BLOOMINGTON, Ind. — As news of Roe v. Wade's overturn flooded in, Ruth Mahaney remembered the stories.

There was the woman who leapt off the dining room table while her husband was at work, threw herself repeatedly against a hard floor, because she heard that was a good way to dislodge a pregnancy. Another woman fell pregnant with a religious leader’s baby and feared ostracization. One pair of roommates both secretly sought abortions and refused to tell a soul about their situation, even as they shared the same dorm room at Indiana University.

“They were both going through this at the same time. But neither one told each other. They were best friends. But they were so humiliated and shamed that they endured it alone," Mahaney said.

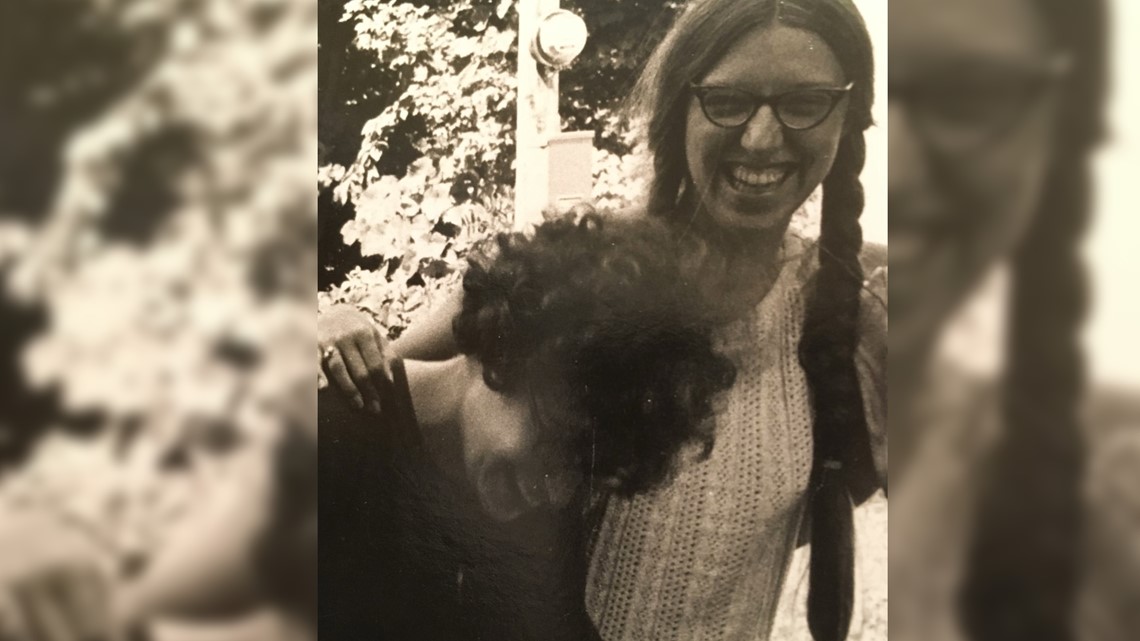

Those were all real situations Mahaney said she encountered as part of the Midwest Abortion Counseling Services group, an organization established on Indiana University’s campus that connected at least 100 women to abortion providers in the days before Roe v. Wade.

Mahaney worked as a counselor with the organization from 1968 to 1970.

“Abortion was a secret that nobody talked about it. And anybody who had had an abortion didn't talk about it. And the ways to get one were totally underground. Hidden. You had to hunt,” Mahaney said.

The efforts of clandestine groups like the Midwest Abortion Counseling Services helped women navigate an unregulated abortion market that did not always put their safety first, prior to the legalization of abortion granted by Roe v. Wade in 1973.

Until about the 1930s, women were able to access abortions through physicians, who largely worked out of unregulated independent practices. But beginning in the 'thirties and continuing into the 'forties, the federal government began pouring funds into building new hospitals.

When obstetricians and gynecologists moved into those spaces, they faced markedly more oversight from hospital administrators.

