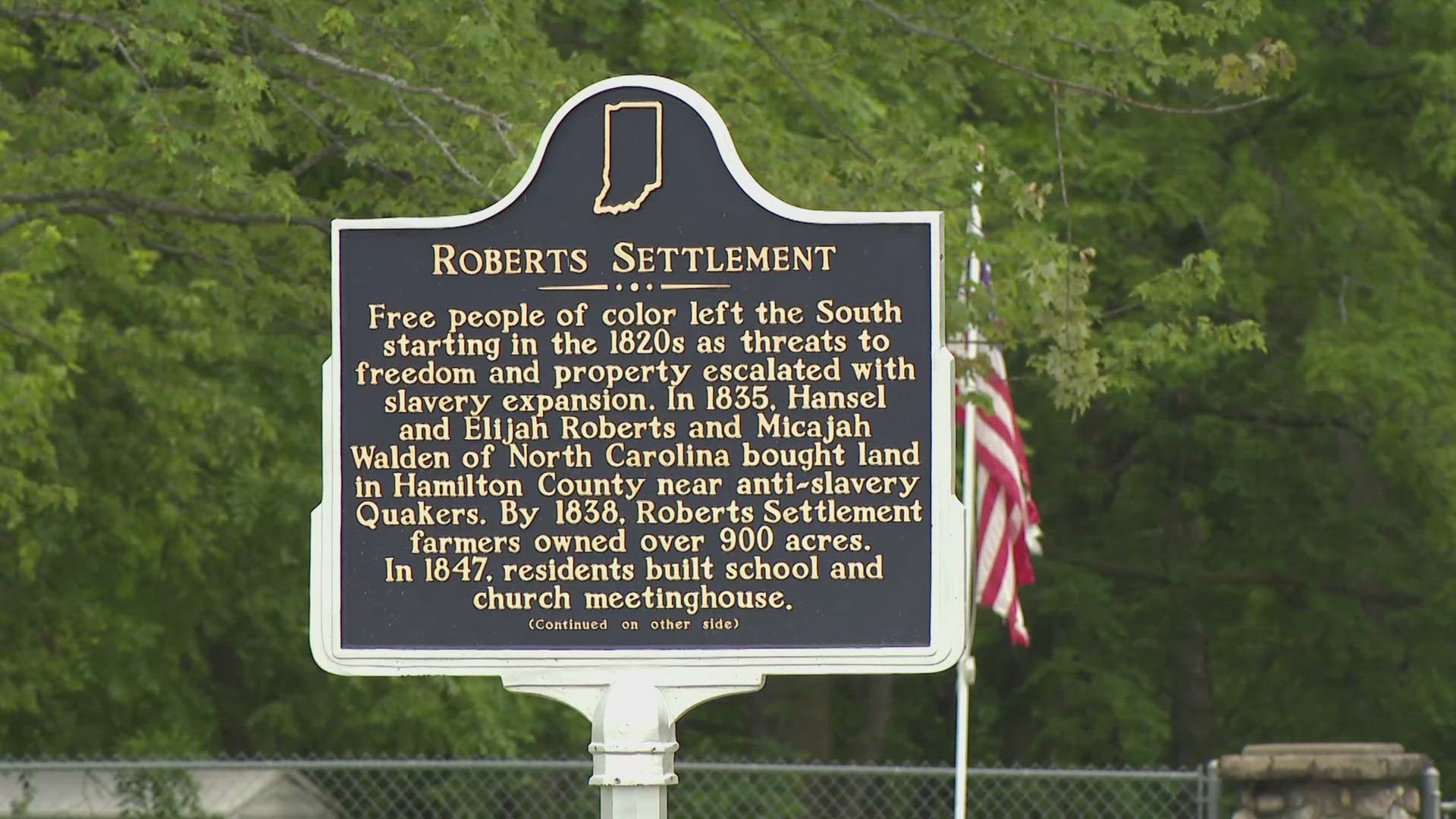

ATLANTA, Ind. — In a rural part of northern Hamilton County is a part of history connected to the Juneteenth holiday.

"Roberts Settlement was a community — a settlement of free people of color," said Bryan Glover, a descendent of Roberts Settlement.

According to Glover, free people of color needs some explaining when it comes to the terminology of the 1700s and 1800s.

