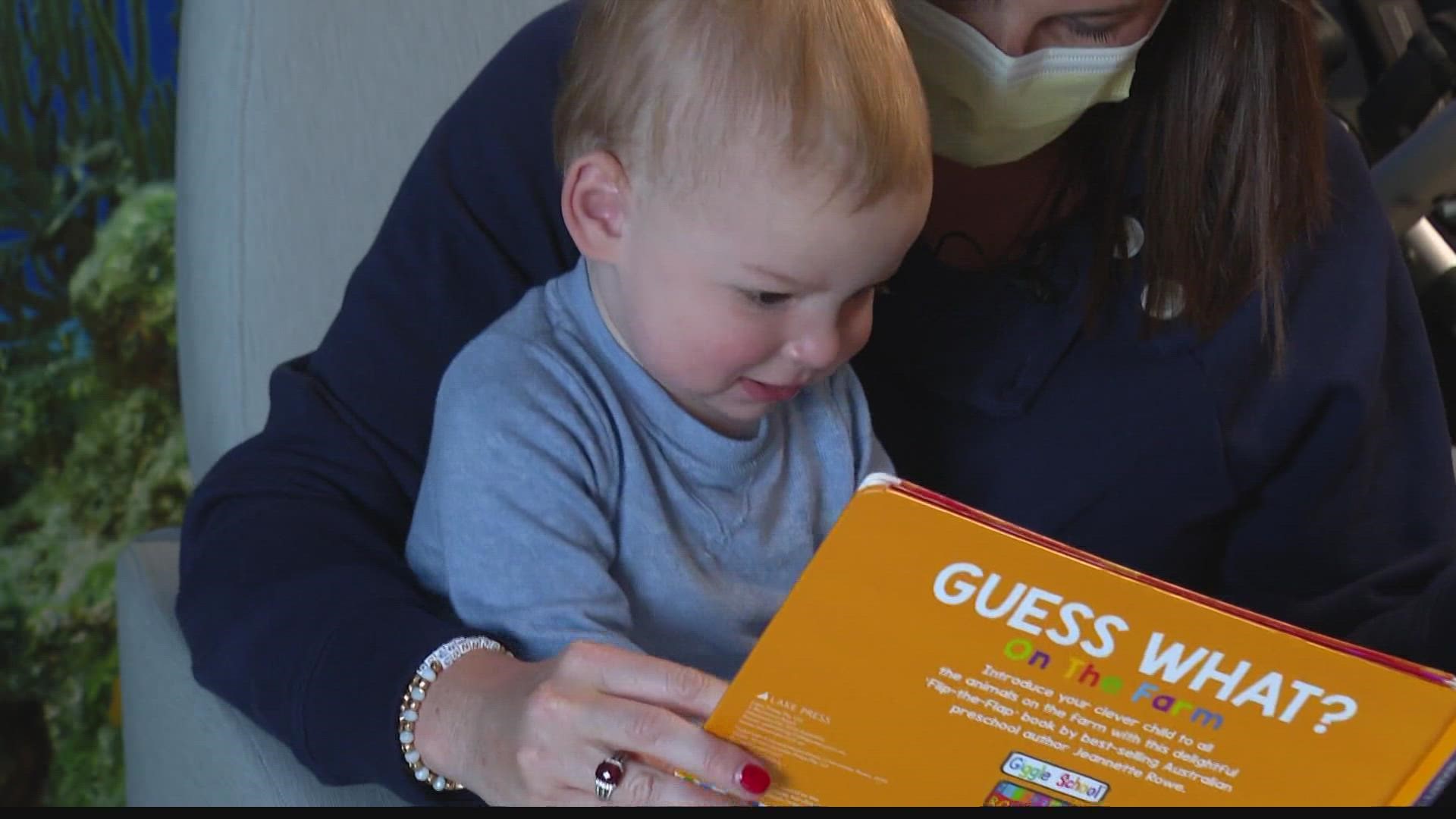

CARMEL, Ind. — Every Thursday, 1-year-old Grant and his parents come to IU Health North Hospital so he can receive a five-hour enzyme replacement infusion.