“There was a big clamp down to this thing that physicians had pretty much a lot of authority to perform. Suddenly, now they were under surveillance by hospital administrators. And it makes sense that these hospital administrators wanted to make sure that the people they employed were following the law, because these hospitals could have gotten in a lot of trouble,” said Dr. Karissa Haugeberg, who is an Assistant Professor of History at Tulane University in New Orleans and has traced the history of anti-abortion movements in her novel, Women Against Abortion: Inside The Largest Moral Reform Movement.

That new dynamic deterred many knowledgeable providers from continuing abortion services, even as demand persisted. According to estimates from the research group Guttmacher Institute, illegal abortions in the 1950s and 1960s ranged from 200,000 to 1.2 million per year.

The new gulf between people seeking abortions and providers willing to perform them created a black market for abortions by the late 1940s. While some physicians still performed abortions in secret, it was largely rogue abortionists or activist groups who stepped into physicians’ shoes.

"Women who had been accustomed to turning to their family physician, now their daughters could no longer do the same thing," Haugeberg said.

Those providers had varying degrees of repute. Some were indeed doctors who performed abortions at risk of losing their medical license, but others were self-taught, entrepreneurial sorts who were keen to leverage the inaccessibility of abortions as a pathway to extra cash.

"Because so many fewer physicians could practice this and, you know, exercise their own professional judgment, we see that underground market open up. And that's when we see this proliferation of nefarious providers," Haugeberg said.

In her research, Haugeberg found multiple instances when abortionists requested sexual favors in exchange for the price of a procedure, or cases when abortionists weren't forthright about the procedure's cost.

“Saying giving one number over the phone and then, when the woman arrives, saying that it's double the amount. And these women were so desperate that they weren't in a position to negotiate,” Haugeberg said.

RELATED: Chicago doctors seeing surge in out-of-state women with high-risk pregnancies seeking abortion care

It was organizations like The Midwest Abortion Counseling Services who helped women navigate through that maze of ill-intentioned providers, to ones who could provide a more safe abortion. In a college town like Bloomington, those connections could be crucial.

"So many college girls died, because they didn't know the landscape of the town that they went to. And then, immigrant women died at horrifically high rates too – probably because they didn't know who the safe people to turn to were," Haugeberg said.

Though the group certainly provided counseling and resources to college-aged women, most of the women who utilized the group's services were already mothers. Some women who contacted the group did so as the result of restricted access to birth control. At the time, doctors held full control over who had that access, and Mahaney recalled two male doctors affiliated with Indiana University created even more barriers. One woman, who contacted the group, had requested birth control from her doctor and was horrified by his response.

"Her doctor said, 'How many children do you have?' And she said, 'I have two'. And he said, 'Well, I like four. So after you have four, come back,'" Mahaney said.

That woman became pregnant within the year. Women also told counselors that one doctor was known to inquire the qualifications of a woman's partner before deciding whether or not to give them birth control.

"He would ask you about your young man. If you didn't know, or you hesitated, he decided that this was not a relationship he wanted to support, and he wouldn't give you birth control. So, totally in the hands of the doctors, whether you even got birth control," Mahaney said.

The organization hosted similar groups from across the Midwest on the third floor of Ballantine Hall, and helped other organizers access their network of providers, which extended across the country and at some points into Mexico.

They distributed flyers and information about their services across women's bathrooms in southern Indiana that read, Problem pregnancy? Call us, with a number that connected women straight to Mahaney.

"I went back to visit Bloomington a couple of years after I ended my time with [Midwest Abortion Counseling Services], and was introduced to somebody who said, 'Ruth Mahaney? Oh, it's a real person. That's the name that everybody looks up to get an abortion!' I had not even thought about disconnecting my phone before I left, but they continued to pay my bill," Mahaney said.

That phone number became essential, as did learning how to counsel women through it, because somehow, women living far from Indiana began reaching out for help.

"I know for a fact I counseled women from Texas, Colorado. From California to Utah. Kansas. We have such a large student population and they aren't all native to Indiana, that maybe went home and told friends," said Nancy Brand, one of the group's founders, in an interview with the Indiana University Bicentennial Oral History Project.