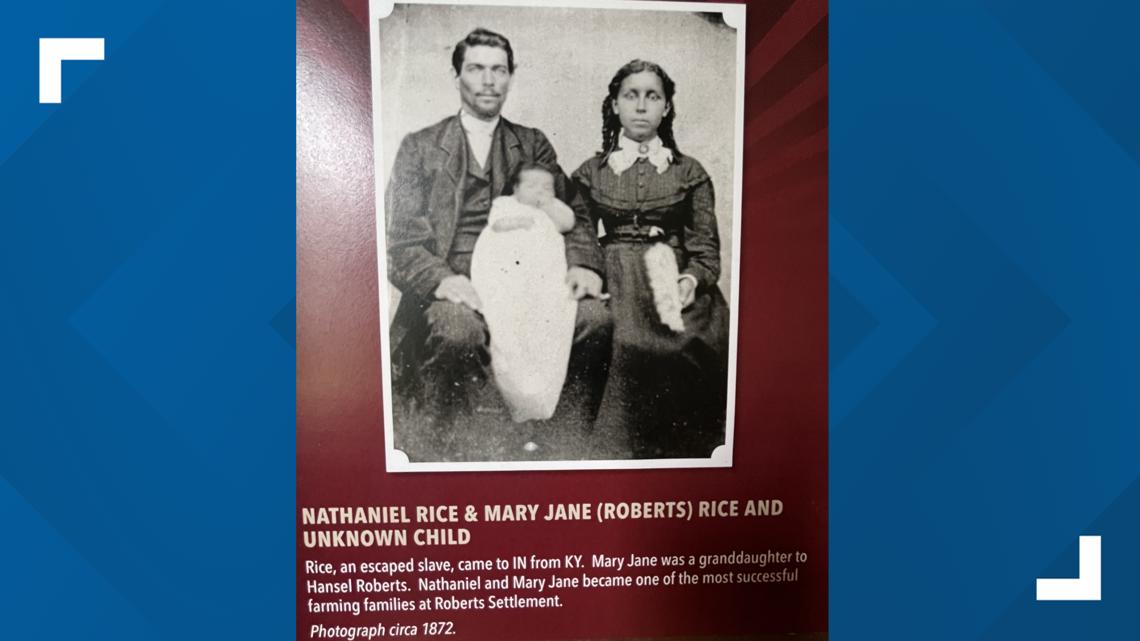

"These would have been people who were free, as far back as we know. Because in Colonial America, Colonial Virginia, your freedom was determined by your mother's status. If your mother was free, you were free," Glover said. "These were children of usually indentured white women — European, probably English, Irish, Scottish women, and enslaved Black men who had families together. Then, over time, those people migrated. Since the mother was free, the children were free."

Glover said those families, over time, migrated from Virginia to the frontier areas of North Carolina, where they had a little more autonomy because in Virginia, they were tightening the rules on free people of color. North Carolina was like a safe haven for these families.

From there, Glover said the families moved to areas where Native American tribes were living in the coastal plains area.

"The Meherrins, the Saponi and many of them intermarried with these Native American families in that area," Glover said. "So, at this point, they took on this triracial character, if you will. They were still identified as free people of color."

"As time marched on, as we got closer to the period of civil unrest in the 1830s to the Civil War, their rights were being taken away from them. That's when they began their exodus out of North Carolina and coming to what was then the newly formed states of Ohio and Indiana, the old northwest territory, where slavery had been outlawed," Glover said. "They found freedom and hope here. They settled in various communities. We are a community of these immigrants who came from North Carolina seeking freedom and liberty from the tyranny in the South."

