INDIANAPOLIS (WTHR) - Jerry Harkness is going through the media car wash. Here comes WTHR on a gloomy Wednesday afternoon, but before sitting down in the basement of his north Indianapolis home, Harkness has to field calls from Sports Illustrated and from a producer for former Georgetown head coach and current analyst John Thompson. After we are done, the Indianapolis Star will arrive with a reporter and a photographer in tow. One after another after another…

“I’ve done about 40-45 interviews this week,’’ Harkness said with a smile. He will be a popular man in San Antonio this week, doing TV and radio work. “This is more media than when we actually had when won the national title. I’m almost as popular as Sister Jean. But not quite.’’

This is a moment in the sun that the 77-year-old Harkness never could have expected – “not while I’m on this side of the ground,’’ he said with a laugh. He was the captain of the 1963 Loyola Ramblers team that beat Mississippi State in the regional semifinal in what later was called “The Game of Change" (and more on that later). He also went on to play professionally for Knicks and the Pacers, then became the first black TV sports anchor (for WTHR, by the way) while remaining a committed trailblazer for civil rights and racial unity.

Everybody is calling, though, because…you know why:

Loyola.

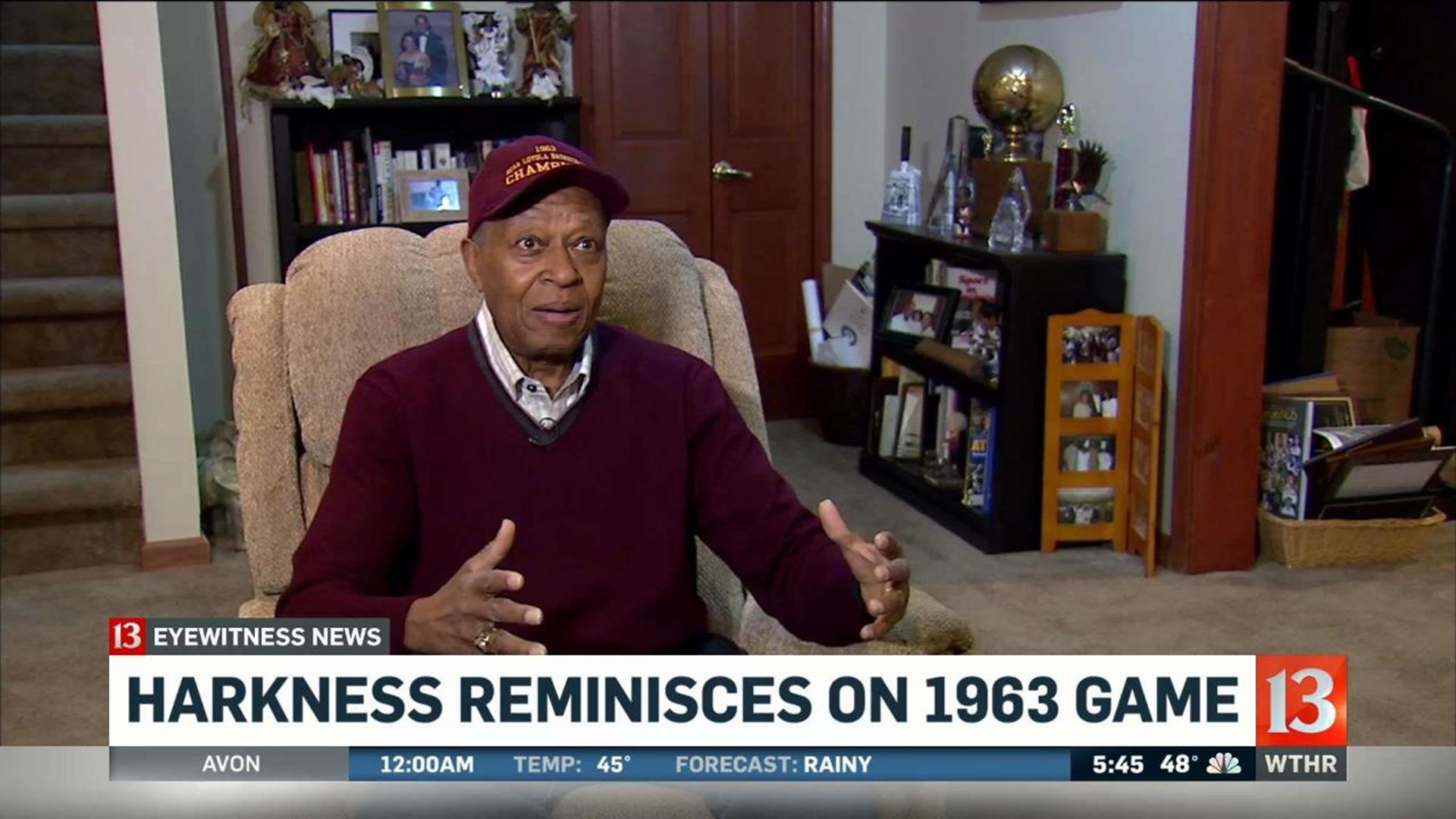

The Ramblers, the ultimate tournament Cinderella, have earned their way into the Final Four in San Antonio, where they will take on Michigan in one semifinal Saturday. Fifty-five years after the 1963 run to glory, Harkness is in great demand, and now he is sitting in his finished basement, surrounded by a lifetime worth of mementos, yelling upstairs to his wife, Sarah, to bring him his 1963 Loyola hat.

“Can’t do interviews without my hat,’’ he said.

Just as this year’s Ramblers are writing a made-for-celluloid story in this year’s upside-down NCAA Tournament, so did the 1963 team. It’s not that Harkness’ team came out of nowhere – they were a top team in the country that entire season – but that tournament run, and the game against Mississippi State, offered a story that was every bit as compelling – more socially important, really – than Sister Jean’s inspiring 2018 team.

“I’m really enjoying all of this,’’ Harkness said as he put on the Loyola hat and prepared for his TV closeup. “How often do you get to tell the story?’’

This is the story, or at least part of it.

* * *