Though their services were in high-demand, it was risky work that opened up Mahaney and the 10 or so other women involved to arrest or prosecution.

Even as they distributed those flyers and hung stickers in bathroom stalls, they had to be discreet. If a woman did call their hotline, group protocol dictated they should not respond unless the woman specifically used the word abortion.

“Which sometimes was excruciating, because they would stutter and be so scared,” Mahaney said.

They would then ensure the woman wasn't being forced, or pressured into the abortion. From that point, the group would turn to their list of trusted abortion providers and walk a woman through her different options. Pricing was discussed, as was the advantage of each provider.

Most of the time, their next move was a call to Jane.

'Pregnant? Don't want to be? Call Jane'

Indiana's proximity to Chicago placed the Midwest Abortion Counseling Services in close proximity to one of the most prolific underground abortion networks in the country - The Jane Collective.

Unlike the Midwest Abortion Counseling Services, The Jane Collective trained staff to perform abortions themselves.

"Jane was really different because they were willing to be more open. And, I think they took more risks with that. So, they were one of our referrals," Mahaney said.

The Jane Collective provided abortions up until Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973. While the group is well-known today as The Jane Collective, that wasn't necessarily what members called themselves at the time.

"A sociologist made that up. We called ourselves The Abortion Counseling Service, or the service. And, technically, the name was The Abortion Counseling Service at the Chicago Women's Liberation Union. But, you know, people fall asleep by the time you say all that," said Sheila Avruch, who was a member of The Service when she was a college student at The University of Chicago.

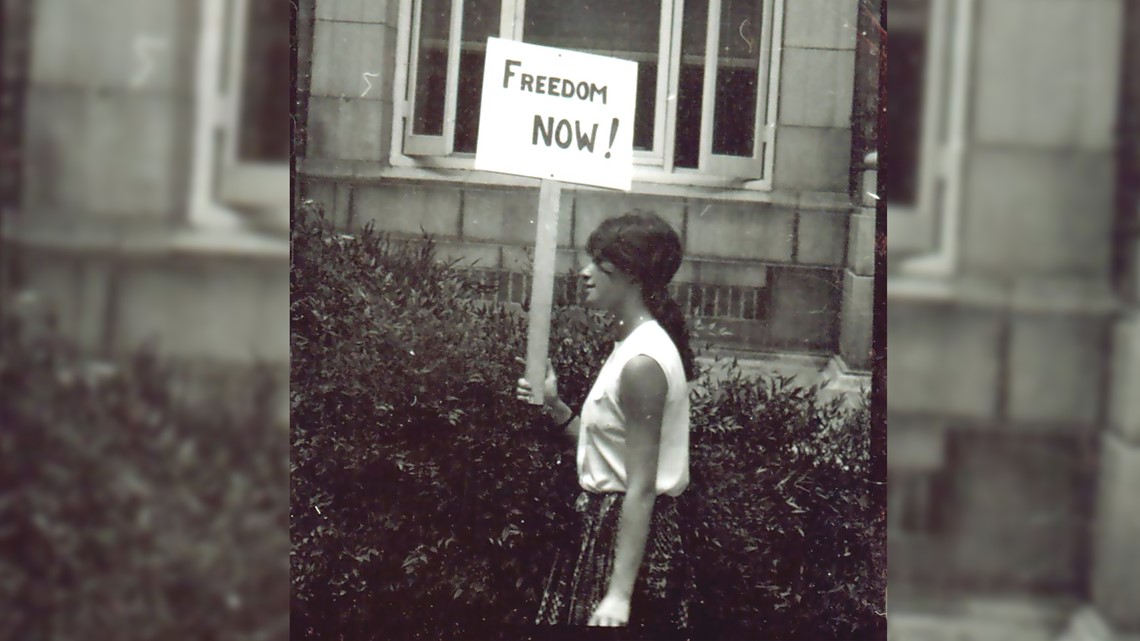

The Jane Collective began in Chicago when Heather Booth's friend confided to her that his sister was contemplating suicide due to an unwanted pregnancy. During a time when sex was rarely discussed, Booth hadn’t considered the particularities of abortion before. But she wanted to help.