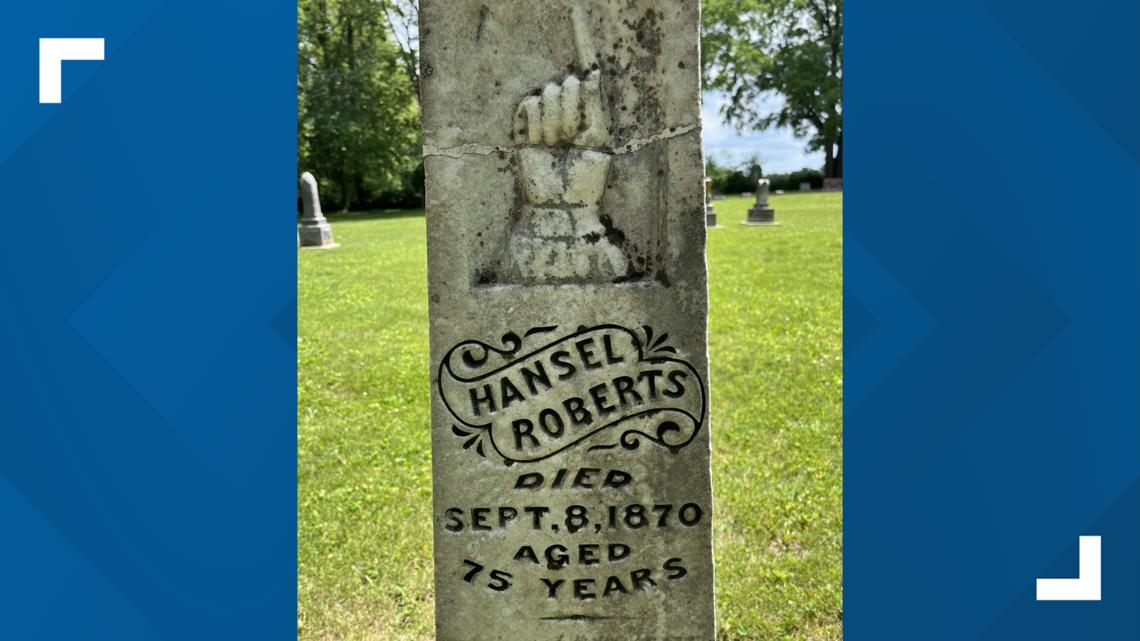

They migrated to Indiana from the South, owning 1,700 acres of land acquired directly from the federal government.

"They were able to enjoy the successes and fruits of their labor as farmers. But, as we got close to 1850, Indiana instituted a new constitution – Article 13 – that banned the migration Indiana of negroes and mulattos as the way it was framed in Article 13," Glover said.

According to Glover, free people of color lived in an area surrounded by Quakers and Wesleyan Methodists, and they worked in the land and worshipped together.

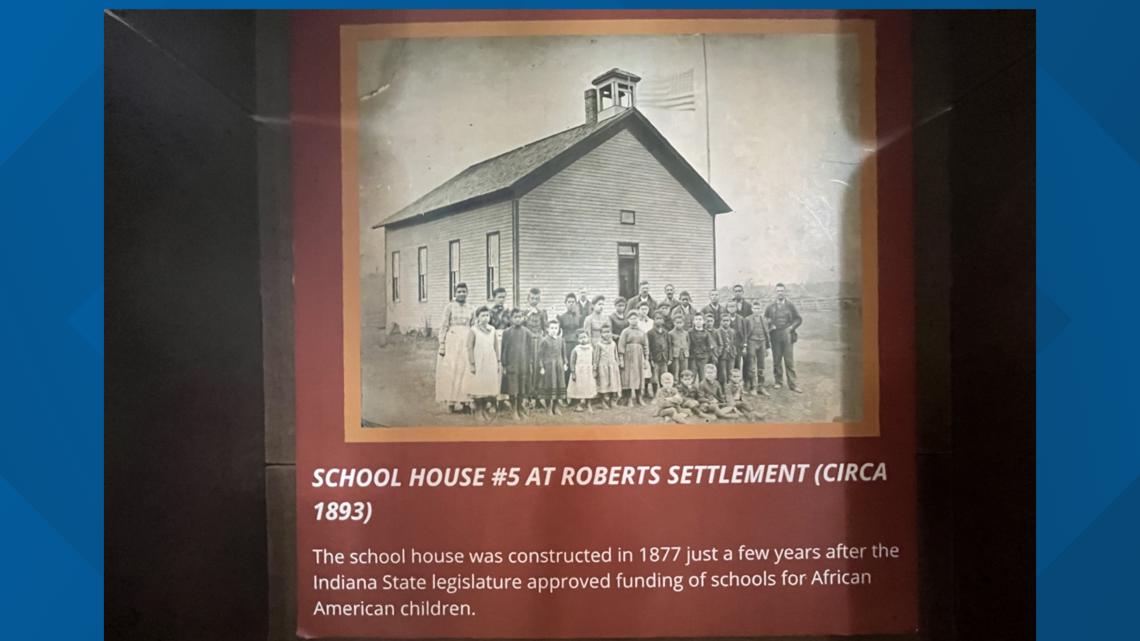

"They found freedom and hope here," Glover said. "They were able to build their own schools, build their own church, worship as they wished to worship."