There are photos of Harkness at the White House with former President Barack Obama. There are awards scattered throughout the room. All of them mean something important to Harkness, but there’s one poster that means the most, one that he gazes upon with an exalted sense of pride.

It’s a photo of Harkness, a black man, shaking hands at midcourt with Joe Dan Gold, a white man who was a member of the all-white Mississippi State team that Loyola faced in the regional semifinal. The headline reads, “The Game of Change.’’

In the years prior to 1963, Mississippi State had refused to play in the NCAA Tournament if it meant playing against integrated basketball teams. The Mississippi governor had run on a platform of segregation, and Jim Crow was still the rule in the Deep South. Now, though, in 1963, the school president and the head coach wanted to play in the tournament, even if it meant running afoul of the governor.

The state of Mississippi was prepared to serve an injunction to stop the basketball team from going up north and playing in the tournament against integrated teams, but Mississippi State’s president and basketball coach had other ideas: One man escaped to Nashville, the other to Memphis, figuring if the state couldn’t find them, they couldn’t serve an injunction. The team itself made a quick getaway from Starkville, and Mississippi State was in the NCAA Tournament. Playing integrated teams. Playing Loyola in the regional semifinal in East Lansing, Mich.

Before the game, Harkness and Mississippi State’s Joe Dan Gold, the two teams’ captains, met at center court to get final instructions from the referee. They shook hands. And the country changed, if just subtly.

“Did you have any idea at the time what that moment meant?’’ Harkness was asked.

“No idea,’’ he said. “We found out they went through a lot to be there, so that made me feel a closeness to them. I went up and looked [Gold] in the face and I smiled. Now, he didn’t smile; he had his game face on. But I could see he was glad to be there and didn’t have racial problems. I’ll never forget the flashbulbs popping – pop, pop, pop – all over the place and I was stunned. And I knew, this is more than a game. This is history. I’ll never forget that.’’

Understand, just three months earlier, James Meredith, a black man, integrated the University of Mississippi under a hailstorm of protest and violence. But two years after the game, another black man named James Holmes integrated Mississippi State without anything approaching the level of turbulence Ole Miss experienced earlier.