"Simply as a good deed, try to help someone else who is really in need," Booth said.

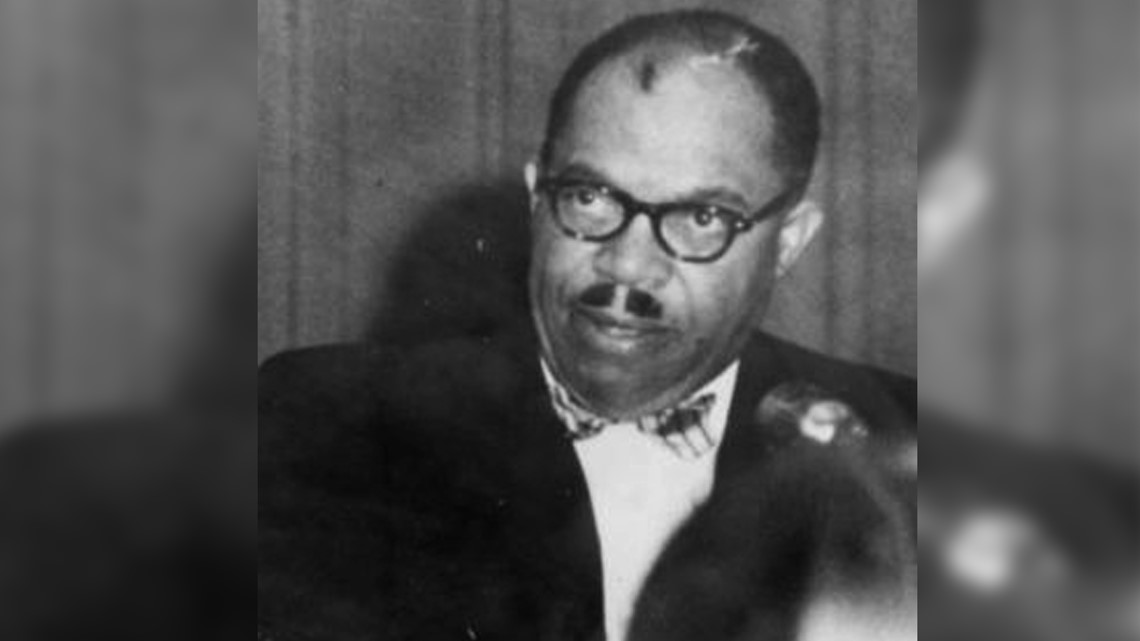

Booth was involved in the Civil Rights Movement at the time in Chicago, and called on Dr. T.R.M. Howard - a renowned civil rights activist whose name once appeared on a Ku Klux Klan death list for calling into an investigation into the murder of Emmitt Till - to help.

He was a leading provider of illegal abortions at the time, and considered that work to be a central piece to his civil rights work. Dr. Howard informed Booth what was involved with the procedure, what support women would need after, and what typical charges looked like.

“At some point a few years later, I lost track of Dr. Howard and I found out that he actually had been arrested for performing abortions. But, he didn't report me on it. It just shows what a courageous person he was,” Booth said.

By the time Booth had successfully procured the abortion for her friend's sister, word spread fast that she had access to a provider. Booth was fielding requests from dozens of women and felt compelled to help them all.

"It wasn't legal for three people to discuss preparing for an abortion in Chicago in 1965, or really before '73. We said, 'If you're pregnant, don't want to be? Call Jane,'" Booth said. It was a saying they plastered on flyers and spread through word of mouth.

As more women requested their services, Booth realized she would have to recruit other people. She connected with a physician called Mike who helped perform abortions until he eventually "grew bored" of the procedure and resigned.

When he quit, Mike revealed he had been harboring a secret - he had no medical degree. He was not a licensed physician at all.

"[Mike] said, 'Well, you guys can do it.' And they said, 'But we're not doctors.' And he said, 'Neither am I.' And it turned out that he was a med student," Mahaney said.