Some of the men buried in this cemetery served alongside Union troops in 1865 and traveled to liberate enslaved people in Texas.

"Juneteenth is freedom day in Texas. Texas was the last state to finally get the memo that slavery had ended," Glover said. "Some of our Roberts ancestors who served in the Civil War USCT 28th regiment also went on that expedition. We don't know what their role was – it's hard to know what anybody's role was – but we'd like to believe they were part of that liberation."

"I believe the people at Roberts Settlement, the men who went off to serve in the Civil War, they saw it as an opportunity that if slavery is ended, this is good for us, too," Glover said. "Even though we have our freedom, we will be accepted, we will be able to participate politically, socially and in all ways."

Glover described what life was like around the time of Juneteenth.

"Around the time of Juneteenth in 1865, Roberts Settlement is kind of approaching it's golden era. Farm prices are high, there's a need for goods being produced on these farms, and the Roberts farmers are starting to be successful," Glover said. "They've cleared their land. They were able to get their crops and animals to markets. They were starting to realize the financial benefits of that. So, things economically are good. Yet, there were still issues in the greater society of that acceptance."

Glover described what life was like at Roberts Settlement after Juneteenth.

"They had their freedoms. They had been free for generations going back into the 17th century. They had known what it meant to be free. They had educated themselves. They had produced doctors, lawyers, teachers, preachers, so they were living this American dream in some ways," Glover said. "For them, in many ways, life would continue on. But inside, they believed that now we will be accepted like everyone else in the community and everywhere else, and we won't need to worry about the color of our skin."

Glover said people in the Roberts Settlement continued to face challenges.

"People knew this was a community of free people of color, [yet] there was still discrimination. I think they believed this would all change as a result of the end of the civil strife," Glover said. "The community began to decline in the 1890s. No cheap farmland available at that point. Younger generations had the benefit of their education. Like today, they went off to other places. These were folks who were trained as doctors, lawyers, teachers. They went into other communities of Blacks that migrated into other northern cities like St. Louis, Chicago, and they became some of the leaders in those communities in terms of bringing these services and bringing education to these new arrivals."

According to Glover, there were approximately 75 people still living at Roberts Settlement by 1920.

"It was sort of the beginning of the end of this place as a community where people lived," Glover said.

Every July, descendants of Roberts Settlement come back to the property for homecomings. Their next homecoming is July 6, 2024, with a chance to reconnect and learn about their legacy.

Now, there is an effort to restore the chapel.

"It's starting to show its signs of deterioration. This chapel was built in 1858. The last active congregation was in the 1950s. There were still a few people attending church here. But, it's been hard to keep it up," Glover said. "We need to maintain it. We're determined that we're going to do it. It means a lot to me to see us again preserve the places, the grounds that our ancestors walked on, the places where they sat, the places where they worshipped."

Glover is helping to launch a legacy walk on the property to educate people about their history.

"We all want to believe that our ancestors are smiling down as they look upon what we're doing," Glover said. "They probably didn't think that anything they did merited this kind of recognition. They were guided by their faith. They were guided by their values. I don't know if they thought was they were doing was special. They were doing what they thought they were supposed to do. I think they would say, 'My, we did all that,'" Glover said.

"My mother always said, 'You need to know where you come from,'" Glover said. "'You didn't just come from this town you grew up in. You come from generations of people.'"

Glover is helping history live on and inspire generations to come.

"There's so much we can learn from history. We can learn from the people of Roberts Settlement. Some of the things they experienced 150 years ago, we're going through that today," Glover said.

Glover reflected on what Juneteenth means to him.

"Juneteenth is important to me just because I believe our freedom is a natural right," Glover said. "No man can own another man. It's important that everybody be able to have that freedom and be able to express themselves, live out their desire, their potential. It's something as basic as that."

Glover is passionate about the Roberts Settlement property and the people who settled there.

"I can't imagine what it was like at that time being a Black person in America, having opportunity denied," Glover said. "But, I really appreciate the strength and fortitude that these people had — that no matter what, they were going to find a way. They were going to make a way."