It’s something they’ve been doing since he was about four weeks old.

“It’s kind of become part of our life and what we do every week,” said Alison Breitbarth, Grant’s mom.

In February 2021, Grant’s newborn screening was flagged after it showed signs of infantile onset Pompe disease, a rare genetic condition that can affect the heart and muscles.

Breitbarth was barely home from the hospital when she received the call.

“The words were completely foreign to me as she was saying Pompe on the phone. I had no idea what she was talking about,” Breitbarth said. “It was a lot to take in and it was really hard for several months.”

At the time, it didn’t make sense since Grant wasn’t showing any symptoms or acting different.

“He seemed completely fine and completely healthy. He was being your typical baby,” she said.

If the disease is not detected early, it can lead to death or heart failure within the first year of life. Thankfully in Grant’s case, the newborn screening spotted it before any symptoms could develop.

The Breitbarth family also learned the condition could be treated and screens on Grant’s heart looked normal.

“[His heart] was completely normal, and I remember the doctor saying, ‘Count this as a win. This is huge.’ At the time, I had no idea that it was such a big deal,” Breitbarth said.

Grant was the first baby in Indiana to be diagnosed with Pompe disease through a newborn screening.

The condition is detected through a heel stick, where doctors take a sample of blood from the baby. It’s then sent to a lab to be analyzed for more than 50 rare, life-threatening genetic conditions.

Right now, newborn screening for Pompe disease is only required in about 30 states, according to NewSTEPs.

Just seven months before Grant was born, Indiana passed legislation to start screening babies for this condition. The bill also added Hurler syndrome and Krabbe disease to the 49 other disorders already on the screening panel.

It was inspired by Bryce Clausen, who was diagnosed with Krabbe Disease as a baby. Since he wasn’t tested early enough, he sadly died at 14 months old — just days after the bill was signed.

Since then, two babies at IU Health were diagnosed with “Infantile Onset Pompe Disease,” including Grant. They’ve also detected about 15 other babies with late onset Pompe disease.

“I think about it a lot that if our 4-year-old had Pompe, we would’ve been severely impacted by it because it was not on newborn screening when he was born,” Breitbarth said. “I feel like babies shouldn’t have to get lucky and live somewhere that screens for it. It should be something that is done for everybody.”

Throughout Grant’s journey, Katie Sapp has helped the family navigate questions and concerns. She is an IU Health genetic counselor who works specifically with kids that have metabolic conditions — with most of them coming from newborn screenings.

“My job is to kind of help families recognize where Pompe used to be and where Pompe is now with newborn screening and help field all those questions that inevitably come,” Sapp said.

She works with patients sometimes from birth until later in their life and also advocate for their care.

“We talk through the symptoms, the genetics and inheritance of it, how we test for it, coordinating genetic testing, explaining genetic test results and then talking about long-term management and prognosis,” she said.

She said there are two different forms of Pompe disease. The first one is “infantile onset.” That’s when babies develop heart issues and significant muscle weakness. It can be treated to help improve damage to the heart but not the muscle.

There’s also “late onset,” where someone can develop symptoms during their first year or during adulthood. For this condition, people usually don’t have heart issues.

“Once the symptoms start, we are essentially working from behind so we know damage already happened to muscles at that point and we can’t reverse that damage,” Sapp said.

That’s why Sapp said it is so important that newborn screenings include Pompe disease so doctors can catch it early.

“Getting a newborn screening diagnosis is absolutely life-changing. I would never try to minimize that for anyone, but it doesn’t have to be life limiting and that’s what our job is to work with families to prevent serious complications of a newborn screening diagnosis,” she said.

For now, Grant will continue to receive a weekly infusion for the rest of his life, but Sapp said there is a lot of research and development on the horizon for the condition.

In the meantime, Grant’s family is enjoying his energic personality as they try and take things one day at a time.

“You would never know that he had Pompe unless I told you. He is doing great. He is meeting all of his milestones. There isn’t anything that he doesn’t love to climb,” Breitbarth said. “He’s your typical, wild 1-year-old and we are so thankful for that.”