It sparked an epiphany for The Jane Collective. "They realized if Mike could do this, and it was safe, it was supportive of the women, they could do it.," Booth said.

Between 1969 and 1973, The Jane Collective went on to perform 11,000 abortions by Booth's estimate. At their height, the organization was servicing at least 100 women a day.

"We had basically two roles. And one was being an assistant, which you sort of started as an assistant, which involved a lot of hand holding, actually. And then you progressed to learning how to do an abortion," Avruch said.

Similarly to The Midwest Abortion Counseling Services, counselors within The Jane Collective helped women emotionally through the process of abortions. Avruch started off, like Mahaney had in Indiana, as a counselor.

"I was seeing poor women. Women who couldn't just hop on a plane - they didn't have any money. We were doing abortions for any amount of money they had at that point. And people were telling us they had $25, or they had $5. And we would do an abortion for them for $5. You couldn't fly to New York and get one done for $5," Avruch said.

For Hoosier women though, that's often what had to be done. Mahaney sometimes drove women to an airport in Bloomington, so they could take a flight to Chicago for the procedure.

It was the start of a grueling process. When the woman seeking an abortion arrived at a Chicago airport, she was picked up by a Jane and taken by car for tea or coffee. When they returned to the car, a blindfold was placed on the woman. She would be driven around the city, so she didn't know where she was.

“She was blindfolded the whole time, so that she could not identify anybody in court. If she was brought in to testify against the doctors or anybody helping, she couldn’t,” Mahaney said.

The car would then come to a stop outside of an empty office building or motel.

Once inside, the woman was instructed to lay on a sheet spread out on the floor, and to move as quickly as possible, in case authorities came to make an arrest. The blindfold remained on for the duration of the abortion.

“That was a good abortion in those days,” Mahaney said.

The Janes eventually implemented a new system that did away with the need for blindfolds, but it involved members putting their own identities at risk. A new, two-location system was established.

The Janes set up two apartments, one of which was called "The Front," that served as a waiting room. Family, friends, or significant others could support the woman throughout preparation for the abortion at that location. She was then taken to "The Place," a secondary location, where the abortions were actually performed.

"During that time, people weren't blindfolded. The workers were willing to take that risk, in order to ensure that there was support and caring for the people coming through for the abortions," Booth said.

Eventually, Avruch progressed from counselor to assistant, where she would actually have a tangible role throughout the abortions. But the very first day she stepped into that role, it all came crumbling down.

A woman confided to her sister-in-law that she sought an abortion from the service. Her sister-in-law then tipped off local authorities, who tracked them down to a high-rise apartment where a cohort of Janes stood prepped to perform the abortion.

Avruch recalled hearing a commotion in the hallway, and knew immediately they were in danger.

"We locked the door of the room we were in. And there was somebody who had taken off her clothes in the room, because she was going to get an abortion. And she put her clothes back on. We took our instruments. And then, I said let's throw them out the window," Avruch said.

Policemen kicked down the door.

"Apparently, they were just looking around for a man. They assumed a man was doing the abortions," Avruch said.

Eventually, Avruch was taken along with six other Janes to The Chicago Police Department on 11th and State. They were processed and placed in dark, dank cells with little room, or privacy. It was so crowded, Avruch sat on the floor.

"There were people screaming and yelling all night. There were people coming down, probably, from drugs. A lot of screaming, a lot of banging, a lot of people screaming at the people who were screaming," Avruch said.

The group was eventually charged and indicted. In total, Avruch estimates the seven women faced a total of 711 charges between them, for abortion and conspiracy to commit abortion. Each one of the charges was a felony that carried a 10-year sentence.

"I was about to graduate from college, I felt like I was, ready to fly out into the world. And I didn't particularly want to spend my 20s and 30s caged," Avruch said.

The women were bailed out of prison by The Jane Collective, but they still faced those charges. As they awaited their trial date, their attorney, Joanne Wolfson, watched the Roe v. Wade case percolate in the Supreme Court and came up with a plan.

