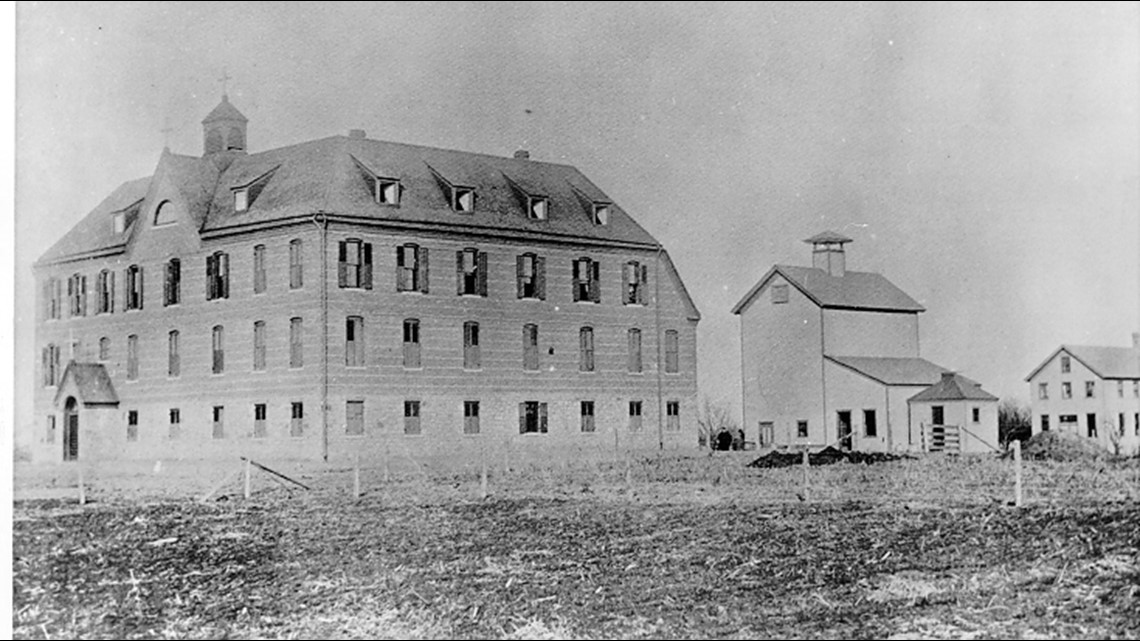

According to Gerlach, it was Drexel who provided the necessary funds to build a large barn, corncribs, and pigpens on the school grounds in Rensselaer. There was a brick house on the property, designed to house up to 100 boys and had 29 rooms in total. Those cost an estimated $50,000 dollars.

Catholic recruiters were soon headed to reservations in an attempt to persuade students to get an education in Rensselaer for the St. Joseph's Indian Normal School. In the late 1800s, normal schools were institutions that trained students to be teachers. The intent was that children from reservations would be trained at St. Joseph's in a variety of trade skills and as teachers, then travel back to their homes and bring Catholicism into those communities.

One recruiter recalled how the students had to be manipulated, fed and entertained to keep them willing to continue the trip.

"Some of the Indian boys, overcome with homesickness, would watch their opportunity and leave the train at some station and hurry back on foot to the reservation," one missionary wrote.

By Oct. 30, 1888, St. Joseph's Indian Normal School in Rensselaer had admitted its first group of students.