“You see what sports can do,’’ Harkness said.

Most of the country knows about the all-black Texas Western team that beat Adolph Rupp and the all-white Kentucky team in the 1966 final, largely due to the popularity of a book and a movie called “Glory Road.’’ But Harkness, Loyola and Mississippi State blazed the trail to racial inclusion three years earlier. It was a similar story, but it was different in several ways, too. Harkness’ and Loyola’s story have been told in a documentary that was directed by Harkness’ son, Jerald, but just as “Hoosiers’’ brought the Milan story into the mainstream, it’s the ’66 “Glory Road’’ team that gets most of the publicity.

Until this week.

Now we’re all learning more about “The Game of Change.’’

Good thing.

I wondered why the Texas Western game against Kentucky got all the publicity in later years while the Loyola-Mississippi State game was something of a historical footnote.

“When you want to sell movies…they want the clash between the all-black team versus the all-white team and they can battle against each other,’’ Harkness said. “Our story was about blacks and whites coming together to bring change. They want the bad guy, being Rupp. Wouldn’t it be nice if you show a black team and a white team coming together, and then later in life, the families all getting close? When we were in Atlanta, Joe Dan Gold’s brother sat with us and we all went out together after the game. We’ve all gotten to know one another and our families have spent time together. That’s our story, a better story, but sometimes in the media, we lean toward [racial conflict].’’

Loyola would go on to win that game against Mississippi State, then knocked off Illinois and Duke before eventually winning the title with an overtime victory over Cincinnati.

“That game [against Mississippi State] is the greatest athletic event I’ve been involved in in my life,’’ Harkness said. “You get a winner in the NCAA Tournament every year, but you don’t get a friendship and a closeness with guys [from Mississippi State] and you make changes in America.’’

For all that Mississippi State went through, it was equally difficult for Loyola, a team dominated by African-Americans at a time when being black in America meant discrimination at every turn. During the season, Ramblers players had coins tossed at them, were denied access to hotels and restaurants across the country, were pelted with the n-word at various stops along the road. After Loyola crushed Tennessee Tech in the NCAA Tournament opener, Harkness and his teammates returned to campus and found ugly letters addressed to their dorms. The KKK and other racists had a message: Watch your backs.

The pressure on Loyola came from everywhere, including fellow African-Americans. These were the early days of the Civil Rights Movement, and Loyola, a team that started several black players, were hearing, “We’re counting on you. It’s important for you to win for the cause.’’

Loyola won for the cause, but more, they won for themselves and their school.

There is no deep social undercurrent to this year’s unlikely Loyola run, but the Ramblers, just like the Butler Bulldogs in 2010 and 2011, have captured the imagination of the country.

“I go back to earlier this year, all the [1963] guys were invited to watch them practice, and the first thing I noticed is they were laughing and enjoying themselves,’’ Harkness said. “And then I saw the talent and I said, 'Wow, it's better than we've had in a long time.' I could see that right away. Then we went down to eat and they showed [a video of] the ’63 team and they were oohing and aahing, and they came over and asked questions. I thought, 'There's something special about these guys.' They were really warm and gentle and wanted to know what it was like to be in the Final Four and to win it. I just felt a part of them, like family."

Harkness marvels at Loyola’s players, their shooting ability, their fundamentals, their willingness and ability to pass the ball. Yes, he said, they can beat Michigan. And then, who knows…?

"They don’t look like they’ve got a lot of talent," he said, "but they’ve got a lot of talent in every area and in passing, they’re superb."

All those years later, the kid who grew up poor in Harlem, the kid who was moved to try out for the varsity his senior year of high school after meeting Jackie Robinson, is surrounded by the mementos of a life well-lived. And with Loyola in the Final Four, and his friend Sister Jean offering her support and prayers, he has yet another memory that will last a lifetime.

Want more Kravitz? Subscribe to The Bob Kravitz Podcast on iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher or TuneIn. If you have a good story idea that's worth writing, feel free to send it to bkravitz@wthr.com.