"Very smart, interesting woman. She was following what was going on with the Supreme Court on this issue. And she felt that the appropriate technique for us was just to keep having reasonable motions that might lead to a little bit of delay, sort of string the whole thing out to see what the Supreme Court would do," Avruch said.

Wolfson was right. In 1973, the Supreme Court decided a woman's right to an abortion was constitutional through Roe v. Wade. Avruch, and the other Janes, were released from prison.

"We were very happy about Roe v. Wade. I feel like I have a very personal feeling about that law, apart from the fact that it recognized that women have a fundamental right to their own bodies. I think it was very personal for me," Avruch said.

The Jane Collective disbanded immediately in Chicago. Back in Bloomington, the IU’s Women’s Liberation Movement established a Women’s Crisis Service to provide Bloomington area women support in situations such as rape, divorce, and abortion, and also in areas such as legal problems, day care, and minority women concerns.

The Crisis Service operated out of the Women’s Center, and the women also established a rape crisis center which would go on to become Bloomington’s Middle Way House.

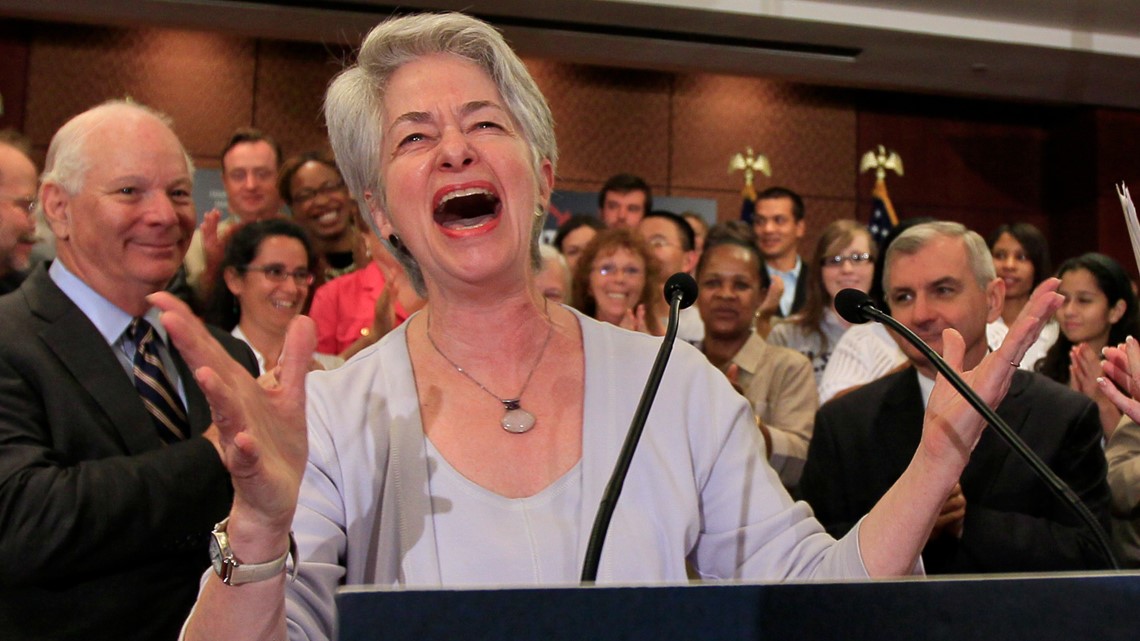

The activists who performed abortions or provided access to them soon turned their attentions elsewhere, as doctors stepped back into the roles they had once filled decades before. Mahaney moved to San Francisco, and became a prolific voice for LGBTQ+ rights. Avruch turned her attention to the welfare and rights of children. Booth became a prominent community organizer and activist.

"I think, "it's abortion," is never an easy decision. And I think, for all of the women, it was a painful experience. And you know, it was a fact that it was such a shaming experience in many ways that this variety was making it so difficult. And something to be so ashamed of has an impact. I think it's, it has had a huge impact on many women's lives," Mahaney said.