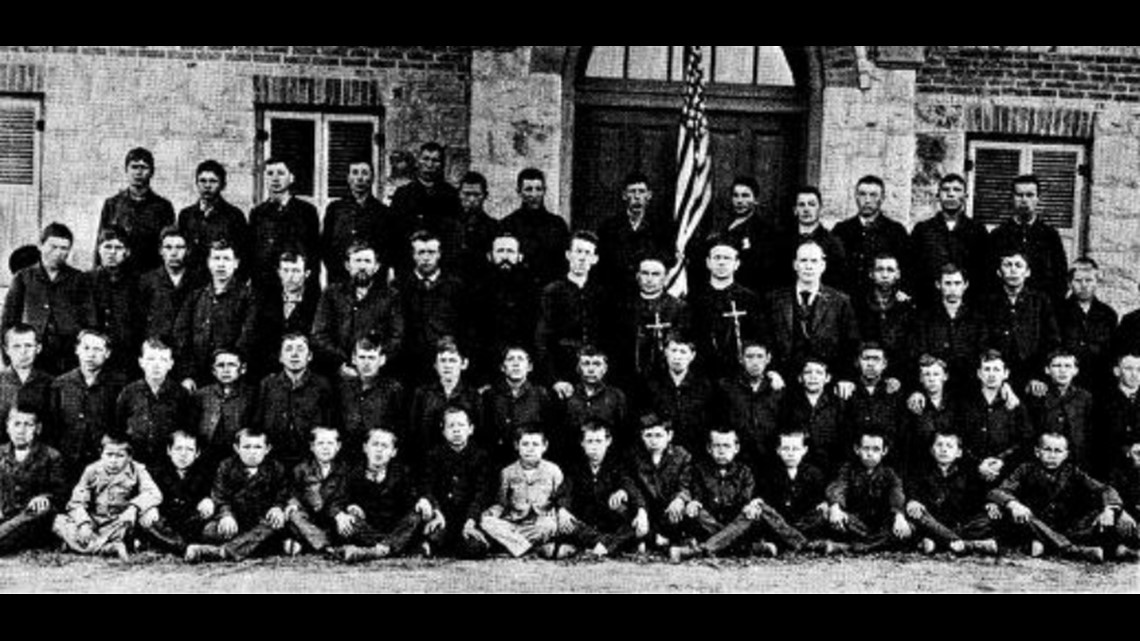

Unlike White's Institute, St. Joseph's only admitted male students — a demographic Catholic officials believed was better suited to uphold white society's ideals of work.

In the school's first year, St. Joseph's archival records show 12 of the 50 pupils ranged from ages 18 to 21, with one 24-year-old in the mix, as well.

Predominantly represented at St. Joseph's were Potawatomi, Menominee, Sioux, and Chippewa children.

St. Joseph's Indian Normal School had two ways of generating incoming: government contracts, which could provide a stipend, and produce from the farm itself. That meant despite the school being initially funded with money from a woman who was an heiress millions of times over, forced student labor was partially propping up the institution financially.

McBride's research found federal funding for these schools stayed the same for decades. Laborious, often life-threatening student labor made up that shortfall.

"I can't tell you how many letters and doctor's positions reports that I find of arms, legs, appendages just being ripped off, mangled beyond belief, amputations of little girls injuries and burns explosions. There there are deaths from gas explosions in kitchens. There is just so much death and maiming that goes on, essentially because these children are not...they shouldn't be there in the first place," McBride said.

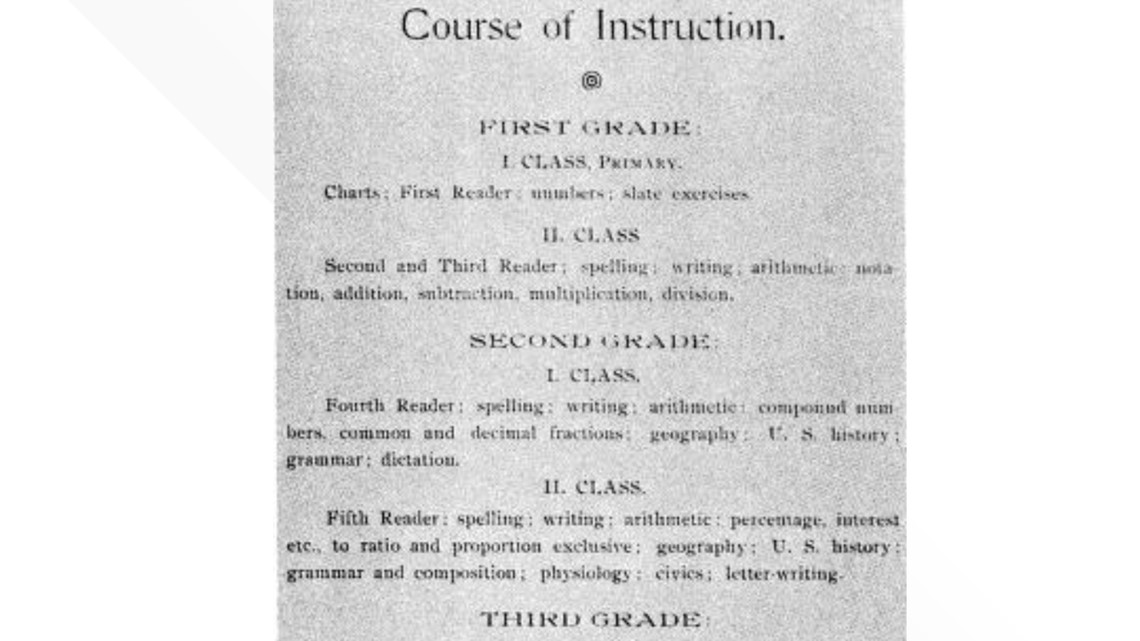

St. Joseph's students chopped wood, and hauled it for fuel before beginning their lessons, according to a school pamphlet.

Records show the children likely labored in deplorable conditions. One government inspector found the bedding "dirty" and the classrooms had "disgraceful old benches," "undecorated," and "cheerless." Officials also pleaded with Drexel to provide proper clothing and furniture for the boys.

One inspector observed that the boys "seem to expect to work and are doing more manual labor than in any other Catholic school of my acquaintance." They also noted the boys intensely disliked work.

A curriculum pamphlet shows it favored unskilled labor over trade schooling or formal education, and took place over the course of a more than twelve hour work day.

"Much of the labor at the school was actually performed by the Indians themselves. Even the majority of the clothing and shoes were manufactured at the school. This was also true of some of the wooden furniture, including desks and benches," Gerlach wrote.

Although students spent over half their day performing manual labor, McBride's research into other institutions found it is unlikely they received proper nutrition.

"The fact of the matter is, the amount of labor they perform is on par with people in the military. They have the same caloric demands. So you have these students laboring, basically in conditions of malnutrition, and it leads to very poor outcomes," McBride said.

If school officials ignored the physical toll students endured, they could not ignore the emotional one. School officials at St. Joseph's were well aware of the impact Indiana's distance from western reservations had on its young students.

"The greatest drawback of the institution arises from the great distance from the Indian homeland, for there are no parents who hang with greater tenderness to their children than these Indian fathers and mothers, and a forced separation appears to them to be a fearful thing," one superintendent wrote to a contemporary.

Escape was ever present. School officials eventually took cruel measures to ensure compliance among the students. They slept in the dorms with them or forced them to turn in specific items of clothing, like coats, in the middle of the winter to deter escape.

Sixteen students tried to escape one year, and one boy walked all the way to Wisconsin. At least one student died trying to escape.

Of the first group of 50 students at St. Joseph's, only six completed the full five year term of enrollment. High pupil turnover rates combined with decreased government funds put a financial strain on the institution.

Even though speaking their Native language, and embracing customs they grew up with were banned, school officials set those technicalities aside when it came time to raise funds.

Students were made to perform in native regalia for the greater Rensselaer community as a form entertainment. Despite the financial troubles of St. Joseph's, school officials were eager to present another face to the world.

In 1893, at least 30 students were put "on display" within a school exhibit at the Chicago World's Fair Exposition, to highlight how "the formerly savage Indian was becoming civilized."

Two years later, in 1895, a new commissioner of Indian Affairs informed St. Joseph's officials that its contract would not be renewed. Congress had reduced appropriations for contract schools, and St. Joseph's was cut off from that funding because of its distance from the reservations. Travel, officials thought, was too expensive.

After six years, St. Joseph's ceased operation as a boarding school for Native American children. At the time, school officials blamed anti-Catholic sentiment in Washington as the reason behind the closure. But that may not be the whole truth.

Because the children were so persistent in running away from the institution, that kept the pupil turnover high enough to make it impossible for school officials to meet their alleged educational goals.

The resistance of students eventually marked not just the end of the boarding system in Rensselaer but all of Indiana.

'We Still Know So Little'

White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute closed when the Indian Aid withdrew funding in 1895. St. Joseph's Indian Normal School ceased operations one year later. Drexel Hall still stands across the street from the former St. Joseph's College.

Students in attendance at either school were sent to other institutions across the country when they closed. While 15 students returned to Yankton Agency, 26 to Pine Ridge Agency, and 10 children went to Quapaw, Cheyenne, Sac and Fox, and Kiowa agencies in Iowa, boarding school was not over for many children. Six children were sent to Carlisle, one to a boarding school in Santa Fe, and four to Hampton, Virginia.

The pain of going through the boarding school system is one that never left many students, including Zitkála-Šá. She returned to White's Institute to teach music, and went to Richmond's Earlham College upon her graduation in 1895.

She became the first Native American woman to compose an opera, and was a prolific voice for Native American civil rights throughout the turn of the century.

Singer produced a selection of Zitkála-Šá Sun Dance Opera in 2013 and 2015.

"She kind of transported these Yankton Dakota melodies into the opera itself. You know a miracle that we have writings from a Native American woman and they didn't get lost," Singer said.

She spoke out against the boarding school system her entire life, once writing that the "melancholy of those black days has left so long a shadow it darkens the path of years that have since gone by."

Decades after both institutions closed their doors though, the full extent of the shadow they left is unknown. Today, on the premises of White's Residential and Family Services, an aging cemetery a few dozen yards away from the main campus marks the final resting place of at least eight Native children. Some graves are unmarked.

Records show the following children died at White's Institute:

- Moses Two Bulls, 16, from Pine Ridge Reservation

- Rosa Fast Horse, 14, of Pine Ridge Reservation

- Reba White, 5, from Crow Creek Reservation

- Mary Trimmer, 12, from Santee Agency

- Carrie No Flesh, 13, from Pine Ridge Reservation

- Theresa Bissonette, around the age of 18, from Pine Ridge Reservation

- Siddie Long, 20-year-old from Wyandotte

While records indicate as many as 13 additional graves could be at that site. Some gravestones are unmarked, and one is marked with a letter "G."

13News also located four graves with the inscription "White's Institute" at Friend's Cemetery in Noble Township, but could not verify dates on the stones or names of the deceased.

These children died many hundreds of miles away from home. Rosa Fast Horse's father, Judge Fast Horse, reportedly lost his life in a desperate attempt to visit his child's grave.

Last summer, unmarked graves of 752 First Nations children in Canada prompted U.S. Department of the Interior Treasury Secretary Deb Haaland to launch an investigation which partially deals with how many more Native American Children are buried across the country. The department plans to release the results of that investigation in April 2022.

But St. Joseph's Indian Normal School and White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute were left out of that federal investigation, even though at least eight Native American children are buried in Wabash and at least two children reportedly died at St. Joseph's.

"It's not shocking that a school, or two schools in Indiana, have grave sites. My estimation is that virtually every school contracted by the federal government has a grave site," McBride said.

The Indiana Department of Natural Resources assembled a team of researchers to look into how many more children may be buried at both sites.

"We decided this was something that we could undertake. Looking for the names of children who went to school there and their tribal affiliation. So we're going to do some outreach and some communications with various tribal groups. It's kind of piecing these puzzles together," Director of Special Initiatives with DNR Jeannie Regan-Dinnius said.

The Indiana DNR is collaborating with teams at White's Residential and Family Services and researchers with the Jasper County Historical Society to investigate how many children could be buried there. The agency plans to conduct thorough research into both sites with the help of a company that conducts ground penetrating radar research.

"They'll come up with a potential map. And that'll give us an idea of the size and shape of the cemetery. It won't tell me who's buried in the cemetery, but it'll tell me, whether there's five graves or 10 graves or 50 graves. Then, that makes a difference of how we move forward," Regan-Dinnius said.

The DNR hopes to start that research by summer 2022. White's Residential Family Services said they would cooperate fully with work conducted on site by the Indiana Department of Natural Resource.

"The primary purposes of the project are to acknowledge the students there, identify the size/shape of the cemetery, restore the stones there, and reach out to the tribes affiliated to conduct outreach. We of course said that we were interested in the project," White's Residential & Family Services said in a statement to 13News.

White's Institute and St. Joseph's were far from the longest running, or largest residential schools in the United States. But if the religious groups and government organizations responsible for establishing them in Indiana aimed to mimic the larger residential schools like Carlisle, they succeeded when it comes to this most brutal variable.

"Many have passed idly through the Indian schools during the last decade, afterward to boast of their charity to the North American Indian. But few there are who have paused to question whether real life or long-lasting death lies beneath this semblance of civilization," Zitkála-Šá wrote in 1923.

Nearly a century after she wrote those words, as investigations into these institutions play out across the United States, it is becoming more clear which of those two circumstances is true.